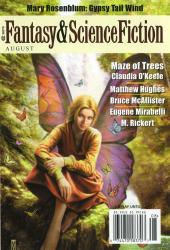

“Maze of Trees” by Claudia O’Keefe

“Gypsy Tail Wind” by Mary Rosenblum

“Refried Clichés: A Five Course Meal” by Mike Shultz

“A Very Little Madness Goes a Long Way” by M. Rickert

“Spell” by Bruce McAllister

“Pure Vision” by Robert Reed

“The Woman in Schrödinger’s Wave Equations” by Eugene Mirabelli

“Thwarting Jabbi Gloond” is as good of a science fiction mystery as I’ve read in a while. If it’s any indicator of the talent of Mr. Hughes, I look forward to seeing a lot of his work in the future, and I’ll have to go hunting for copies of his previous four Henghis Hapthorn stories, the most recent being “The Gist Hunter” in the June 2005 issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

An ex-Hollywood writer becomes the goddess of a small tract of pristine West Virginian wilderness in this issue’s second novelette, “Maze of Trees” by Claudia O’Keefe. There, of course, are catches: she can never leave that small tract of wilderness, and she has to use her powers to keep her wilderness pristine. As you can imagine, this is a rough assignment for a girl from perhaps the least pristine place in all of existence, until she finds someone just as out of place as she is. But, can the relationship between the wilderness goddess and the ex-systems analyst really work out?

“Maze of Trees” is a wonderfully evocative tale of romance, sacrifice, and ennui. Ennui can be a tricky thing—it’s a razor thin line between ennui and whiny—but I feel the author was able to stay firmly on the ennui side. Her prose was able to place me deep within the West Virginian hills while I sipped my iced mocha from the air-conditioned comfort of my local chain bakery/coffee shop while I was surrounded by several teams from a teenage girl’s softball tournament, which is no mean feat. I would give this story an unreserved thumbs up, except for one fairly major plot hole that either nullifies the emotional impact of the ending or requires an explanation as to why what happens only works in that particular circumstance. That said, I still highly recommend “Maze of Trees.”

A young woman from a repressive Islamic space station and her bi-personalitied business partner smuggle water to reclusive telepathic space gypsies in Mary Rosenblum’s “Gypsy Tail Wind.” For all those people out there who read that and thought, “Wow, telepathic space gypsies, I gotta get that story,” I say, “Right on!” For those of you who aren’t sold yet, rest assured there is more to the story than telepathic space gypsies. OK, there isn’t much more to the story than telepathic space gypsies, but when the idea of telepathic space gypsies is explored as thoughtfully as it is in “Gypsy Tail Wind,” which is much more thoughtfully than my glib use of the term “telepathic space gypsies” would suggest, you don’t need much more than that. It’s a fun piece of old school science fiction and serves as a good counterpoint to the more contemporary feel of “The Woman in Schrödinger’s Equations” later in this issue.

There is a serious danger in reviewing Mike Shultz’s “Refried Clichés: A Five Course Meal” of having the review be longer than the story. The title tells you everything you need to know: five speculative fiction clichés—a wish-granting genie, a time-traveling Adam and Eve, an eclipse-predicting human sacrifice, a hacking-slashing fantasy warrior, a gun-blazing female secret agent, and an evil-tempting succubus (OK, I was stretching to get the hyphenations there at the end)—each in its own story, told with twist. No, twist isn’t the right word. There is no twist: Mike Shultz just gives us these five clichés the way that we’ve really always wanted to see them, and it’s, oh, so satisfying. Almost more importantly, he knows when to stop. Each story is as long as it needs to be and no longer. And so, to “Refried Clichés” I give the heartiest of recommendations.

Angels, crows, madness, and depression: it’s been a while since I dove into the black half of my wardrobe and put on my black-stompy boots, but what’s left of my inner goth enjoyed M. Rickert’s “A Very Little Madness Goes a Long Way.” The story itself works well enough. After losing her daughter, a mother becomes convinced that it is the work of the crows. Her friends and relatives fear she’s going mad. But the story shines where it counts: style. If you’ve never had the urge to don a long coat and perch on the ledge of a building, and you’ve never worn so much as a black bit of string, then this story’s probably not for you. If, however, you’ve not quite yet thrown out your last bottle of black nail polish, then I’d suggest giving this one a read.

There is something evil in the world, and the little boy it wants to kill just lost his only protector—his grandmother. In all honesty, “Spell” by Bruce McAllister is not one of my favorite stories in this issue. The theme—that love isn’t always the sweetness-and-light it’s portrayed to be—and plot worked well. However, there is an awkwardness about the narrative style that, while it did a good job of making me feel the youth and vulnerability of the boy, kept me from full immersion in the story. It’s still a nice story, and worth reading if you have a copy of this issue.

And, now, I must get something off my chest: Spectacular spectacles. Ah, that’s better. Sorry, I was just about to use that phrase with far too much sincerity in this review, and, while I’ve realized how bad an idea that was, I still needed to get it out of my system. Thank you for bearing with me.

Yes, indeed, the next story, “Pure Vision” by Robert Reed, involves glasses with unusual abilities. It’s the ability to see men’s souls, to be exact, which, while not quite as sought after as the fabled Glasses of Cloth Transparency, is a pretty impressive trick. For all their spectacularity, it’s not the glasses that make this story; it’s the amoral semi-jerk of a narrator. This is a not man who is out to make a better world, and, to be honest, I like that about him. There is an escapist pleasure and, in this increasingly censorious age, subversive thrill in his mild misanthropy that makes this story a fun read.

The final story in this issue is “The Woman in Schrödinger’s Wave Equations” by Eugene Mirabelli. In this story, a woman reads a book on Schrödinger in order to chat up a physics student who is already seeing “a knockout.” This, unless things have changed since my days as a physics student, firmly establishes its street cred as a fantasy story. Joking aside, even the editor in his introduction to the story makes the comment that this story isn’t easy to stick the science fiction or fantasy label on. To be honest, that doesn’t bother me. I’ve had a hard time figuring out the dividing line between mainstream and speculative fiction since my local Barnes & Nobles put Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle in the Literature section and Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle in the Science Fiction/Fantasy section. All I care about is whether something is a good story.

So, is “The Woman in Schrödinger’s Wave Equations” a good story? Well, I like the somewhat distant voice of the piece, and the idea of a physics student having multiple dating options has definite appeal. It didn’t come out and grab me, though. It was a nice story, polite, but not something, I think, that will stick in my memory. But, I could be very wrong. It has a certain slippery je ne sais quoi about it that makes me understand why the editor included it and makes it hard to peg how I’ll feel about it in a year or two.