Boston Blackie (1944, 1945-1950) aired “TV Poisoning” on December 20, 1945 as the 49th episode of the 220 from its 1945-50 run. This is but the second of this program we have aired here, so for newcomers I recap the rather fascinating history of the man behind the stories that eventually led to Boston Blackie coming to radio, film, and even early television. The show was produced originally in 1944 as a 13-episode summer replacement for the Amos & Andy Show. It proved popular enough and aired its first show in April of 1945, but under different ownership (ZIV productions, running on NBC in its own time slot), format, and actors. Chester Morris played Boston Blackie while Richard Lane played the part of Inspector Farraday in the 1944 replacement episodes, though in its official 1945 incarnation Richard Kollmar (1910-1971, photo middle right) became Boston Blackie, primarily due to contractual film obligations that stood in the way of Chester Morris continuing the role.

Boston Blackie (1944, 1945-1950) aired “TV Poisoning” on December 20, 1945 as the 49th episode of the 220 from its 1945-50 run. This is but the second of this program we have aired here, so for newcomers I recap the rather fascinating history of the man behind the stories that eventually led to Boston Blackie coming to radio, film, and even early television. The show was produced originally in 1944 as a 13-episode summer replacement for the Amos & Andy Show. It proved popular enough and aired its first show in April of 1945, but under different ownership (ZIV productions, running on NBC in its own time slot), format, and actors. Chester Morris played Boston Blackie while Richard Lane played the part of Inspector Farraday in the 1944 replacement episodes, though in its official 1945 incarnation Richard Kollmar (1910-1971, photo middle right) became Boston Blackie, primarily due to contractual film obligations that stood in the way of Chester Morris continuing the role.

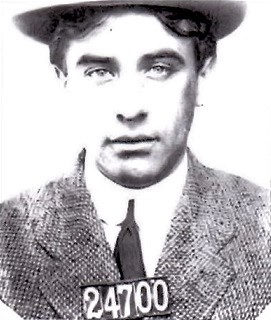

The Boston Blackie character first appeared in a series of short stories, the first in 1914 in The American Magazine by author Jack Boyle (1881-1928, photo top right). Boyle led a short but colorful life, spending two stints in prison for passing bad checks and forgery. Details of his life between the years 1908 and 1914, according to this website, are scarce, though through diligent research and some luck it was discovered that Boyle spent 10 months in San Quentin (mug shot top right) beginning on December 17, 1910 and was released the following October; though a few years later in 1914 he would be serving another stint in the joint, this time in a Colorado state prison for much the same offenses.

.jpg)

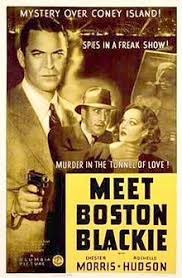

Turning what he knew into what he would write, Boyle then created the fictional character of Boston Blackie, a reformed jewel thief and safe-cracker who had done prison time and was now an “Enemy to those who make him an enemy. Friend to those who have no friend.” Blackie is aided in his capers by his rather slow-witted sidekick Runt, and is hounded by police Inspector Faraday (the police inspector working against, or trying to pin the blame for crimes against the hero a popular formula that became a staple, i.e. The Shadow, Rocky Jordan, The Green Hornet, and many others in print, radio, and film). Boyle’s stories hit the right chord and a whopping 11 silent films featuring Blackie were made from 1918-1927. The series was picked up in 1941 with Chester Morris in the lead as Blackie in Meet Boston Blackie, the first of what would be 14 total films, the final one to hit the silver screen in 1949 and all starring Chester Morris. When the new medium of television became all the rage Boston Blackie was among the first to jump on board with Boston Blackie. It debuted in 1951, ran for 58 half-hour episodes until 1953, and would then air in syndication for almost another ten years. An interesting side note is that of Blackie’s 58 TV shows 32 were shot in color, while the remaining 26 were shot in black & white, shooting in color something unheard of at the time (and expensive) for an early television show. But the producers were ahead of their time and gambled that when color became more widely available there would be a market for color reruns. Thus, Boston Blackie would join the ranks of the few early TV shows also shot at least in part in color, Superman and The Cisco Kid two favorites coming to mind.

Turning what he knew into what he would write, Boyle then created the fictional character of Boston Blackie, a reformed jewel thief and safe-cracker who had done prison time and was now an “Enemy to those who make him an enemy. Friend to those who have no friend.” Blackie is aided in his capers by his rather slow-witted sidekick Runt, and is hounded by police Inspector Faraday (the police inspector working against, or trying to pin the blame for crimes against the hero a popular formula that became a staple, i.e. The Shadow, Rocky Jordan, The Green Hornet, and many others in print, radio, and film). Boyle’s stories hit the right chord and a whopping 11 silent films featuring Blackie were made from 1918-1927. The series was picked up in 1941 with Chester Morris in the lead as Blackie in Meet Boston Blackie, the first of what would be 14 total films, the final one to hit the silver screen in 1949 and all starring Chester Morris. When the new medium of television became all the rage Boston Blackie was among the first to jump on board with Boston Blackie. It debuted in 1951, ran for 58 half-hour episodes until 1953, and would then air in syndication for almost another ten years. An interesting side note is that of Blackie’s 58 TV shows 32 were shot in color, while the remaining 26 were shot in black & white, shooting in color something unheard of at the time (and expensive) for an early television show. But the producers were ahead of their time and gambled that when color became more widely available there would be a market for color reruns. Thus, Boston Blackie would join the ranks of the few early TV shows also shot at least in part in color, Superman and The Cisco Kid two favorites coming to mind.

“TV Poisoning” finds Blackie and his lovely Mary at the home of a friend who has let them watch his new television set while he is away. They are keen to watch a live show wherein a local city official is about to indict a criminal live, right there on the air. Just before the announcement is made, however, the official keels over dead, murdered by poison. The who and how are the focus of the investigation, for there were three other officials in the tv studio and on camera when the fourth died, and all four had eaten the same meal and had drunk the same water–yet only this man had died of poison. An interesting conundrum for Blackie to solve, and it gets more complicated than you might think, giving Blackie all he wants in this dandy episode.

I was also intrigued with the fact that the story revolved around the relatively new invention of television, so did some informational digging. When this story took place in 1945 the population of the United States was 140 million. There were estimated to be only 10,000 commercial tv sets in the country, and only 0.5% of households a year later in 1946 had a set. Four years later in 1950 there were 6 million tv sets. And today in the United States it is estimated that just over 300 million tv sets exist–one for almost every man, woman, and child in the country. The sharp rise in sets sold after the war ended in 1945 was due to the fact that the government had put a virtual halt to their manufacture during the war (raw materials were needed for the war effort), and this restriction was lifted in late 1945. So sales of the relatively new invention skyrocketed and television was all the rage among those who could afford them. And this explains at least in part the enthusiasm displayed by Blackie and Mary when invited to their well off friend’s home to watch the live tv program featured in this episode.

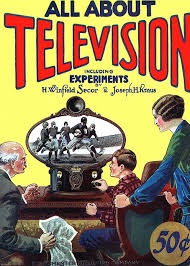

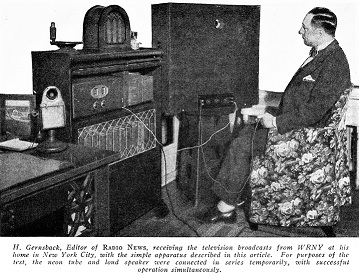

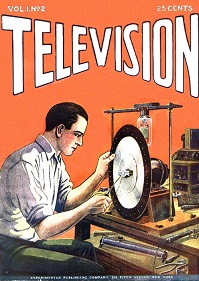

As an aside and for science fiction fans, there is a tie-in with early television and Hugo Gernsback, the publisher of the first SF magazine (Amazing Stories, April 1926) and whose first name was given to the field’s Achievement Award, the Hugo. Not only did Gernsback own and operate radio station WRNY out of New York City from 1925-29 (it was sold in 1929 to Curtiss Aeroplane when Gernsback went bankrupt, and eventually went defunct in 1934), he is reputed to have published the very first magazine devoted to television. Unfortunately, the magazine lasted but two issues and folded along with the rest of Gernsback’s magazines in 1929 due to the bankruptcy.

(Left: All About Television, Vol. 1 #1, 1927 – Center: Gernsback watches TV in his home {not much to watch} broadcast from his radio station WRNY in August of 1928 – Right: Television, Vol. 1 #2, July 1928)

Play Time: 26:17

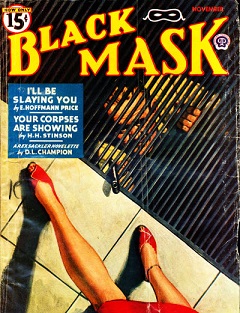

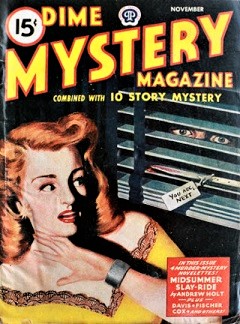

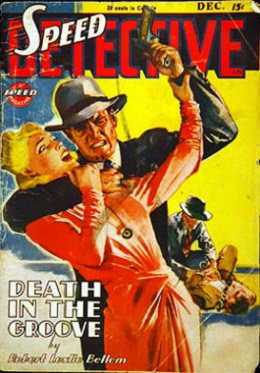

{Pumped up for more noir detective fare after listening to this Boston Blackie episode, the would-be sleuths of the neighborhood headed for the corner newsstand for one final look-see for new magazines before Christmas. Black Mask (1920-51) was always a clear-cut must have when they were in the mood for no holds barred intrigue and violence of all sorts. Sharp-eyed dark fantasy/weird fiction readers will notice the name of E. Hoffman Price on the cover of this issue. BM was a bi-monthly in 1945. Dime Mystery (1932-50) was a good complement to BM and there was even more straightforward down-and-dirty tales of corruption and amoral hoodlums to be brought to justice within its pages. It too was a bi-monthly in 1945. Speed Detective (1934-47) tried to hold its own in 1945 but was on its last legs. Until late 1943 it was titled Spicy Detective Stories and its crime stories (and covers) were laced with sex to attract readers. It was also a monthly until late 1943, but when it changed its name to Speed Detective to bow to the pressures of social reform in the industry, it immediately went to a bi-monthly schedule. Whether this cutback was due to the paper shortage during the war or for lack of interest in its now more inoffensive format remains to be seen. An argument could be made for a little bit of both combining to foreshadow the magazine’s demise in 1947.}

[Left: Black Mask, Nov. 1945 – Center: Dime Mystery, Nov. 1945 – Right: Speed Detective, Dec. 1945]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.