"Señora Suerte" by Tananarive Due

"The Return of the O’Farrissey" by John Morressy

"The Song of Kido" by Matthew Corradi

"Poor Guy" by Michael Kandel

"Perfect Stranger" by Amy Sterling Casil

"If You’ve Ever Been a Lady" by Michael Libling

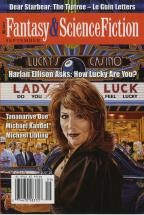

Oh, and the premise? A loser falls in love with Lady Luck.

A grim and subdued tale, "Señora Suerte" is also a treatise on the value of dignity and quality of life in the treatment of the elderly and the dying. The theme explored is not a novel one: should we persevere, and more, should we insist that others persevere, when the weight of existence itself has become a burden? There is nothing new to be found in this tale or its message, no fresh arguments or new angles, but there is poignancy in spades. Due crafts a soulful tale of quiet despair, well-written and evocative.

Next in this exercise of fortune is "Poor Guy" by Michael Kandel. Structured in a traditional tale-within-a-tale, readers are treated to a postmodern religious parable, "The Story of Brother Anselm," as told by an abbot of the Brethren of Gumby to a faith-impaired monk. Anselm, a.k.a. George, is the lowest of lowly losers; his life is a series of retributive lumps as he repays the bad karma, I mean negative tü [pronounced as the end of a sneeze or the middle of a saliva discharge? This reader can only speculate], that burdens his soul from the unfortunate build-up of transgressions from previous lives. That is, until Lady Tü herself intervenes.

This tale is as light and tongue-in-cheek as "Señora Suerte" is bleak and somber, providing a remarkable contrast of approaches to Ellison’s endeavor. Its brevity is an asset as there is an abundance of style and a minimalist measure of weighty substance here, in keeping with postmodern literature—complete with ironic silliness and self-referential mentions of pop culture, politics, and technology—which would have bogged down a lengthier work. "Poor Guy" can actually be viewed as a framework within a framework on dual levels. In addition to the abbot’s narrative, there is the original story premise, as laid out by Ellison’s challenge, upon which the tale’s narrative is draped, a scaffolding which both sparks inspiration while delineating its boundaries. Or maybe this reviewer is over-thinking a light and rolicksome ditty of a story. Yep. All hail Gumby.

Last in this trio of Ellison-spawned incarnation of luck fabrications is "If You’ve Ever Been a Lady" by Michael Libling. Denny Flett is an unsuccessful mattress salesman at a business conference in Las Vegas. True to the dictates of the endeavor, he’s an A-1 loser: cheating girlfriend, the laughingstock of his colleagues, and to top it off, newly unemployed. Then he spies her, the redhead in the elevator, the most beautiful woman he’s ever seen. And his luck changes. After a fashion.

This was the most reminiscent in tonal styling to Mr. Ellison’s distinctive voice with its richly intimate characterization and wry humor, packaged in an earthy, straightforward delivery that yet manages to provide some surprisingly brilliant turns of phrase. Utilizing the present tense to excellent effect, there’s an immediacy which immerses the reader from the first paragraph. Denny is a sleaze, unattractive and unclever, and chock full of unsympathetic personality traits. Yet, Libling succeeds in making him not only sympathetic, but also charming, despite or perhaps because of his clumsy, clueless, and misguided bumblings. You gotta love an underdog. This was my favorite of the threesome—engaging and funny, with an ultimately satisfying finale. Highly recommended.

This sprightly tale is full of fast-paced banter couched in a thick, Irish brogue. At its core, Kate is torn between duty to her father and her own wants. A reader would have to possess a heart of Adamantium not to root for Kate; I clamored for her to realize that she did not have to belong to her deadbeat da or even her curmudgeonly (but lovable) teacher, but only to herself. Regrettably, Kate’s transformation into a be-true-to-you woman of the modern age never transpired, due to a convenient, um, Mcguffin. However, she does declare what her heartfelt wishes are, which is close.

This reader would have welcomed more installments of the adventures of Kate O’ Farrissey. It would have been a treat to watch Kate grow into her power and into herself. Alas, when the world experiences the tragic loss of a gifted storyteller, it is a manifest reality that all his untold stories are lost as well. I must be contented in my certainty that Kate’s tale would surely have ended: "And they all lived happily ever after."

In "The Song of Kido" by Matthew Corradi, Jax Ridimon is searching for answers on the world of Kido, as well as a cure to the curse which haunts him. He hears the laments of the dead—their regrets, their sorrow, their pain. Ridimon yearns to understand the big question, the nature of the great beyond: what death brings and how to escape the anguish of it. He hires a guide, Phidrik, a drunken native, to help him hunt a kigrin, dragonesque and deadly aliens rumored to have ancient knowledge and wisdom beyond this universe. He hopes that by capturing a kigrin, he may interrogate it and so learn The Truth, if there is one.

Set in an alien world of swamps, where tortured souls wail beneath stagnant water, trapped in the boggy morass, the feel of this story is otherworldly and forbidding. Ridimon is a man whose obsession and fear of death has shaped his whole existence so he is trapped in a hellish limbo—unable to truly live, yet too terrified to face his fear of the unknown. This was the most innovative story in the issue. By taking traditional ghost story themes and imbuing them with a science fiction treatment, Corradi succeeds in producing a tale redolent with dread and uncertainty. The blending of science fiction elements with ghost story ones is well effected, although the discussion of FTL hyper-c Gate travel seemed unnecessary to this reader, a smattering of superfluous SFnal details unwarranted by theme or story. Still, they didn’t detract from the overall mood or message either. Recommended.

In Amy Sterling Casil‘s "Perfect Stranger," an ultrasound identified a fatal congenital heart defect before Denny was born. To save his life, his parents had him undergo an in utero gene therapy treatment. The procedure was successful, and now, at fifteen, Denny is a wunderkind: soccer star, math whiz, class president, artistic genius, and gorgeous to boot. But his beauty, brains, and brawn are due to a series of genetic enhancements. These treatments were originally initiated by his parents in a progression of well-meaning rationalizations—life-saving and life-improving. But now they’ve become de rigeur, employed at the shallowest of whimsies. And he’s not the only one. Denny’s society is becoming peppered with modified children, brilliant and beautiful, who bear only disdain for those not privy to the benefits of genetic modification.

"Perfect Stranger" is a cautionary tale on the dangers of abusing genetic tampering, and medical science in general, within a society that values the superficial dictates of success and beauty over individual foibles and idiosyncrasies. In this age of reality-show plastic surgery makeovers, stomach stapling, and pills that address deficiencies of aesthetics rather than health, is there any question as to whether some individuals would scramble to embrace genetic modification in the name of beauty? There is a line between the laudable advances in medical science that save lives and enhance living, and abusing such advances. This line is one which a culture like ours, ruled by small-minded standards of worth and importance, is all too ready to cross. Slow and mournful, this story is presented as a sampling of memories and introspective musings by Denny’s father. Although the theme and subject matter presented are hardly unexplored in the realm of science fiction, Casil’s masterful handling of characterization is evocative and emotion-laden.

This issue of F&SF, with perhaps the exception of Matthew Corradi’s novelette, offers little in the way of original ideas or innovative concepts. But it delivers solid and enjoyable tales, well-written and well-told, that excel in powerful and frequently poignant characterization.