“I am the Whistler, and I know many things, for I walk by night. I know many strange tales, hidden in the hearts of men and women who have stepped into the shadows. Yes… I know the nameless terrors of which they dare not speak.”

“I am the Whistler, and I know many things, for I walk by night. I know many strange tales, hidden in the hearts of men and women who have stepped into the shadows. Yes… I know the nameless terrors of which they dare not speak.”

The Whistler (May 16, 1942-September 22, 1955) aired “Harvest of Death on November 5, 1945. There were two attempts to break into the east coast market that didn’t last long (July-September 1946, and March 1947-September 1948) due to mediocre ratings, so if these episodes are counted as part of the overall scheme of things, the total number of shows ends up somewhere around 769. Over its thirteen-year west coast run it never took a summer break and ran continuously, certainly some kind of record, and its sole west coast sponsor, Signal Gas & Oil remained loyal throughout. While the show had several narrators over the years, the one who held the longest tenure and is most associated with the show was Bill Forman.

The Whistler has an interesting backstory, and would take much too long to go into here to give it the justice it warrants. A few points of interest will suffice for this offering of the beloved mystery show, the first of which is the use of the narrator as more than just a host. From Jim Ramsburg’s Gold Time Radio entry on The Whistler: “Like The Shadow’s first personification a dozen years earlier, Inner Sanctum’s ghostly Raymond in 1941 and The Mysterious Traveler in 1943, The Whistler stood outside the stories he narrated. Unlike the others, he used a unique second-person, present tense technique as if to talk directly with the central character of his stories – often an innocent drawn into the plot by circumstances or an amateur driven to murder as a last resort.” A second point of interest has to do with the trademark whistling that opens each episode. From Radio Spirits‘ Blog Archive on The Whistler: “The program featured one of radio’s classic openings: a haunting 13-note theme created by Wilbur Hatch (who also composed the show’s eerie mood music). Hatch estimated that only one person in twenty could whistle this exact melody, and for the show’s thirteen-year duration one person pretty much did—a young woman named Dorothy Roberts. In fact, during the war years, Roberts had to get permission from Lockheed (where she worked) to leave her factory job in order to make it to the program and whistle every week.”

The radio show proved popular enough that Columbia Pictures made eight Whistler films from 1944-48, all but one starring Richard Dix: The Whistler (1944), The Mark of the Whistler (1944), The Power of the Whistler (1945), The Voice of the Whistler (1945), Mysterious Intruder (1946), The Secret of the Whistler (1946), The Thirteenth Hour (1947) and The Return of the Whistler (1948). The show was brought to early television in 1954-55, but never caught on. Nevertheless (and due in great measure to roughly 500 of the estimated 700+ original shows still surviving–and the movies still showing up on classic movie tv channels), The Whistler probably enjoys a larger audience today than it did in its heyday during the Golden Age of Radio.

“Harvest of Death,” as you will hear from the enthusiastic sponsor about halfway through the episode, is touted as being the show’s 100th episode. It deals with a farmer, his wife, and their farmhand. The farmer is a crass, suspicious, and spiteful fellow toward his wife, who he believes pays more attention to their long-time farmhand than she does him. For her part, she denies it, but as the story progresses–and whether she speaks truth or not–her voice is enough to make one take a hatchet to her (see if you agree). Several plot twists propel the story, and as always with an episode of The Whistler, there is a final zinger twist at the very end. This episode is noteworthy more for the character change in the shrewish wife (the actress does a remarkable job of making listeners hate her guts), than almost anything–outside of the final twist. Kudos to the writer for taking the listener on an emotional ride as our sympathy wavers from one character to the next, and again to the actress for giving life to the dialogue she was given, and which provided the foundation for her crazy character, and ultimately rewarding performance.

Play Time: 30:00

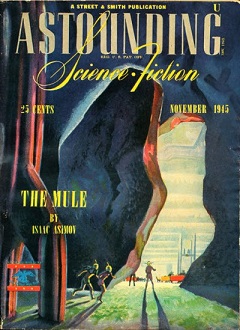

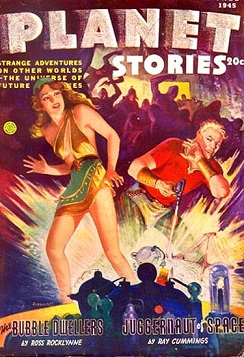

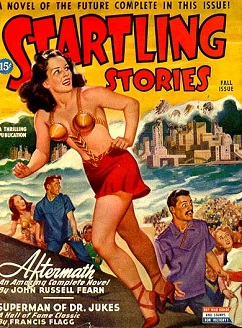

{November of 1945 found the neighborhood gang looking forward to Thanksgiving break from school. It would be their respective families first Thanksgiving with the country at peace since VJ day had ended World War II a few months earlier. It was a happy time for the country and for our faithful SF pulp magazine fans.The corner newsstand was brimming with colorful magazine covers, but for this visit their choices were easy. Astounding SF (1930-present, now Analog) was a no-brainer, and this issue was no exception, for it featured what was to become one of Isaac Asimov’s more famous stories from his Foundation series, “The Mule.” Planet Stories (1939-55) and Startling Stories (1939-55) were both quarterly publications in 1945, and though lower paying markets than the monthly Astounding, nevertheless provided young imaginations with wonderful stories of adventure and peril, many on other worlds, and more often than not ran stories by the major names in the field.}

[Left:Astounding, Nov. 1945 – Center: Planet Stories, Fall 1945 Right: Startling Stories, Fall 1945]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.