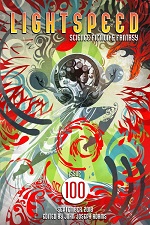

Lightspeed #100, September 2018

Lightspeed #100, September 2018

“Her Monster, Whom She Loved” by Vylar Kaftan

Reviewed by Gyanavani

This month Lightspeed celebrates its 100th issue with a bumper crop of interesting science fiction and fantasy material.

Vylar Kaftan’s “Her Monster, Whom She Loved” is a power-packed creation myth.

Ammuya, the mother of five hundred murdered gods, is the only existing divine power that can save the universe (and in the process herself) from the all-consuming rage of the lone monster she has also birthed. But in neither direct struggle nor strategically planned warfare, does she manage to overthrow her rebellious son. Its only when she understands that she and her son are one and alike monstrous because of their infinite power does she come up with a plan that will succeed in keeping their unlimited superiority in check.

Most creation tales (think Tolkien) use traditional mythic techniques to create beautiful structures that explain our universe and its formation in a poetically true fashion. Vylar Kaftan has added an interesting twist to the structure. She successfully uses our scientific understanding of space and the universe to create a deeply satisfying myth about the Big Bang and how the universe came into being.

We meet the protagonists of the Carrie Vaughn story, “Harry and Marlowe and the Secret of Ahomana” as their air ship crash lands on a deserted island. In the alternative universe in which Harry and Marlowe reside, an alien civilization more technologically advanced than we humans on this Earth, have visited us and left gifts behind for us. Harry, who is a princess of Wales and next in line to the throne has set out with a trusted friend, Marlowe, to collect as many of these artifacts that they can find. Europe, as usual is in turmoil, Germany and England are at loggerheads and have been fighting for a while and these artifacts, used to create sophisticated weaponry, could well be the tipping point.

On the island Harry and her injured friend Marlowe are rescued by members of what look like a primitive tribe, but are surprisingly technologically more advanced than Harry’s own people. Thus Harry learns that fortuitously they have connected with a tribe that had been trained by an alien being (now dead) who they revered as their teacher and spiritual leader. But whatever hopes she has of convincing these people to join their force in her country’s favor is dashed to pieces when she learns that she and Marlowe cannot leave the island till the end of their days. That is the only way the people of Ahomana can keep their existence a secret.

The utopian society of Ahomana is tempting but Harry’s duty to her people and her throne will not let her remain idle. She concocts an elaborate escape plan but is foiled not only by the people of Ahomana’s vigilance but also by her own unwillingness to indulge in robbery and bloody murder.

Carrie Vaughn’s ambitious tale centers around her strong world building skills. The utopian culture as well as the mainstream universe which follows a different historical path from ours, tread well-defined but parallel tracks. So we expect the climax to be a major confrontation between these two societies. But Vaughn presents a more peaceful answer which I like and yet I feel strangely cheated of the big bold blow-up that all along I had anticipated with a heavy heart.

“The Last to Matter,” Adam-Troy Castro’s gem of a novelette, tells the story of a man, Kayn, who rejects the degenerate methods that humans of his time use to obliterate the memory of Earth’s disintegration into a desert and instead embraces death as the most dignified choice. Kayn lives at least a millennium in the future. His world is ruled by slowly decaying machines that control physical comforts such as hunger and disease and emotional responses such as love and fear.

At the outset this novelette reads like a cynical expose of the human condition but along the way it evolves into a heart stopping, beautiful rendering of “The Pilgrim’s Progress.” The episodic structure of the story makes it difficult to give greater detail. But the crucial reason for my silence is because any summary that I might provide would not do justice to the amazing grace of Adam-Troy Castro’s writing. Reader, read this story!

In “Abandonware” Genevieve Valentine tells the sad, but not hopeless, non-linear story of Christine who suffers from abandonment issues (parents divorced, mother already dead of cancer, father remarried with a new family) making it hard for her to connect with people. Through the course of the story, we learn that she had to sell her mother’s house to pay healthcare bills, that she loses her job because of her fixation with an online game, and that she is evicted from her apartment for being unable to pay her rent.

What makes the story interesting is the manner in which Valentine threads an invisible deer through an online game whose setting conveys romance and hope. She also uses a detective as an image of omniscience and the detective form as a means of locating the disintegrating personality of our heroine, Christine.

In the short story “Jump” by Cadwell Turnbull a young couple in the heady throes of love casually teleport themselves from the park where they were walking to their home a few miles away. The couple marries but this magical event that should have bound them tightly actually ends up destroying their relationship.

The woman, as usual the more mature partner, simply accepts the magical memory as one of the many she hopes to make with her partner. But the man cannot move on, he has to take that one memory apart and attempt a repeat of it. Sadly, every combination he asks they try ends in failure.

After four years of living in the shadow of this one memory, the woman decides to move on. When they meet for the last time, (the man who had by then understood that the woman in the present was more important to him than the miraculous past,) the two decide to teleport one last time. This time, since they both are attuned only to each other, they succeed.

“Jump” is a simple story. By printing it this magazine signals its belief that the fantasy genre has entered a new era where, like mainstream fiction, it will deal with everyday issues in this case, what keeps a marriage going, what decisions can split a loving couple, and what will join them again. However, the question does arise whether this new spectrum leaches away the excitement and reduces the form.

In “You Pretend Like You Never Met Me and I’ll Pretend Like I Never Met You” by Maria Dahvana Headley, Wells’, our forty-five-year-old hero’s, dad, who was a real magician as opposed to Wells who was only a performer of cheap tricks, makes a deal with the devil. The devil looses patience, breaks his word, and sends in his minions to collect his dues but is unexpectedly thwarted. Wells, a child then, decides to deny the entire episode and spends the next thirty years running away.

In the present, Wells is a low-paid entertainer at a birthday party where the children dare him to bring back their newly dead pal into the land of the living. Wells achieves a complicated swap, giving the devil his father’s soul and so finally burying his father and bringing the five-year-old back to his parents.

Headley has written an ambitious story but its choppy form reduces clarity. Most importantly I did not understand why the death of this child, someone unknown to Wells whose parents too are strangers to him, should impact him to the extant that he decides to have a dangerous duel with the devil. Nowhere in the character that Headley has built for Wells does she show him as indulging in gestures marked by grand generosity.