“The Fur Tsunami” by Kent Patterson

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

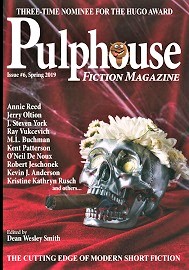

Editor Dean Wesley Smith offers eleven original works of fiction in the latest issue of this quarterly publication.

“The Fur Tsunami” by Kent Patterson appears here for the first time, although the author passed away in 1995. It begins simply enough, with the protagonist looking for her missing cats. It soon turns out that all the cats in the world are trying to get to Egypt, their ancestral home. The woman follows them, leading to a final confrontation at the Sphinx.

The main appeal of this story is the main character’s progression from a lonely, timid figure, emotionally shattered when her husband leaves her for another woman, into a bold, heroic adventurer. The whimsical premise may seem silly to some, but is likely to please ailurophiles.

In “Unnatural Law” by J. Steven York, supernatural beings exist in the modern world, but a spell keeps most ordinary people ignorant of them. The narrator is a human attorney who works on cases relating to magical creatures. He speaks to a man who, against his will, is now aware that such things exist. He tries to convince him to testify in a trial involving a violent attack on a woman of the Fey by a human male.

The concept is an interesting one, and the author makes it very believable. Vampires and fairies are as real as the human characters. The story ends quickly, with a hint about the narrator’s past, which is likely to frustrate readers looking for a more complete resolution.

Set on the Moon in a high-tech future, “A Cherub by Any Other Name” by Annie Reed features a man who creates wondrous inventions, such as instantaneous matter transmission. His latest project is a time machine, which seems to be a failure. Out of nowhere, a tiny fellow dressed like Cupid appears in the device. He turns out to be from another dimension, and is looking for his wife. Their conversation changes the inventor’s life.

This madcap farce, with its diapered little man, puffing on smelly cigars, provides some amusement. Flashback scenes, relating the inventor’s attempt to enhance color vision, are irrelevant to the main plot.

In “PMS and a Hand Grenade” by Brenda Carre, a woman working at a daycare center meets an attractive man and his young son. After a realistic opening sequence, the story becomes pure fantasy. The man turns out to be the Devil, and his son has the power to make metaphoric statements, such as “button your lip,” horribly literal. The woman finds a way to curse the Devil in return.

The sassy and resourceful heroine is appealing, and fans of dark comedy will appreciate the plot’s twists and turns. Those who are easily offended may find it a little vulgar.

The main character in “The Disappearing Neighborhood” by Robert J. McCarter is an elderly widower. As he walks his dog through the area where he has lived for many years, empty lots appear where there should be houses. Neighbors vanish, without any sign that they ever existed. The story ends with a bittersweet resolution.

A sensitive, beautifully written allegory of the inevitable losses of aging, the plot progresses in a fashion that is as logical and inevitable as it is heartbreaking. The powerful emotional appeal of this story ensures that it will long endure in the memories of all who read it.

“Knock on Wood” by Rob Vagle also involves a man who lost his wife to death years ago. He never leaves his house, opening the front door only to receive grocery deliveries. One day a little girl knocks on his door. He peers through the peephole to see changes in the world outside. The girl returns repeatedly, and each time reality alters. A final transformation brings the man out of his home at last.

This is a mysterious tale, haunting in its implications, but not always clear in its intention. The strange little girl is both malevolent and benign, showing the man things that are either frightening or appealing. The ending appears to be optimistic, but some might interpret it in a darker way.

In “Double Date” by William Oday, a pair of conjoined twins—two sisters sharing the same body from the shoulders down—work as hired killers. Despite their shared profession, they have very different personalities. One is more intellectual, the other more sensual. Their latest target is a man they both find attractive. They strike up a conversation with the fellow as a way of preparing for the kill, only to discover that he has a secret of his own.

The bizarre nature of the assassins holds the reader’s attention, even if they never seem plausible. One could hardly imagine killers that are more conspicuous. The way in which the intended victim shows no astonishment when he meets them is difficult to believe. The ending also strains credibility.

The narrator of “Sleeping With the Devil” by Kelly Washington is from the twenty-third century. Her profession is retrieving lost objects for a queen. Her current assignment is to obtain a worthless brooch stolen by Lucifer. She travels to Hell, and makes a bargain with the handsome, charming demon lord. He will return the brooch, if she will dance with him. Of course, there is more to it than that.

The time travel aspect of the plot is jarring, as there is nothing else futuristic in the story. Hell resembles Regency England, and what little we learn about the year 2221 makes it seem equally anachronistic.

“Upgrade? Up Yours” by Jerry Oltion is a satiric tale set in a time when people have computerized body enhancements, from prosthetic limbs to shapeshifting tattoos. Whether the wearers like it or not, the devices undergo frequent upgrades. These often cause unwanted changes. When things finally get completely out of hand, a protest movement begins.

Anyone who has ever had to wait while a computer underwent an unnecessary upgrade will sympathize with the characters’ problems. In addition to the story’s theme, it contains a touch of slightly bawdy comedy, which readers may or may not enjoy.

The narrator of “Between” by M. L. Buchman lives in a future world where the sudden loss of ice caps in Greenland and Antarctica led to the flooding of much of the planet. She also has a more personal problem. Her emotions do not fit her experiences. Eventually she discovers that her mind communicates with that of a parallel version of herself in an alternate world, which underwent its own disaster. The two selves work to find a better existence for them both.

The idea is intriguing, and the two different worlds are both interesting examples of apocalyptic settings. Unfortunately, the story stops in an open-ended fashion, without a real conclusion.

In “The Thousandth Atlas” by Robert Jeschonek, seemingly meaningless actions practiced by certain people save the world from destruction. The narrator, after a tragic loss, seeks to protect these people, and ensure that they keep performing the activities that protect reality. His plan to make sure a woman does not rid herself of her obsessive-compulsive behavior leads to a dangerous situation.

The premise is a unique one, and the author manages to convey the narrator’s desperate struggle to stave off universal disaster. The method he uses to preserve the woman’s repetitive actions seems foolhardy, and the way in which the ensuing crisis resolves makes use of a deus ex machina.

Victoria Silverwolf was pleasantly surprised to discover that all the new stories in this issue were science fiction or fantasy.

Pulphouse #6, Spring 2019

Pulphouse #6, Spring 2019