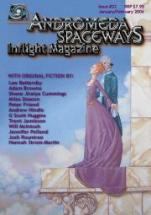

“Blake the God” by Lee Battersby

“Marco’s Tooth” by Trent Jamieson

“The Last Cyberpunk” by Will McIntosh

“It’s Only Rock and Roll” by Hannah Strom-Martin

“Mail Chauvinism” by G Scott Huggins

“Black Box” by Miles Deacon

“Western Front, 1914" by Peter Friend

“Tiny Sapphire & the Big Bad Virus” by Josh Rountree

“The Once and Future Creepy” by Andrew Hindle

“Love in the Land of The Dead” by Shane Jiraiya Cummings

“MarsSickGirl” (reprinted) by Jennifer Pelland

ASIM veteran Lee Battersby gives us another story of godhood, “Blake the God.” The deity in question is our protagonist’s nine-year-old hyperactive stepson. One day, Blake and his stepfather (Jim) notice that their patio has been torn apart, the bricks rearranged to form an uncanny replica of Blake’s face. Stranger still, the sculpture changes to match Blake’s shifting facial expressions. The who, how, and why of this odd setup are soon revealed; suffice it to say Battersby packs a few enjoyable surprises into this short story. Best of all are Jim’s and Blake’s nonchalant attitude towards the day’s events, contrasted with their anxiety over Mom’s imminent return home. Battersby’s humor derives from an understanding of his characters and of human nature. The result is effortless-appearing comedy, free of forced jokes and flat gags.

Trent Jamieson’s “Marco’s Tooth” is a revenge tale that strives for significance and poignancy but falls regrettably short. Simon, a priest, travels to Styron at the summons of Marco, a former dictator responsible for many great and horrible acts. Simon has vengeance in mind, as Marco’s soldiers killed Simon’s sister. But things are not as they seem, and Simon must come to terms with some surprising truths about his own existence. The story’s setting—an ancient alien artifact, a massive, gravity-defying stone “tooth”—is interesting, but does not play as much of a role in the denouement as I expected it to. I found I had little empathy or sympathy for Simon, less still for Marco or his aide, Galley. “Marco’s Tooth” feels like a big story crammed into a small format. It misses the mark due to a lack of adequate character development.

As the title suggests, Will McIntosh’s “The Last Cyberpunk” envisions a cyberpunk master pitted against a post-cyberpunk world. Bruce, the story’s protagonist, is an old man, and he’s tired of burying friends like Neal, “one of the greatest cyber-architects who ever lived.” The names are intentional—Bruce, Neal, their friend Bill. Their virtual world, Bit-Town, is usually deserted, or worse, vandalized by retro-freaks with no respect for Bit-Town’s consensual etiquette.

Bruce’s attachment to outdated technology and his horror for the new organic technology make for a surprisingly touching story. If we define ourselves by our technology, what happens when new technology leaves us behind? McIntosh treats this question with sensitivity and insight, but this story is not a dry exploration of a theme. McIntosh’s late 21st-century world comes to life thanks to some vivid (if revolting) details. For such a brief tale, McIntosh accomplishes much, and with great technical proficiency.

Hannah Strom-Martin’s “It’s Only Rock and Roll” is an imaginative blend of faery-world fantasy and hard rock jams. Eradia, better known as Gwyllion among her fellow immortals, is lead singer for Beautiful Pornography. All she wants is to play her music and live as mortals do—mortals with lots and lots of groupies, naturally. But her mother, the faerie queen, has other plans for Gwyllion. Strom-Martin’s playfulness and sharp sense of humor reminded me (in a good way) of Adrienne Jones’s Gypsies Stole My Tequila, which I reviewed here a while ago. As with Jones’s story, Strom-Martin takes a familiar setup and infuses it with personality, making it her own unique world. I have only one quibble: a few spelling and punctuation errors slipped past the editor on this one.

A futuristic bookseller (a “Combat Retailer”) does battle with an unruly thirteen-year-old boy in G. Scott Huggins’s “Mail Chauvinism.” Once he gets rolling, Huggins delivers a funny, twisty story which should amuse anyone who has to deal with customers, and particularly their kids, on a regular basis. Unfortunately, the opening required all of my patience, packed as it was with acronyms trying too hard to be jokes. When I came to a paragraph full of capitalized words and found myself trying to parse out the acronyms rather than paying attention to the story, my will to continue nearly failed. That would have been a shame, since the story proper is a hoot.

Miles Deacon’s “Black Box” is the stuff of nightmares. A deep space company worker awakens to find himself suited up and adrift, with no ability to communicate with his coworkers. He takes it all in stride, refusing to panic, and does everything by the book. Eventually, he realizes that his calm, measured responses are far from sufficient.

Deacon’s workaday sensibility brings to mind Stanislaw Lem’s Pirx the Pilot stories, but Deacon writes like Lem’s darker half. This is one creepy, chilling story, certainly one of the best in this issue, and one of the best stories I’ve read this year. The terror lies not in any Alien-style monster, but in the reader’s slowly growing understanding of what the company will do to keep its employees alive—and why they care so much.

There’s no shortage of imagination in Peter Friend’s “Western Front, 1914.” Professional virgins, marauding monsters, and young Private Adolf Hitler as a forensic artist: this doesn’t reveal half the secrets of Friend’s brief but delightful short story. Calling it brief doesn’t do it justice, however. “Western Front, 1914” is so admirably tight, twists and surprises seem to occur with every other paragraph. The ending packed the best (and funniest) surprise of all.

“Tiny Sapphire and the Big Bad Virus” is Josh Rountree’s cute cyberpunk retelling of Little Red Riding Hood. “Cute” is the operative word here. I found myself smiling through much of Rountree’s story, even though it was ploddingly predictable. More often than not, cyberpunk takes itself too seriously, so a bit of fun like this is a good thing indeed.

Andrew Hindle’s “The Once and Future Creepy” chronicles the time-traveling adventures of Hatboy, his roommate Creepy, Future-Hatboy, and Future-Creepy. Hindle has an excellent grasp on annoying housemates, so most of the sharper humor derives from Creepy’s and Future-Creepy’s incredibly annoying geekiness. The story runs on dialog, however, and most scenes are grounded with scant few words of description. After a while, the effect is bewildering, particularly given Hindle’s goal of squeezing jokes from temporal paradoxes.

“Love in the Land of the Dead” by Shane Jiraiya Cummings is an ultra-short zombie story with one hell of an opening line. Unfortunately, the rest of the story didn’t live up to the promise of that first line. Nothing worked for me on this one, neither the humor nor the story.

In the world of Jennifer Pelland’s “MarsSickGirl,” dreams are recorded and uploaded to the freenet, where others can download and experience them for themselves. Vienna Andrade is an unemployed graduate of Galileo University on the Jovian moon Callisto. She’s a Mars native who would love to get back home, but her money and options are running out. When her dreams hit big on the freenet—dreams of violent revolution against Earth-born colonists, and the Earth-controlled megacorps who dominate the Martian and Jovian colonies—she’s approached by a megacorp that wishes to buy her dreams and market them to the very people she dreams of overthrowing.

Will Vienna sell out to DreamWeaveCorp? If she does, will she ever be able to regain her self-respect? Pelland delivers on this promising setup. She has done a fine job of world-building and of creating a sympathetic character in Vienna. There is a patch of dry storytelling towards the end, but the conclusion itself is believable and satisfying.

[Editor’s Note: ASIM is offering this issue as a PDF download for AUD$3.00 (Approx $2.00 US) as part of an e-version trial.]