“War Profiteering” by M. Darusha Wehm

Reviewed by Brandon Nolta

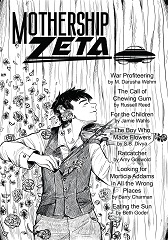

What makes a story fun? That may seem like a silly question—or a profound one, depending on how seriously you take it—but the writers gathered in the latest issue of Mothership Zeta illustrate the fact that fun is a very subjective concept, with a panoply of tales that range from wacky to poignant.

With “War Profiteering,” M. Darusha Wehm gives us a sales pitch for the handy-dandy Missionwhisper Orangescan™ Nanoparticle Detection, Inspection, and Extraction Unit, or MONDIEU if you’re nasty. Truly a miracle device for the cleansing and reconstruction of food, the MONDIEU is indeed a lifesaver…for some entities, that is. Wehm does a solid job of mimicking the breathless tone of infomercials and annoying sales ads, even when the product description starts to lean away from kitchen aid and more toward doomsday device. Wehm’s tale is a slight piece of straight-faced drollery, but a fine start to the issue.

For a good outright laugh or six, readers can head directly to Russell Reed’s “The Call of Chewing Gum” and follow the adventures of one Mr. Huxley, who has recently inherited a house full of old documents, ancient tomes, odd statuary, and many references to an Elder God with a ridiculous name. As readers of Lovecraft would expect, many unusual discoveries and portents await Mr. Huxley, but he can’t be bothered with any of them, because he’s trying to make a love connection with his therapist. Readers who can respect what Howard Philip brought to the field while simultaneously bemoaning some of his more overwrought passages will appreciate what Reed achieves here with his deft undercutting of the Cthulhu Mythos.

In “For the Children,” Jamie Wahls takes us to a civilization ship tooling merrily through space, although it’s more of a flying hard drive. Humanity has mostly gone digital and exists in a massive bank of storage modules, living out any number of existences in computer time. Somebody has to mind the physical world, however, which is where Riva, the story’s protagonist, comes in. Inconveniently killed at the beginning of Wahls’ tale by a hull rupture, she uploads into another body to get the ship repaired and keep the mission going, eventually summoning a companion from the teeming simulated masses to help. Along the way, Wahls gently leads the reader through witty exchanges and good-natured workplace grumbling into a subtle rumination on the nature of humanity, with an aside or two about how immortality might affect a species. Thoughtful, but light on its feet.

Not all superpowers are equal, but then again, maybe it’s just in how they’re used, as S.B. Divya’s charming “The Boy Who Made Flowers” shows us. Charlie Kim, like many kids his age, is hoping he gets a cool superpower when his finally manifests. Unfortunately, the power he gets—spontaneous flower generation, based on his mood—isn’t what he was hoping for, and being different in such an obvious way doesn’t make his life easier. Still, Charlie’s support system is good, and before too long, he finds a way to make his newfound gift work for him. Sweet without being cloying, Divya’s narrative captures the discomfort and roller-coaster emotions of puberty, and delivers a realistic but upbeat conclusion that caps Charlie’s tale nicely.

Airships, World War I, and sabotage by the restless dead: Amy Griswold’s “Ratcatcher” puts a paranormal spin on the Great War to good effect. Xavier is a ratcatcher, whose duty is to clear out the souls of the dead from, and prevent ectoplasmic vandalism against, the troops and materiel of the English armed forces, armed with ghost traps and a shattergun, a weapon that destroys souls. Due to a near-miss from a shattergun round, his own soul was destroyed, and his continued existence depends on keeping the soul of another soldier caught in a trap merged with his body. When the story begins, Xavier is haunted not just by the lost soldier’s soul, but by his own fear of dying, but advances in ratcatcher tech soon introduce a possibility that Xavier finds worse than death. Griswold’s story isn’t “fun” in the same sense that its predecessors are, but the plot moves swiftly and well, and Griswold builds a believably rich world and protagonist with concision and conviction. In an issue stuffed with excellent work, Griswold’s story stands out as the most accomplished of the bunch.

Love doesn’t die just because you did, Barry Charman argues in “Looking for Morticia Addams in All the Wrong Places,” a warmly good-natured riff on romance with a vampire. Alan, a creature of the night, has just been thrown out of his home by his longtime paramour Scarecrow, and while wandering around, runs into a sweet mortal woman, Ruth. In this world, vampires and other denizens of the night are well known and understood, but despite this, Ruth finds herself drawn to Alan, and he to her. So begins a courtship that only occasionally runs into downsides like a swarm of revenants, and Charman acknowledges the troubles that each faces with the other, while underlining the reasons they work together. Romantic without being fuzzy-headed, and mixed with just the right combination of spiky wit and death, Charman’s tale shines.

Finally, Beth Goder closes out the issue with a lyrical look at creatures vaster than empires called “Eating the Sun.” Aelegan, an eight-limbed suneater, is preparing for a long trip to another system so she can take part in an ascension ritual and move up to another level of existence. Before Aelegan can go, however, she needs to fuel up, and the star of the 83rd system from Prime looks like just the ticket. However, the sun has other ideas, and how the suneater and sun resolve their differences over poetry and mercy forms the basis of Goder’s poignantly lovely tale, which closes out the collection with grace and warmth.

Mothership Zeta #4, July 2016

Mothership Zeta #4, July 2016