Boston Blackie (1944, 1945-1950) aired “A New Face for Joe Harvey” on November 5, 1946 as the 82nd episode of the 220 from its 1945-50 run. It was produced originally in 1944 as a 13-episode summer replacement for the Amos & Andy Show. It proved popular enough and aired its first show in April of 1945, but under different ownership (ZIV productions, running on NBC in its own time slot), format, and actors. Chester Morris played Boston Blackie while Richard Lane played the part of Inspector Farraday in the 1944 replacement episodes, though in its official 1945 incarnation Richard Kollmar (1910-1971, photo middle right) became Boston Blackie, primarily due to contractual film obligations that stood in the way of Chester Morris continuing the role.

Boston Blackie (1944, 1945-1950) aired “A New Face for Joe Harvey” on November 5, 1946 as the 82nd episode of the 220 from its 1945-50 run. It was produced originally in 1944 as a 13-episode summer replacement for the Amos & Andy Show. It proved popular enough and aired its first show in April of 1945, but under different ownership (ZIV productions, running on NBC in its own time slot), format, and actors. Chester Morris played Boston Blackie while Richard Lane played the part of Inspector Farraday in the 1944 replacement episodes, though in its official 1945 incarnation Richard Kollmar (1910-1971, photo middle right) became Boston Blackie, primarily due to contractual film obligations that stood in the way of Chester Morris continuing the role.

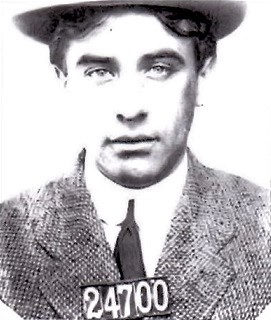

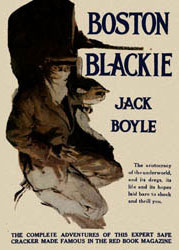

The Boston Blackie character first appeared in a series of short stories, the first in 1914 in The American Magazine by author Jack Boyle (1881-1928, photo top right). Boyle led a short but colorful life, spending two stints in prison for passing bad checks and forgery. Details of his life between the years 1908 and 1914, according to this website, are scarce, though through diligent research and some luck it was discovered that Boyle spent 10 months in San Quentin (mug shot top right) beginning on December 17, 1910 and was released the following October; though a few years later in 1914 he would be serving another stint in the joint, this time in a Colorado state prison for much the same offenses.

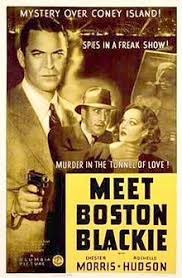

Turning what he knew into what he would write, Boyle then created the fictional character of Boston Blackie, a reformed jewel thief and safe-cracker who had done prison time and was now an “Enemy to those who make him an enemy. Friend to those who have no friend.” Blackie is aided in his capers by his rather slow-witted sidekick Runt, and is hounded by police Inspector Farraday (the police inspector working against, or trying to pin the blame for crimes against the hero a popular formula that became a staple, i.e. The Shadow, Rocky Jordan, The Green Hornet, and many others in print, radio, and film). Boyle’s stories hit the right chord and a whopping 11 silent films featuring Blackie were made from 1918-1927. The series was picked up in 1941 with Chester Morris in the lead as Blackie in Meet Boston Blackie, the first of what would be 14 total films, the final one to hit the silver screen in 1949 and all starring Chester Morris. When the new medium of television became all the rage Boston Blackie was among the first to jump on board with Boston Blackie. It debuted in 1951, ran for 58 half-hour episodes until 1953, and would then air in syndication for almost another ten years. An interesting side note is that of Blackie’s 58 TV shows 32 were shot in color, while the remaining 26 were shot in black & white, shooting in color something unheard of at the time (and expensive) for an early television show. But the producers were ahead of their time and gambled that when color became more widely available there would be a market for color reruns. Thus, Boston Blackie would join the ranks of the few early TV shows also shot at least in part in color, Superman and The Cisco Kid two favorites coming to mind.

Turning what he knew into what he would write, Boyle then created the fictional character of Boston Blackie, a reformed jewel thief and safe-cracker who had done prison time and was now an “Enemy to those who make him an enemy. Friend to those who have no friend.” Blackie is aided in his capers by his rather slow-witted sidekick Runt, and is hounded by police Inspector Farraday (the police inspector working against, or trying to pin the blame for crimes against the hero a popular formula that became a staple, i.e. The Shadow, Rocky Jordan, The Green Hornet, and many others in print, radio, and film). Boyle’s stories hit the right chord and a whopping 11 silent films featuring Blackie were made from 1918-1927. The series was picked up in 1941 with Chester Morris in the lead as Blackie in Meet Boston Blackie, the first of what would be 14 total films, the final one to hit the silver screen in 1949 and all starring Chester Morris. When the new medium of television became all the rage Boston Blackie was among the first to jump on board with Boston Blackie. It debuted in 1951, ran for 58 half-hour episodes until 1953, and would then air in syndication for almost another ten years. An interesting side note is that of Blackie’s 58 TV shows 32 were shot in color, while the remaining 26 were shot in black & white, shooting in color something unheard of at the time (and expensive) for an early television show. But the producers were ahead of their time and gambled that when color became more widely available there would be a market for color reruns. Thus, Boston Blackie would join the ranks of the few early TV shows also shot at least in part in color, Superman and The Cisco Kid two favorites coming to mind.

“A New Face for Joe Harvey” is somewhat traditional in that it deals with a crook getting a face job from a plastic surgeon in order to hide his true identity (which may be for monetary gain, to hide from those he has double-crossed, or for some other unknown reason). If only from a superficial viewpoint, this altering of one’s identity via plastic surgery gambit brings to mind the classic Humhrey Bogart/Lauren Bacall 1947 film Dark Passage, where Bogart as innocent victim Vincent Parry alters his face to elude the authorities until he can clear his name. So what is the reason for Joe Harvey’s new face in this episode of Boston Blackie (curiously airing just under a year before Dark Passage hit theaters, which was itself based on the 1946 novel of the same name by David Goodis; was this 1946 radio script inspired in its own way by the book’s then current popularity?), and what has it got to do with Blackie to get him involved? There’s only one way to find out, and that is to give this episode a listen.

Play Time: 25:15

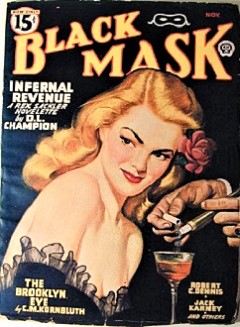

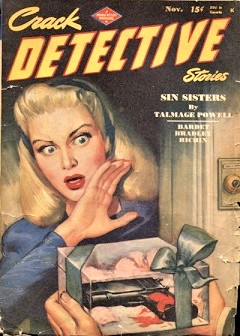

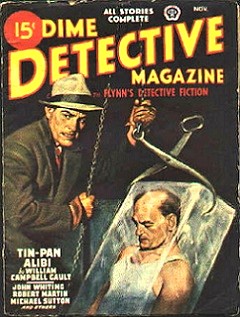

{Listening to Boston Blackie got the neighborhood gang in the mood for more hardcore, noir crime action, so a visit to the corner nesstand was definitely in order. Black Mask (1920-51) was the premiere example of its type, featuring most of the top crime and mystery authors of the time, and was home to many of what are now considered classic stories of the genre. Notice here the name C. M. Kornbluth (1923-58) in the lower left-hand corner of the cover, one of SF’s fondly remembered names. Born in 1923, Kornbluth was but 23 when this story was published. He would live but 15 years more, alas, dying in March of 1958 at age 34 from a heart attack after shoveling snow. Though it published 7 issues in 1946, Black Mask ended the year as a bi-monthly. Crack Detective (1938-57) enjoyed a lengthy and profitable run just short of 20 years, though its major achievement might be that it lasted as long as it did after suffering no fewer than 8 name changes to confuse its readers. It was a bi-monthly in 1946. Dime Detective (1931-53) was also a long-running favorite and reliable purchase for lovers of the down and dirty, no holds barred type of crime fiction. It was a monthly in 1946.}

[Left: Black Mask, Nov. 1946 – Center: Crack Detective, Nov. 1946 – Right: Dime Detective, Nov. 1946]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.