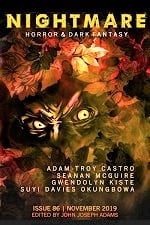

Nightmare Magazine #86, November 2019

Nightmare Magazine #86, November 2019

“Dollhouse” by Adam-Troy Castro

Reviewed by Tara Grímravn

This month, the editor at Nightmare Magazine has chosen a rather odd set of original stories to grace their 86th issue. In these two tales, we’ll be visiting a rather odd assortment of toys in a little girl’s room before getting an interesting look at the diary of one of Dracula’s victims.

“Dollhouse” by Adam-Troy Castro

I’d like to start this review by saying that I am not entirely certain how best to summarize Castro’s story. No matter how I approach it, I end up including some form of a spoiler, which I would prefer to avoid. To that end, what I will say is that the story is about three toys found in a little girl’s room. Each one is inhabited—not by spirits, but by people—yet only one remembers any details of who they are or why they’re there.

Castro’s story is genuinely unsettling. Of course, readers won’t find the usual monsters here that one might expect. It’s all about the circumstances in which these three people find themselves and the imagery that the author uses to describe their predicament, more than anything else. It reads like something straight out of a serial killer’s diary, only without anyone actually dying (although I think that’d be preferable to what these people are forced to endure). To say more than this would ruin the fun.

“The Eight People Who Murdered Me (Excerpt from Lucy Westenra’s Diary)” by Gwendolyn Kiste

Lucy Westenra has had her run-in with Dracula. Now, having succumbed to his curse, she writes in her diary and chastises every person she knows in turn. Beginning with Dracula, the cause of her ailment, she moves down the line to her mother, then Mina, Dr. Van Helsing, the mob who broke into her tomb, and finally Dracula again.

I was quite looking forward to Kiste’s tale, being an avid fan of Bram Stoker’s original book. Unfortunately, I’m not at all impressed with this story. It isn’t even remotely faithful to the actual character of Lucy Westenra from Bram Stoker’s Dracula. True, Lucy was a lively, willful, flirtatious girl but she was still very much a product of being an upper-class woman in Victorian London, even if one strips away the elements of Stoker’s misogynist perspective. The modern sensibility and almost militant feminist outlook that Lucy’s been given in this story simply don’t fit the period, even for a woman like Charlotte Perkins Gilman. While one would expect some reimagining, the hatred for men that Kiste’s Lucy continually espouses is used to bash the reader over the head repeatedly, something which becomes incredibly tedious by the end.