“Small Discrete Intervals from a Sample Size of One” by J. Steven York

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

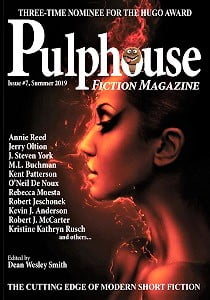

Of the dozen original stories in the latest issue of Dean Wesley Smith’s multi-genre magazine, all but two are science fiction or fantasy. The exceptions are a nostalgic tale about the first racially integrated casino in Las Vegas (“Moulin Rouge”), and a crime story featuring a terrorist with a very strange agenda (“A Choose Your Own Fangle Adventure”).

“Small Discrete Intervals from a Sample Size of One” by J. Steven York takes place after an unspecified disaster eliminated all life on Earth. An artificial intelligence, spontaneously formed from computers and other equipment left behind by humanity, uses DNA samples to recreate many organisms. Among these is a single human being. The story traces his life from birth to death, and his relationships with the AI, a robot in the form of a woman built by the AI, and a recreated dog.

The author blends intriguing science fiction concepts with an insightful portrait of the only human character. The story is a quiet but powerful study of loneliness, certain to touch the reader’s emotions.

Similar in theme and mood, “Daisy’s Heart” by Robert J. McCarter features a girl whose mother dies when the child is very young. Her father becomes emotionally distant, so the girl’s closest relationship is with a robot servant. The child grows up to be an expert in robotics. She faces the loss of her robot friend to obsolescence, and the challenge of reconciliation with her estranged father.

The story’s futuristic content is completely believable, as is the emotional odyssey of the protagonist. The author avoids sentimentality through a calm narrative style, which gives the characters’ feelings great sincerity.

In “Introducing Alligators” by Preston Dennett, people can have their brains temporarily or permanently transplanted into the bodies of animals. The main character decides to spend the rest of her life as an alligator. The ending provides a minor twist, which may chill the reader’s spine, but there is not much else to this story beyond its basic premise.

The villain in “The Mouse is Watching” by S. Andrew Swann is an all-powerful media mogul, thought to be long dead, but secretly kept alive through advanced technology. Although unnamed, this megalomaniac is clearly supposed to be a famous person from real life. (The title of the story is a strong clue.) The narrator receives a manuscript revealing all the dark secrets of the antagonist, leading to a dangerous encounter.

This darkly comic satire on the sinister power of gigantic corporations packs a powerful punch. Its depiction of a deceased celebrity of yesteryear as a figure of pure evil is in questionable taste.

“Dreams of Memories Never Lived” by Rob Vagle is a fantasy of life after death. A man dies of a heart attack at the age of sixty-four. As a peculiar kind of ghost, he witnesses his own funeral, but his corpse is that of a much younger man. He also meets the ghost of his daughter, even though he never sired children. Together they explore the mystery of these contradictory former lives.

The premise is imaginative and the characters are appealing. There seems to be no logic to the strange afterlife of multiple timelines, weakening the story’s effect on the reader.

The narrator of “A Pathetic Excuse for a Dragon” by David H. Hendrickson is an outcast, because she cannot fly or breathe fire. She yearns for the affection of a handsome, healthy dragon, but believes that her love is doomed to be unrequited. There are no surprises in this simple little fable. Although predictable, the outcome of this star-crossed romance may raise a smile.

“Maddie Sue’s Locket” by C.A. Rowland is a fantasy of backwoods magic. The narrator inherits a locket from her mother. It binds her to her husband throughout life, and beyond. Despite this supernatural connection, their marriage faces a crisis when the husband suspects, for a valid reason, that he is not the father of their daughter. Complicating matters is the fact that the girl is romantically involved with a boy who may be her half-brother. The truth comes out only after both husband and wife are dead, although this is not the end of their relationship as lovers.

The rural background is convincing, and the characters come across as real people living in a real place. The narrator’s actions, only revealed in full at the end of the story, are likely to seem improper to some readers. The subplot of possible incest is dealt with in a manner that too quickly dismisses the problem.

In “Good Fences Make Good Neighbors” by Teri J. Babcock, the government uses matter-transforming technology to change houses into sugary treats. This science fiction version of the familiar tale of Hansel and Gretel ends with a touch of black comedy. It will amuse some readers, but others will find it silly and illogical.

“Lost Book” by Ryan M. Williams takes place in a vast library that combines magic with technology. A living, enchanted book appears from nowhere. The protagonist tries to figure out where it belongs, but the book has its own motive, endangering the entire library. This light fantasy has special appeal for bibliophiles, although much of the fantastic content is arbitrary, and the protagonist solves the crisis all too quickly.

The main character in “Acceptable Losses” by Dayle A. Dermatis is a biologist who develops a way to grow large amounts of edible seaweed in a barren area of Africa, providing food for those who are starving. Her process is successful, but she pays a terrible price when it proves to be deadly to a small percentage of those who make use of it. The story concludes in an open-ended fashion, as the biologist faces the difficult question of whether the benefit of her procedure is worth the risk.

Fully developed characters make the tragedy at the heart of this story seem very real. The moral crisis facing the protagonist is an important one. By leaving the answer up to the reader, the author forces us to contemplate vital ethical issues concerning the welfare of the many and the sacrifice of the few.

Victoria Silverwolf had to think about whether a couple of these stories were really science fiction or fantasy, which tells you something about the nature of the magazine.

Pulphouse #7, Summer 2019

Pulphouse #7, Summer 2019