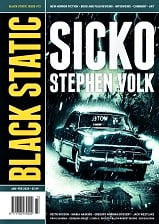

Black Static #73, January/February 2020

Black Static #73, January/February 2020

“Sicko” by Stephen Volk

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

The latest issue of this British magazine of horror fiction offers a novelette that takes a new look at a familiar classic, and four short stories of people facing frightening disasters.

From the very beginning, “Sicko” by Stephen Volk is obviously a variation on Psycho, particularly the Alfred Hitchcock film rather than the original novel by Robert Bloch. It starts with the protagonist in the shower of a motel room, remembering how she stole a large amount of money from her employer. Instead of dying at the hands of a lunatic, however, she returns to her workplace, intending to return the cash. She soon learns that not all human monsters are insane, and finds the inner strength to escape them.

The first part of the story follows the plot of the movie closely, adding a great deal of insight into the psychology of the main character. Just when the reader expects the whole thing to be a rehash of the original, albeit a highly skilled one, it goes in an unexpected direction, as disturbing as its model, but in a completely different way. Although the protagonist suffers greatly, she is no longer a helpless victim, and survives a terrible experience with her dignity intact.

Reimagining an icon of cinematic terror, which has already been imitated and parodied countless times, is an act of great daring. Fortunately, the author has the talent to pull it off successfully.

“You Are My Sunshine” by Keith Rosson takes place aboard a cruise ship that carries children who are at risk of suffering from various traumas. A trio of rock musicians are aboard to provide entertainment. During the voyage, giant monsters appear on Earth from nowhere. Unable to land because of the ravages of the huge creatures, the ship remains at sea. Those aboard face the possibility of starvation once their supplies run out.

Much of the plot deals with tensions among the musicians. The characters, although mostly unpleasant, are believable. The setting is an unusual and convincing one. The same is not true for the monsters, which seem to come from another kind of story entirely.

“Cleaver, Meat, and Block” by Maria Haskins takes place after a plague caused those infected to go on a rampage, killing and eating people in a frenzy. After the disease is under control, those who murdered and devoured their victims seem to have no memories of their crimes, and go on to live relatively normal lives. The main character is a teenage girl who lost her family to the insane cannibals, and who barely escaped with her life. She now lives with her grandparents, and works in their butcher shop. A boy her own age, who was one of the infected maniacs who killed her relatives, follows her home after school each day, leading to a final confrontation.

This gruesome tale, which seems to owe something to Night of the Living Dead, offers few surprises, although the author writes quite well. We learn that the girl can wield a meat cleaver in the first sentence, so the scene of bloody violence at the end of the story is predictable from the start.

The disaster at the heart of “We Didn’t Always Live in the Woods” by Jack Westlake is a much more intimate one, shared by only two people. A man discovers that his wife had an affair. Their estrangement parallels a bizarre phenomenon, in which the trees surrounding their house draw ever nearer, eventually invading their home.

At first, the premise is a unique and effective metaphor for the slow dissolving of a relationship. Later, however, a being who is half-human and half-tree shows up, lessening the story’s allegorical power by making it too literal.

In “The Hearts of All” by Gregory Norman Bossert, a drug abuser and a real estate agent wander through an area devastated by fire. An injured horse accompanies them on their journey past the ruins of suburban homes. Following a dog into what little remains of the home of its owners, the drug user makes a strange discovery. Buried under the ashes is what seems to be a glass sculpture, containing the mingled faces and body parts of a family.

This is a surreal, dream-like story, with no explanation for the weird glassy object. If it is intended to be a symbol, its meaning is far from clear.

Victoria Silverwolf thinks Psycho is the greatest non-supernatural horror film of all time, and that the novel is quite good as well.