Philo Vance (1943-45, 1945, 1946-52) aired “The Eagle Murder Case” several times, this airing being on September 26, 1946 as the first, the debut episode of the 1946-52 run. The number of total aired episodes is unknown due to the lack of information on the 1943-45 run, though a good estimate combining the other two runs comes close to 120. This is but the second episode of this fine show we have showcased here, the only other being in June of 2018. For newcomers and for those needing to refresh their memories from that first offering, we reprise (with minor variation) the initial background information.

Philo Vance (1943-45, 1945, 1946-52) aired “The Eagle Murder Case” several times, this airing being on September 26, 1946 as the first, the debut episode of the 1946-52 run. The number of total aired episodes is unknown due to the lack of information on the 1943-45 run, though a good estimate combining the other two runs comes close to 120. This is but the second episode of this fine show we have showcased here, the only other being in June of 2018. For newcomers and for those needing to refresh their memories from that first offering, we reprise (with minor variation) the initial background information.

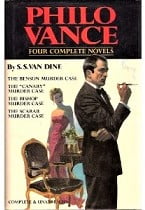

The character of detective Philo Vance was the brainchild of S. S. Van Dine (pseudonym of Willard Huntington Wright, 1887-1939). Wright would pen 12 Philo Vance novels between 1926 and 1939, the first of which was The Benson Murder Case (1926) and the last being The Winter Murder Case which he finished shortly before his death in April of 1939. Vance was very much in the mold of the “gentleman detective” or what would come to be known as the “soft-boiled” variety of detective. He has much in common with Sherlock Holmes and Nero Wolfe in that he was in possession of a giant intellect, though his arrogance and aloofness surpassed that of the former detectives and put many off. As Wright himself wrote of his character (via Van Dine) in The Benson Murder Case: “Vance was what many would call a dilettante, but the designation does him an injustice. He was a man of unusual culture and brilliance. An aristocrat by birth and instinct, he held himself severely aloof from the common world of men. In his manner there was an indefinable contempt for inferiority of all kinds. The great majority of those with whom he came in contact regarded him as a snob. Yet there was in his condescension and disdain no trace of spuriousness. His snobbishness was intellectual as well as social. He detested stupidity even more, I believe, than he did vulgarity or bad taste. I have heard him on several occasions quote Fouché’s famous line: C’est plus qu’un crime; c’est une faute. And he meant it literally.

“Vance was frankly a cynic, but he was rarely bitter; his was a flippant, Juvenalian cynicism. Perhaps he may best be described as a bored and supercilious, but highly conscious and penetrating, spectator of life. He was keenly interested in all human reactions; but it was the interest of the scientist, not the humanitarian.

“Vance’s knowledge of psychology was indeed uncanny. He was gifted with an instinctively accurate judgement of people, and his study and reading had coordinated and rationalized this gift to an amazing extent. He was well grounded in the academic principles of psychology, and all his courses at college had either centered about this subject or been subordinated to it…

“He had reconnoitered the whole field of cultural endeavor. He had courses in the history of religions, the Greek classics, biology, civics, and political economy, philosophy, anthropology, literature, theoretical, and experimental psychology, and ancient and modern languages. But it was, I think, his courses under Münsterberg and William James that interested him the most.”

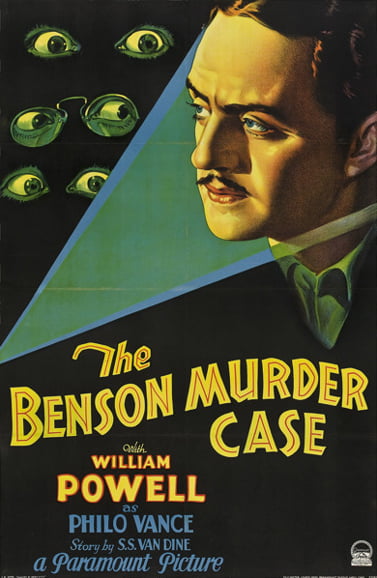

Unfortunately (or fortunately as is your preference), the radio and film portrayals of Vance toned down his aloof disdain for the common man and made him more likable for audiences. Speaking of the films, there were a dozen adapted from 1929 through 1940. There were a trio of later films made in 1947 but they had nothing to do with the novels and little relationship to the Vance character. Of the first five films (two in 1929, two in 1930–one being The Benson Murder Case, and the fifth in 1933) William Powell starred in four, while future Sherlock Holmes film star of the 1940s, Basil Rathbone, starred in the fourth (The Bishop Murder Case, 1930). The final Powell role as Vance came with 1933’s The Kennel Murder Case. Such was Powell’s popularity and connection with the movie-going audience that in 1934, barely a year later, he would co-star with Myrna Loy in the first of the classic films adapted from Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man detective novels and stories.

Unfortunately (or fortunately as is your preference), the radio and film portrayals of Vance toned down his aloof disdain for the common man and made him more likable for audiences. Speaking of the films, there were a dozen adapted from 1929 through 1940. There were a trio of later films made in 1947 but they had nothing to do with the novels and little relationship to the Vance character. Of the first five films (two in 1929, two in 1930–one being The Benson Murder Case, and the fifth in 1933) William Powell starred in four, while future Sherlock Holmes film star of the 1940s, Basil Rathbone, starred in the fourth (The Bishop Murder Case, 1930). The final Powell role as Vance came with 1933’s The Kennel Murder Case. Such was Powell’s popularity and connection with the movie-going audience that in 1934, barely a year later, he would co-star with Myrna Loy in the first of the classic films adapted from Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man detective novels and stories.

For the 1945 summer replacement series, native-born Puerto Rican actor (Tony {1947} and Oscar {1950} award winner, both for his portrayal of Cyrano de Bergerac) Jose Ferrer (1912-1992), would play Vance, and his portrayal is considered by critics and lovers of the series to be one of the best. For the much longer 1946-52 run, Jackson Beck (photo top right, 1912-2004) would play Vance, and many consider his performance to be the penultimate one, Ferrer notwithstanding. Beck is also known as the announcer for the much beloved The Adventures of Superman radio series (1940-51), and for the voice of Bluto in the series of short animated Popeye features begun in 1933 and shown in theaters across the country.

“The Eagle Murder Case” begins with an ambulance attendant removing an injured man from a car accident, placing him on a stretcher and then sliding him directly into the rear of the ambulance. The injured party, one Mr. Dalton, has broken bones but no other apparent injuries. On the way to the hospital he begs the attendant not to give him a hypo for pain, but soon dies. When examined, a knife is found embedded in his side and is the obvious cause of death. But how? He had no knife wound after being removed from the car, only broken bones. The occupants of the wrecked car are the man’s wife and two business partners, all unharmed. Aside from the ambulance attendant they are the only possible suspects in the man’s murder. Enter Philo Vance, who must find not only a motive for the man’s murder, but who could have possibly done it. This is a real puzzler and is bound to drive you crazy as you match wits with Philo Vance in his attempt to ferret out who done it and why, in the most strange affair of “The Eagle Murder Case.”

Play Time: 26:27

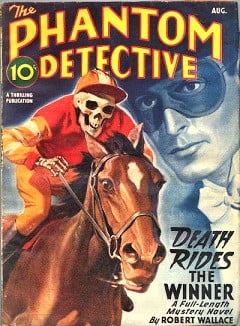

{Black Mask (1920-1951) was the premiere detective/crime magazine of its time and a regular selection for the mystery/detective lover in the neighborhood gang whenever they made one of their many journey’s to the corner newsstand. It was a bi-monthly the year before and the year after this one, but somehow managed 7 issues in 1946. Mammoth Detective (1942-1947) began with high ambitions in 1942, with a projected page count of a whopping 322 pages and a monthly schedule, but the advent of WWII dealt it a blow from which it would never recover. Due to the paper shortage during the war, the magazine quickly went from its projected 322 page count to a still respectable 178 per issue but was reduced to 9 issues in 1946 and in 1947 would close shop after only 5 years. The Phantom Detective (1933-1953) began as a monthly and remained so for many years, but when WWII hit it went to a bi-monthly publication schedule and then to a quarterly near the end of its run. It put 5 issues in the hands of its readership in 1946.]

[Left: Black Mask, Sept. 1946 – Center: Mammoth Detective, Sept. 1946 – Right: Phantom Detective, Aug. 1946]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.