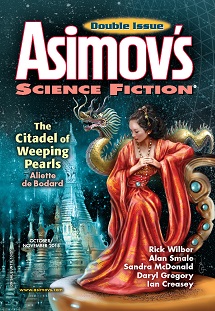

Asimov’s, October/November 2015

Asimov’s, October/November 2015

Reviewed by Colleen Chen

I very much enjoyed this issue of Asimov’s, which features one novella, four novelettes, and four short stories. As usual, the variety is good in terms of light vs. heavy fare and across the range of SFF (plus a couple of ghost stories), and the writing is superb. I noticed a lot of strong female characters in this issue, with a variety of ways that that strength is expressed—it reminded me of a quote I read recently about how the more you read, the better you understand others’ emotions. This is a good issue for vicariously experiencing a range of emotion.

“The Citadel of Weeping Pearls” by Aliette de Bodard is the lone novella of the issue. It explores a fascinating future world in which the Empress Mi Hiep, in Dai Viet space, is dealing with potential war with the Nam Federation, who threatens them with both new ships that are as good as or better than the Viet intelligent mindships, as well as an ability to hijack mindships.

The story begins with the discovery of the disappearance of Bach Cuc, who was on the trail of the Citadel of Weeping Pearls, a refuge for the empress’ eldest daughter, Bright Princess Ngoc Minh. Thirty years ago, Ngoc Minh had quarreled with her mother, and when her mother sent the Imperial Armies to destroy the Citadel, it had vanished overnight with everyone onboard. Bach Cuc sought the Citadel in deep spaces—places where time flowed at a different rate, making the past accessible, and she thought she was close to finding it.

The story explores various points of view—the empress, that of two citizens who have built a time machine that can bring them back thirty years ago to when the Citadel still existed, the general who tries to solve the mystery of Bach Cuc’s disappearance, the passive younger daughter of the empress who is rife with internal conflict about her disappeared sister and her own place in the Dai Viet hierarchy.

Once I got past the confusion of associating names with characters—for there are a lot of characters in this story—I got really into it. It made me think of the Vietnamese soap operas my parents are addicted to, not only for the cultural tie-in, but for the air of tension and burgeoning tragedy that underlies each scene and the poignant emotion that falls short of melodrama entirely because the writing is so skillful. The world-building in this story is superb. I became increasingly enthralled as I read up until the final ominous finish—for yes, I have to admit that I hate the sort of poetically just ending as de Bodard gives this story, although it’s entirely appropriate. The story’s message is that there are no miracles—but there are some darn well-written stories, and this is one of them.

The first of the novelettes is “English Wildlife,” by Alan Smale. In it, Richard has taken his girlfriend Corinne on a tour of his native country of England, and their relationship is being strained both by Corinne’s obsession with English history, and by the obsession every English male they meet has with Corinne. The conflict between Richard and Corinne comes to a head after a visit to a church with a number of Green Men sculptures—rumored to be pagan symbols, but which hint at a possible relevance to present time. Corinne disappears after an argument, and Richard is torn between the obvious explanation—that she has had enough of him and is leaving him like he always feared she would—and a feeling that there is a deeper mystery behind her disappearance, one that is tied to the Green Men.

“English Wildlife” features a strong female character—one who is stronger in some ways than the man who loves her—and a man with obvious flaws who tries in his way to prove his love. The story bears a fascinating and complex mix of history, folklore, spirituality, and the psychology of human relationships. It was occasionally difficult to follow, but that might be because the tension was drawn out so effectively that I read faster than I should have. I enjoyed the setting as well as the growth of the characters before a backdrop of a strange and fixed annual cultural tradition.

“The Hard Woman” by Ian McDowell also features a strong female, but in this case the story is from her point of view. It takes place in the city of Tombstone in the Old West and includes the Earp Brothers as supporting characters. Known as “Cecile Sans Peur, the Bullet-Proof Frenchie,” the heroine is a 30-year-old woman with the ability to make her flesh hard enough that it withstands any bullet, knife thrust, or other attempt to penetrate her skin. She’s on a mission to kill George Bass, the man who killed her lover. She’s strong, but she’s not entirely invulnerable, as we discover when she finds him.

This is a unique and satisfying tale, more sensual than the usual SFF fare, and easily bridging other genres—it’s a Western, it’s a romance, it’s a comedy and a bit of a yarn. Cecile is a great protagonist—she’s resilient, smart, and passionate, and she takes the law into her own hands because she knows that no retribution will be delivered unless she does it herself. Despite her strength, her vulnerabilities are obvious, so as a reader I got to have the vicarious experience of both her power and her fear. It was better than a roller coaster ride and left a great aftertaste.

“Walking to Boston” by Rick Wilber begins with Harry visiting his wife Niamh at the nursing home. She lives in a senile haze, mostly in the past, and recently her mind has been back in the war years when Harry’s plane crash-landed in Ireland and they met. On this particular visit, she’s talking about visiting her sisters in Boston, and although she has no sisters, Harry humor her desire to go out and they begin to drive.

Something odd happens on the way. Harry begins to see things as they were in the past; he swears the car they’re in is the Buick they bought after the war, and the places they visit are in the past, with prices to match. Sometimes they slip back in the present, but for the most part Harry continues with the dreamlike flow of a road trip that is happening as if they were living in those post-war years. We learn that he wasn’t such a good husband, that there were numerous affairs. We also hear the story of the crash as told from Niamh’s point of view, and we learn of something strange about that crash—Niamh was a local Irish girl, after all, with a relationship with the sea-creature sisters called selkies. We learn that the selkies may have played a part in the aftermath of crash—and that there is a debt to pay, even after all these years.

This is a surreal story, mostly dreamlike but with an underlying tension that had me feeling a little nervous throughout the read. It was hard to get a “fix” on any character or aspect of the story—Harry is likable, but sometimes not, and Niamh is an innocent victim, and then maybe not. It’s hard to judge anyone in the story—yet certain aspects beyond the problems in the marriage that were admittedly Harry’s fault controlled an inexorable outcome. Interesting story, to be sure, with strong details that kept me traveling along with them and cognizant of the flavor of the different time periods described. The scene of the crash is pretty amazing. I don’t think I can say I liked the story on an emotional level, but it was definitely effective and well-crafted.

In “Begone,” by Daryl Gregory, the narrator is a once-successful businessman who’s been cast out of his family, home, and career. The story unfolds in a series of flashbacks interspersed with present time, gradually revealing that once he no longer fit his wife’s agenda of creating the perfect suburban life, she banished him using witchcraft. Like the typical tunnel-visioned jealous husband, instead of changing the things about himself that his wife doesn’t like, he plans to take back his old life by murdering his replacement. That works about as well as could be expected.

I haven’t watched TV in a while, but reading this story made me feel like I was watching a prime-time episode of a show about witches. The plot is over the top, the characters two-dimensional and stereotypical, the portrayal of witchcraft implausible. Despite all of this, the story is gripping and never stops being entertaining, the main character so sympathetic that we cheer him on despite his glaring flaws and lack of moral fiber. Also, beneath the flamboyant surface elements there is a very real and human story about husbands and wives and what they face when trying to work out their problems.

“The Adjunct Professor’s Guide to Life After Death” by Sandra McDonald is one of two ghost stories in this issue. It explores the question of what one might do to break free of ghosthood—a place where one is “wedged in the barrier between life and oblivion, flailing around in an eternal existential spasm.”

Lea Davis is the resident ghost of the 2nd floor of Building 2 on the college campus where she used to teach. She spends her time watching the students and the professors on campus, observing their secrets, their daily habits. She sees the adjunct professor who’s taken over her job, her classroom, and even the lover she had while alive—a married professor who was part of the reason why she committed suicide. Everything might have remained the same except other ghosts from a shooting in the library and subsequent fire start showing up; they are drawn by electromagnetic radiation leaking from the phone of the ex-lover-professor’s cellphone. Lea is bothered by the intrusion of other ghosts in her territory, but when Michael—the person responsible for the shootings—shows up, his incessant crying drives most of them away. Lea’s attempts to get Michael to stop crying causes her to start seeing what it is that traps people in ghosthood—and a possible way for her to free herself from it.

I loved this story. It’s timely—offering a commentary on both school shootings and on the dead-end aspects of adjunct professorships—and it’s philosophical, showing how the narrowness of how we perceive our lives can become a self-perpetuating prison. It’s hopeful and even a little bit romantic. The writing is lovely, humorous, and down to earth.

“With Folded RAM” by Brooks Peck plays off of the famous 1947 novelette, Jack Williamson’s “With Folded Hands,” about robots developed to protect humankind from harm that end up taking over all aspects of human life and lobotomizing anyone who resists. In this modern take on that theme, three insurgents are in a spaceship free-falling toward a space station orbiting Earth, on a difficult mission to break in. Within the spaceship are two men with an AI that’s gone critical; it’s busy overcoming the limits in its programming, baking brownies, and thinking up all sorts of ways to improve the human race. When the insurgents manage to infiltrate the space station, they have an encounter, and we get a lighthearted look at the now-common trope of disastrous consequences with too much power delegated to technology.

I have to admit that I hadn’t read Jack Williamson’s story before reading this one, and because of it I had to read “With Folded RAM” three times to get an idea of what was going on. I think it would do well as a short screenplay, as it has a lot of characters and is very visual. I found it amusing, the dialogue particularly clever. The snippets of information I could gather about the background for this universe were too abbreviated for me to get much of a feel for it; overall the story feels more like a joke with a punchline than anything else—and it’s a punchline much better understood if one is familiar with the story it’s playing off of.

“Hollywood After Ten” by Timons Esaias offers an interesting angle on time travel stories. A bunch of people in the future are being prepped to go back in time to try to change a specific event in history—in this instance they’re headed for a party in 1948, when McCarthyism and anti-Communist hysteria was in full throttle. The time travelers are attempting to gain support for the Hollywood Ten, who were blacklisted in Hollywood due to their beliefs, by making it appear that many people are willing to take a stand in their support. The story focuses more on the spectacle of the performance than on the possible impact of interference in the past; it’s a Hollywood experience in itself, the way the travelers have to learn the history, the lines, the daily practices of a long-gone era, and the way that intentions get lost in the commercialization of even something like trying to rectify a moral error in history.

The details make the story in this thought-provoking, complex tale. It’s a behind-the-scenes look at the rehearsal and the production of a scene, a Hollywood performance made to affect Hollywood. It doesn’t even seem to matter in the story whether the travelers succeed in changing the past through their actions. The rectification of the errors happens in the attempt to make a change.

In “My Time on Earth,” by Ian Creasey, a girl named Amy is telling a ghost story to her friends about her visit to Earth, a planet full of ghosts because so many people have died there (even more so than now, as this takes place in the future).

In Amy’s story, she goes on a ghost walk the night before she and her parents are due back on their spaceship. After that one-hour tour, she’s alone in her hotel room when she’s accosted by a ghostly apparition who says he’s anchored to the stone where his heart’s blood was spilled. Since he’s tired of being stuck there, he wants Amy to take the stone back to her planet. Amy agrees, but when she gets the stone and tries to get it into her suitcase along with her other souvenirs, it won’t fit. Her solution to the packing dilemma reveals unforeseen aspects of the ghost’s true nature.

Super fun story! The narrator is mischievous and creative and altogether endearing. I loved the dialogue, the storytelling format, the interaction with Amy’s audience, the several stories-within-the-story that all reveal aspects of Amy’s world—both how it’s different and how it’s the same as things are now. In the future, kids still fear ghosts and get the same thrills from the stories, just as much as I did from this read.