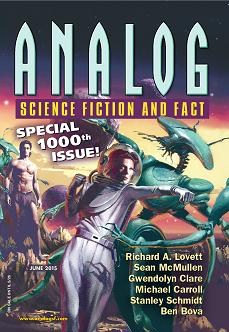

Analog, June 2015

Analog, June 2015

Reviewed by Colleen Chen

This month, Analog celebrates its 1000th issue–the most of any science fiction or fantasy magazine in history. Analog‘s first issue came out in January 1930, which is about as astounding as the magazine’s original name (Astounding Stories of Super Science).

This issue is marked by a supermajority of stories about humans dealing with aliens who pose a threat. The way humans deal with the aliens, though, varies widely through these stories–in a couple, we see humans at their worst, but in a few more we see humans behaving in a way that gives us more hope for our eventual maturity.

“Three Bodies at Mitanni” by Seth Dickinson takes place in space, four hundred years after a ship is launched from Earth on a mission to survey seedship colonies planted long ago. If necessary, part of that mission is to destroy the colonies if they might pose an existential threat to humanity, but such a case has not yet been discovered.

At the ship’s final stop, the planet Mitanni, the three crew members find a population that has exploded into billions in a relatively short period of time. The people have somehow been rewired to be totally, selflessly devoted to survival, at the cost of art, culture, and consciousness. The colony is an anomaly only theorized about, but never before seen–a Duong-Watts malignancy–whose potential spread through space could compete with and destroy all human life. The crew must weigh the near-certain threatening infiltration of the Mitanni into human space against the destruction of billions of lives and the possibility that the Mitanni may be the best chance of ultimate survival of any life form.

This story has very few characters, but each one represents a powerful point of view. Ethical problems are presented in all their complexity, with the full weight of repercussions even when a decision seems to be clear. The writing is gorgeous, tight and clear, the world-building impeccable. Smaller versions of these ethical dilemmas can be applied to present-day situations on our planet. This is a rich story, which I think would be valuable and enjoyable to a far wider audience than the usual fans of the genre.

“Ships in the Night” by Jay Werkheiser is a story within a story; Brad is an offworlder having a drink in a bar on the planetary outpost Nouvelle Terre. The other bar-goers are soon riveted by a story he tells of a near-escape from being roasted by an alien ship’s exhaust fumes.

This is a short, light-hearted piece with a punchline. It took me two reads to get that punchline, and as could be expected, when I did it was a much more satisfying read. The story is not terribly deep, but is fun and entertaining enough.

“Strategies for Optimizing Your Mobile Advertising” by Brenta Blevins is narrated by a starving artist of the future, whose poorly selling “office supply art” means he needs to take to the streets as an adwalker in order to make enough just to access his apartment at night. As an adwalker, he’s a futuristic version of those people who are paid to stand on sidewalks bobbing signs around to get drivers’ attention. His t-shirt is a mobile interface for companies contracting with him to catch the eye of pedestrians who, even with access to increasingly sophisticated technology for blocking ads, can’t avoid seeing a man jumping in front of them with a garishly flashing t-shirt. This story takes place on a day on which the protagonist’s t-shirt is malfunctioning, and he needs to figure out how to get it to work again.

This story takes a light-hearted angle on what I see as a somewhat depressing view of what society will look like given a predictable progression of both commercialism and technology. The tech evolves, but basic drives to survive versus urges to express ourselves authentically do not. Other things that don’t change are micromanaging mothers, and governmental inability to increase quality of life for the masses.

“The Audience” by Sean McMullen is another story that takes place in deep space and deals with a highly intelligent and possibly threatening other race. Here, five crew members aboard humanity’s only starship have arrived at the gas giant planet Abyss, on the first voyage beyond the solar system. As they begin to explore, they discover first that the ice comprising the ring system of Abyss is full of bacterial cells–indicating life, albeit presumably long-dead. Excited, they surmise that the ice is from long-ago impacts and that life may have continued to evolve in subsurface oceans on the planet’s moons. As discovery leads to contact with an alien intelligence whose attempts to understand humans leads to multiple deaths, the protagonist–a disaster recovery expert–is faced with having to try to avert a potential disaster that could affect all of humanity.

This story is kind of scary. All the work that went into choosing the perfect crew and making this amazing journey outside the solar system, and we’re confronted with the utter fragility of human life and all its sophisticated technology. I didn’t find the solution to the story very satisfying–the protagonist is trying to deceive the alien race in order to divert it from discovering Earth and potentially being a threat to humanity–but I didn’t understand why he didn’t just blow up his ship, if the motivation was solely disaster recovery. That said, there are fascinating elements to this story, and it’s thought-provoking enough that it has me thinking of all the ways I would try to deal with the situation in the protagonist’s position.

In “The Empathy Vaccine” by C.C. Finlay, Kyle Hastings is a hard-headed and selfish businessman who wants to get even harder-headed and more selfish by getting a procedure that will alter his gene structure by changing the nucleobase pairs on his oxytocin receptors to take away his ability to experience empathy. This “empathy vaccine” comes at a very high financial cost, and Kyle intends to have his cake and eat it too by shooting the doctor after the procedure is over. The exchange between the two before the procedure takes place is laced with tension; we witness Kyle’s motivations and the doctor’s reluctance. The doctor appears to be putty in Kyle’s hands–except, of course, there’s a twist.

This story is about a couple of despicable characters and their game of wits. The science is entirely plausible, although I couldn’t quite buy the plot. No one who deals with such vast sums of money would let someone come into his office and perform a procedure on him without checking him for weapons. And I don’t think a hard-headed, suspicious businessman like Kyle who already lacks considerable empathy would be so stupid as to allow the doctor to inject him with something without checking to see what it is first. Interesting idea with a lot of fascinating potential story applications, but the execution did not work for me.

“The Kroc War” by Ted Reynolds and William F. Wu tells the story of a war between humans and the Krocerian aliens. It’s told through multiple voices, switching from the viewpoints of various people involved in the war: a private, to a sergeant, an ambassador, a doctor, a senator, a Krocerian, among others. Through each of these limited viewpoints, the whole story emerges: humanity is doing the same empire-building with the same justifications as has happened throughout history with each dominant nation. This time, it’s in the realm of space. We demonize another group, we justify the need to conquer, we kill and absorb, we move on.

“Earth-brat, you humans learn how to get along with each other, and maybe how to think a bit, and then in a few hundred years, maybe you’ll be ready to talk to a Krocerian,” one of the Krocs tells a human, who takes the message entirely the wrong way. According to this story, it’s unlikely that humans will ever learn how to properly get along with each other or think.

Reading this story felt a lot like watching a movie. I enjoyed how each point of view was humanized, and I felt that the entertainment value of the story was enough to make the depressing message palatable.

“The Odds” by Ron Collins is a very short story of a person ruminating on the odds that brought him to the very day he’s living now. We are shown a picture about how humanity encountered another species, pretended to get along, and made the narrator the ambassador. Now the ambassador is getting ready for the moment he has to witness the ultimate betrayal, to which he is passively, but fully a party.

As in “The Kroc War,” “The Odds” paints humanity as short-sighted, bloodthirsty, empire-hungry liars. Amongst the liars, however, there are consciences. This story paints the picture of a conscience–of the horrible feeling when one knows one is doing something wrong but feels so utterly cornered that all one can do is smile and continue on one’s path. I found the story effective and emotionally sobering.

“The Wormhole War” by Richard A. Lovett is an alien encounter story with harder science than I’m used to, so I’m not sure I can do justice to a description. Zeke Schlachter is in charge of watching a wormhole, which has been created at great expense in an effort to explore the possibilities of space travel through the wormhole. Specifically, scientists have the idea to explore the nearest Earth-like planet within a hundred light years: Gaia 205c. However, the wormhole explodes and disappears without explanation. Zeke and others theorize, after creating more wormholes and watching them disappear, that there is an intelligent species–probably on Gaia 205c–which is causing the wormholes to disappear by launching their own. Decades follow in a “wormhole war” between the two; we see the slow erosion of Zeke’s personal life as he devotes everything to this war. He and his colleagues spend a lot of money and try a bunch of different ways to send and create wormholes in order to try winning, but the aliens are much better at it and their impending approach is obvious.

I didn’t understand the wormhole science at all, so all that was above my head and somewhat frustrating, as it seems crucial to getting the plot. Other than that, all I can say is that I found the story somewhat depressing, watching Zeke give up everything in this somewhat narrow-minded crusade which I think should have ended decades before with the same solution they tried at the end of the story. This is probably a story hard science fiction fans would enjoy; it was too much for me.

“Very Long Conversations” by Gwendolyn Clare is a breath of fresh air after all those other stories about humans in space and humans in depressing future times. There are alien species in this story as well, but they’re all friendly. Here, the protagonist Becca works in the field of interstellar fieldwork, and she’s exploring a foreign savanna. She has a few humans as companions as well as a couple of Albedans–who are intensely alien, multi-legged beings who communicate with feelers instead of with words. Becca’s curiosity about other species is a weakness that previously caused her to adopt an Albedan baby who now travels with her. But when she discovers a mysterious stick figure formed in the grasses that apparently is meant to symbolize herself, her weakness becomes a strength as she begins to explore yet another possible way of interspecies communication beyond what she’s experienced before.

This is a mellow story which presents itself in my brain like a scenic alien-world photo montage. It’s less about plot than about relationships, ways to connect, compassion, empathy. I found the characters sweet and likable, offering an encouraging view of a possible future and way of being to which we might aspire.