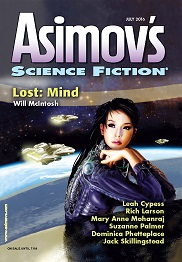

Asimov’s, July 2016

Asimov’s, July 2016

“Ten Poems for the Mossums, One for the Man” by Suzanne Palmer

Reviewed by Chuck Rothman

July’s Asimov’s begins with “Ten Poems for the Mossums, One for the Man” by Suzanne Palmer and starts out with a protagonist — a poet — attending what is essentially a writing retreat alone on an alien world with strange life forms, including the Mossums, described as “green fuzzy boulders.” The poet writes a series of poems about his impressions, and slowly begins to discover that the Mossums are more complex than he imagines. The story started a bit slowly, but quickly drew me in, and it was nice to read something that portrayed aliens by hints and without any clear-cut answers.

Leah Cypress‘s “Filtered” is an astute extrapolation at how the web and Facebook are affecting us all. Steve is a reporter who has stumbled onto an important story, but is stymied by his editor Margie (also his wife). In the near future, all news has to go through filters that automatically determine who will be interested in them, and if the story doesn’t match enough people’s interest, it never gets out. Steve works to find a way to get the story out. I found, though, that the story leans far too much on the futile end of things; depressing and offering no way out. The metaphor is a good one as people even today are picking and choosing news that matches their worldview, but the answer here it too bleak and the characters just accept it in order to work on their own problems.

“Masked” shows a future where the wealthy use both makeup and holographic techniques to make themselves as beautiful as they can. Bess is about to meet again with her friend Vera, who has suffered a computer virus that wreaked havoc with the computer programs she uses to adjust her appearance. Vera is supposedly recovered, but Bess can see that she doesn’t seem right. Rich Larson‘s version of the future and the styles are well imagined, and one of the strengths of the story is the way that Bess begins to understand what’s really important.

“Project Entropy” by Dominica Phetteplace follows Angelina, a woman who is returning to work after a malfunctioning computer chip had put her into the hospital. Angelina goes about her recovery — the chip allowed her to remember things about the people she dealt with in her job — and discovers a minor revelation. The story reads as though it were the middle chapter of a novel, one that comes between the interesting parts. What happened before and after sounds far more intriguing that what we see here, with is pretty futuristically mundane with a lot of padding.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: an inventor creates a method to solve the problems of mankind, looses it on the world, and discovers there are Drawbacks (in ironic reversal of what the inventor wants). “The Savoir Virus” by Jack Skillingstead fits this mold perfectly. After a bombing, John Crawford designs a virus to eliminate peoples’ belief in God. The story consists of various philosophical discussions and, to be fair, they are interesting to read. But I was put off by the predictability of the thing and the revelation at the end seems like something that was obvious from the start.

Robert Thurston‘s “Nobody Like Josh” is a character study, a look at the long-time high school handyman who happens to be an alien. The narrator has been a student, teacher, and administrator of the school and talks about how Josh had interacted with him, and with the others over the years. There’s very little plot, but that doesn’t matter. The joy of the story is seeing Josh and how he is alien and still, in many ways, very human.

“Webs” by Mary Anne Mohanraj deals with the issues of how enhanced humans are treated in a future society. Anna is caught in the middle when three of her neighbors show up at her door, terrified that they would be the victims of a riot that is headed toward them. The friends — Javier, Katya, and their daughter Sara — are gliders, humans who have been changed so that they can fly in air currents, and are targets for the mob. The story flirts with futility before coming up with a pyrrhic win. However, the concept has been around a long time, and does seem overly familiar.

The set up to Will McIntosh‘s “Lost:Mind” is convoluted, but once that’s past it becomes a fine story. Colonel Walter Murphy’s wife Mimi is dying of Alzheimer’s and, desperate, he turns to technology, creating a recording of her mind so she can live on. But such experimentation is illegal in the US, so it has to be smuggled in from India. A full mind would raise alarms, so it’s broken into 32 pieces of a chess set, to be assembled later. And the chess set is stolen. What follows is a race against the clock to find the pieces (from a noted sculptor) before the battery dies, along with Mimi’s mind. There’s a great mixture of action, dead ends, and emotional roller coasters to make the story one of the best of the year.

One thing about reviewing Asimov’s: even when I don’t care for a story, I’m still engaged enough not to have to force myself to finish it to review. These are all excellent stories with plenty of good reading.

Chuck Rothman’s novels Staroamer’s Fate and Syron’s Fate are available from Fantastic Books.