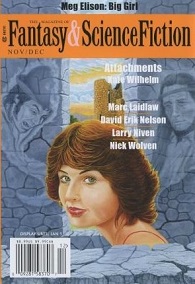

Fantasy & Science Fiction, November/December 2017

Fantasy & Science Fiction, November/December 2017

“Stillborne” by Marc Laidlaw

Reviewed by C. D. Lewis

The November/December issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction this year presents original fiction from nine authors. They’re varied in setting, voice, and theme and offer something for anyone interested in fantasy and science fiction. In the latest issue, here’s what you get:

Marc Laidlaw’s 19,000-word novella “Stillborne” continues a series depicting the fantasy adventures of Gorlen the bard and Spar, the gargoyle whose hand he was cursed to exchange with his own. Like the prior installment from Fantasy & Science Fiction’s April-May 2014 issue, “Sillborne” is set in the company of religious leaders whose values and priorities are calculated to entertain (both the primary story arc, and the background flashback). Makers of distilled spirits (and their marketing campaigns) also get a turn before Laidlaw’s gunsights typewriter. Humor is definitely the story’s greatest strength, and it is on display best when Laidlaw pens conversation between Gorlen and his rediscovered lover.

Unlike suave AI autos of yesterfiction in the tradition of Knight Rider’s K.I.T.T., the eponymous vehicle featured in Nick Wolven’s novelette “Carbo” is a run-down auto whose lowbrow AI has a penchant for leering at young women. And, having stalked them, a habit of plastering photoshopped snapshots of them on the windshield to draw upon its driver the righteous fury of its victims. “Carbo” recounts the descent of a perfectly ordinary AI car: maturing with a teen boy only to be lured by a drug-dealing college coder within range of lawless Mexican hackers south of the border and set loose on the streets (and sidewalks) of North (and Central) America. Zowie. Science Fiction is supposed–among other things–to warn us of the future. Here, Wolven entertainingly explains how a mash-up between your car and your cellphone produces, in the age of cloud backups, an undying SF version of Christine. It’s equally an indictment of customer-tracking technologies and the Wild West of privacy (non-)regulation. Also, it’s a fun story of a mother-son car repair job. Definitely to be read. But do it safely–get a paper copy.

R.S. Benedict’s “Water God’s Dog” is a tragic secondary-world fantasy that follows a faithful servant of Ganba, God of Water, in a place so long subject to drought that many refuse to believe rain exists. The first-person point of view gives an intimate feel to the narrator’s perception of his god’s urges, and the feelings that follow his efforts to sate the god’s whims. The narrator’s true-believer outlook and the fact his god produces concrete miracles when his demands are met make Benedict’s world interesting to inhabit: what does the god want this time, and where will it take the characters? Without ever coming out and criticizing the god or its servants, Benedict’s characters raise the question why (other than selfishness or fear) anyone does the god’s bidding, and why (other than perhaps a bullying nature) the god establishes the kind of relationship it does with its subjects. What must the god assume about its power to get what it wants from humans? This, of course, brings us to the tragedy: “Water God’s Dog” is tragic not in the plane-wreck-on-the-news sense but in the classic sense of a protagonist whose own virtue destroys him. The water god’s dog never questions its master, cannot think for himself, and has no power to improve the lives of those in his community. He is as much a parasite as the water god himself. Benedict takes a certain risk in penning an oblivious narrator who doesn’t understand he’s the problem—and whose inability to make decisions without the compulsion of his god doom him (and maybe, too, his god). Sure, he’s imaginative when he labors to interpret the whims of his impatient god, but what about for himself or his family? It’s interesting throughout, and not the story we expect. Definitely to read.

“Attachments” by Kate Wilhelm follows a woman who finds freeing herself from a haunting ghost as much a problem as freeing herself from a controlling, abusive ex. Disturbingly, some of the ghosts have motives like those of her ex. Wilhelm seemingly credits misogynist jerks with more humanity than does the reviewer, which though charming feels dissonant, and raises questions whether her more civilized-looking characters will turn out to conceal hidden depths of bitter vitriol. A cast of characters willing to threaten awful things to make their daydreams real puts the protagonist in real peril from all quarters. Wilhelm builds a sympathetic character, creates a host of physical and emotional threats, shows her thinking her way free. It’s a short fun journey.

Ingrid Garcia’s “Racing the Rings of Saturn” is an SF novelette set in the future’s most-watched, most-dangerous race, in which (as eventually develops) everyone involved is confident they’ve got the race fixed in their favor. Multiple plot threads break up the fast-feeling race sequence, which seems to exert a slowing influence … until they begin revealing the stakes in the race. Garcia uses the multiple threads masterfully, colliding them beautifully to reveal the grand plan. If you like racing, high-tech gizmos, high-stakes competitions, revolution, nudity, or dedication in the quest for personal enlightenment, this may be for you. Although it’d be tempting to discuss details, one would risk spoilers. One can safely say that it’s a short piece (for a novelette) for delivering so much zing, and definitely not to be missed.

In “Big Girl” Meg Elison depicts the reactions of others to a youth’s overnight transformation into a 350-foot colossus who is a 15-year-old girl no clothing can fit, then follows her equally-unexplained but years-long slide into tiny-ness. The wildly inaccurate news reports, the we-hardly-need-an-excuse-to-transform-her-into-a-sex-object Internet response, the confused and contradictory statements from different government agencies, and the response of her powerless family all have a plausible feel—some amusing, others disgusting. The decisions depicted in the piece are chiefly those of third parties: the youth herself seems hardly to make a decision, even as she inadvertently tears the arm off a man she catches trying to take indecent photographs while she sleeps. She does make a decision to flee and to return, but those are hardly the stuff of story climaxes. The real point of the story seems to be that the world around the young woman continuously makes judgments about her, without her having to take any action at all to invite it: she need only be noticed to be subject to the judgment of an unlimited number of strangers who declare themselves authorities competent to declare what she is or means. She has no control at all over the rules in which those judgments are grounded or the (in)justice of the positions taken by those who decide they have the authority to comment on her. In apparent imitation of the story’s point, Elison depicts her shrinking until she vanishes entirely. It’s a downbeat piece, not a story in the sense of having a plot arc with character-revealing decisions, but a series of snapshots depicting a world so awful and dehumanizing one easily understands the main character’s decision to flee it. As a piece designed to get a reaction, it succeeds: it evokes feelings, for sure. They’re just not pleasant. And that, surely, was Elison’s point all along.

Larry Niven’s “By the Red Giant’s Light” is a short story about two characters who spend what turns out to be more than an ordinary human lifetime responding to a danger to the last human (albeit rather modified) in the solar system. It’s set at a time the Sun’s expanding diameter has engulfed Mercury’s orbit. The initial hook—the difficulty of telling the human from the robot from their exteriors—gets us into the story’s heart, which is the human’s plea for help against an asteroid due to destroy Pluto and, with it, the last intelligent life in the solar system. There’s some fun SF detail—information so long unused and unexpected to be used turns out to be valuable, but can it be recovered from a finite data storage subject to periodic pruning, the value of experience to a character with longevity that outlives civilizations, nonhuman values and reasoning driving the protagonist to un-neighborly measures. Although the story is told in third person, it’s a close-third over the shoulder of the human. Since we empathize with the human and the stakes are death, it doesn’t feel like the story’s big decision (to choose the course of action calculated to lead to survival) is difficult: we’re not presented with any other options that lead to survival. The story’s strength is therefore more in the realm of competence porn than character development. Although not difficult, the protagonist’s decision is character-defining—she’s a survivor, and chooses accordingly. There’s just little anticipation in the choice because it seems the decision presents little challenge to her values. The challenge, rather, lies in executing the plan and living with the consequences: bad relations with the only neighbor on the planet. Competence porn with consequences for character choices makes it solid SF, worth reading, and reminds us why we’ve loved Niven for decades.

“Marley and Marley” by J. R. Dawson is a time-travel drama about a woman who’s lost everything, sent into the past to raise her orphaned 12-year-old self to the age of 18 because the social services people in the time-cop business think it’s a better deal than sending the young girl into the foster system. It opens dark: the girl found her mother having hanged herself, and the adult lost her husband in a senseless accident. But since the time cop folks gave dire warnings about fooling with the future, and required the adult to memorize people off a list of VIPs with whom they must interact exactly as they did the original time they met, there’s a sense nothing can be improved from the status quo. Details offer an undercurrent of hope: the protagonist as a sent-back-in-time adult meets a future President working as a teenage grocery checker. Circumstances can change. But as Marley learns from Marley, change takes courage. Anyone who’s ever watched a fearless youth crushed by life into a cowardly rules-follower—or fights this force personally—will enjoy this reminder we hold the power to change the world.

Readers who twitch at time loops and paradoxes need to be ready to roll with it a bit. This isn’t hard SF, but you’re allowed to love feel-good tales about people taking control of their lives and improving their circumstances. Curiously, the story never addresses the “you’re a nobody” impression the time cops leave on Marley when she’s sent back in time and ordered not to monkey with the VIPs. As a reader, once I saw changes creep in I began to expect the whole purpose of sending Marley back in time to raise herself was to form a universe-changing super-person who could emerge only as a result of the iterative process of knowing how a parenting choice impacted her so she could tweak it toward improvement when it came her turn to parent. Imagine having the chance to correct parenting errors until you’d done it right. Like Groundhog Day, the story’s premise allows a time period to be tweaked until it’s perfect, no? The warm ending is a soothing balm to the story opening’s cold, sandpapery relationships. Change is good.

“Whatever Comes After Calcutta” by David Erik Nelson tells the story of a defense attorney who doesn’t seem to feel much about his work or life. It’s as if he’d turned off. Nelson tells the story of the day he found something he felt like doing. The more of the legal nuttiness being peddled by tax scheme promoters and anti-government nuts you understand—bogus Constitutional claims and utterly-made-up processes that misstate the purpose and effect of the Uniform Commercial Code—the richer the hicks will feel. They offer some rich stuff: too deeply lost in malarkey even to talk to intelligibly. Or … are they? Just because you stop a witch execution doesn’t mean you’ve figured out who the nuts are. The piece’s strength is its unexpected point of view, and the transformations the protagonist takes as his day gets weirder. But things definitely end on a high note: he’s got something to look forward to, now…

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.