Tangent Online Presents:

An Interview with Wilson “Bob” Tucker

(November 23, 1914 – October 6, 2006)

Interviewers:

Dave Truesdale & Paul McGuire III

Location:

ICON I, (near) Iowa City, IA

Halloween Weekend 1975

Con Hotel Lobby

Interview originally appeared in Tangent No. 4, February 1976, and is reprinted here for the first time.

Introduction

There is so much to say about Wilson (Bob) Tucker I hardly know where to begin. The following interview took place at my third convention when I was still a wet behind the ears newbie fan, full of enthusiasm and the unbridled joy at having discovered fandom, and now conventions. Along with this interview, I also interviewed Roger Zelazny and George R. R. Martin at ICON I, which was held in a motel outside of Iowa City, IA. The Zelazny interview has yet to be transferred from its original print publication in the original Tangent, but earlier in 2014 I posted the George R. R. Martin interview here.

Wilson Tucker thought of SF fandom as his second family and treated it as such. He was active in fandom from the 1940s on, publishing fanzines (noted for their insight, criticism, and humor, especially Le Zombie), attending cons as a fan, toastmaster, and Guest of Honor, and extending his larger family by introducing thousands upon countless thousands of fans to the joy of SF fandom, most notably through one of the fannish traditions he began, that of Smooothing at convention party suites.

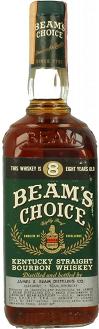

To Smoooth with Bob Tucker was a rite of passage for new fans, those attending their first convention. First time congoers are known as con virgins, you see, and Tucker’s rite of gathering con virgins in one of the empty consuites—as well as any other fans wishing to view or participate in the ceremony—and having them fill the room to standing room only capacity in many instances, was a joyful transition into fandom. The ceremony always involved a fifth of Beam’s Choice, that wonderful 8-year old “Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey” Bob was so fond of. The festivities began with Bob taking a swig and raising an arm high over his head. The bottle was passed to the next person, a swig and a raised arm would follow, and so on around the crowded room. When everyone had tasted of the ambrosia (with only wetted lips, or had played fair and imbibed an official sip or slug) and the bottle made its way back to Bob, swallowing would take place around the room and then Tucker—and everyone else—would sweep their upraised arms down and across their bodies, and Tucker would lead the group with a mellow exclamation of Smooooth. No con virgins remained. The bottle was then started on another pass around the room, repeating the initial process until the bottle was empty. Fans were now lubricated, spirits raised, and the con was off to a flush-faced and smiling start. And new friends were made. That was Bob Tucker, the fan.

Wilson Tucker, the author, made his mark as well with a number of critically well-received and popular novels, among them: The Long Loud Silence (1952); The Lincoln Hunters (1958); The Year of the Quiet Sun (1970); and Ice and Iron (1974).

The Long Loud Silence is a frightening post-apocalypse novel where a third of the U.S. has been devastated by nuclear blasts, and a biological plague infects virtually everyone east of the Mississippi. It chronicles in terse language, psychological insight, and bleak settings the travails of one man’s journey as he tries to break out of the military blockade of the Mississippi and make his way west. A slim book by today’s standards at just over 200 pages, it packs more of a wallop than less successful efforts three times as long. Damon Knight said of it: “…a phenomenally good book; in its own terms, it comes as near perfection as makes no difference.”

The Long Loud Silence is a frightening post-apocalypse novel where a third of the U.S. has been devastated by nuclear blasts, and a biological plague infects virtually everyone east of the Mississippi. It chronicles in terse language, psychological insight, and bleak settings the travails of one man’s journey as he tries to break out of the military blockade of the Mississippi and make his way west. A slim book by today’s standards at just over 200 pages, it packs more of a wallop than less successful efforts three times as long. Damon Knight said of it: “…a phenomenally good book; in its own terms, it comes as near perfection as makes no difference.”

The Year of the Quiet Sun was runner-up for the Locus Award, was a finalist for both the Hugo and Nebula, and was honored with a retrospective John W. Campbell Memorial Award in 1976 as Best Novel for its year.

Bob Tucker coined the term “space opera,” though its definition has undergone several metamorphoses over the years.

At one point in his career, Wilson Tucker began inserting names of friends as characters in his stories, something which has come to be known as Tuckerization. Over the decades many another author has adopted this practice for any number of reasons, and many of us have been “Tuckerized” in SF stories. Yet another tradition Wilson (Bob) Tucker began, and another lasting mark he has left on the field.

Tucker was awarded the First Fandom Hall of Fame Award in 1985, the E.E. Smith Memorial Award in 1986, and the Archon (St. Louis) Hall of Fame Award, Grand Master, in 1997. At a ceremony on the Queen Mary in 1996, Tucker was the second person honored by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America as Author Emeritus. In 2003 he was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame.

In 1955 he edited the Neo-Fan’s Guide (to the jungle known as) Science Fiction Fandom, an indispensable guide to fannish terms and fanspeak. It has gone through 8 editions and updating (the definition of many terms has drifted over the years), the most recent–and last–appearing in 1996 and published by the Kansas City Science Fiction & Fantasy Society (which, incidentally, will host the 2016 Worldcon in Kansas City). Here is a link to the original 1955 edition, including cover, commentary, and definitions.

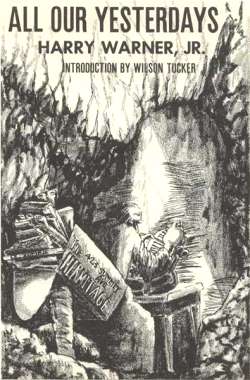

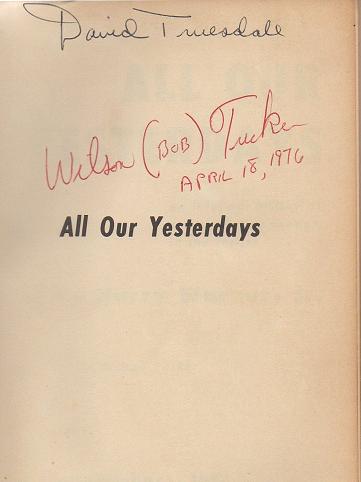

There is so much to be said about Wilson Tucker the man and author, and Bob Tucker the fan, that I hardly know where to stop. Many others, still alive and kicking, knew him much better than I ever did and can tell you much more about him than I ever could. So here is as good a place as any to end this brief introduction. If you Wiki “Wilson Tucker” you will get the essentials, but I urge you to click a few of the links there to get a more rounded picture of the man, the fan, and the author. He was such a major figure in fandom in so many ways over the years that he was asked to pen the introduction to Harry Warner, Jr’s. classic history of fandom in the 1940s, All Our Yesterdays. I urge you to seek this book out and read it thoroughly—then compare and contrast the good, the bad, and the ugly in fandom today. You’d be surprised at what you learn by reading history.

Herewith, my interview with Wilson “Bob” Tucker, sitting side by side with the tape recorder microphone between us, on a couch in the lobby of that ICON I motel on an early Sunday afternoon of Halloween weekend 1975.

TANGENT: We’d like you to tell us how you wrote Ice and Iron, and how you made a lot of money in the process.

TANGENT: We’d like you to tell us how you wrote Ice and Iron, and how you made a lot of money in the process.

WILSON TUCKER: (Laughing) All right. Judy Lynn del Rey is the science fiction editor of Ballantine Books. She read the hardcover book and she told me she didn’t like the ending. She told me—and this is not a quote, it’s a quasi-quote—do you know what I mean by a quasi-quote?

TANGENT: Yes.

TUCKER: She said it was a fine book, but it lacked an ending. She asked me if I would rewrite the ending. And I asked her if she’d pay, and she said yes. I did, and she did (chuckling). And the ending consists of rewriting the last chapter of the novel, the last chapter–13, of the hardcover, and adding two more chapters after that. I still like the ending of the hardcover myself, but uh….

TANGENT: Even though you liked it better, you were willing to change it?

TUCKER: She’s the professional editor. I don’t have the editorial eye she’s got. I liked the original ending because I prefer readers to figure things out for themselves. As a professional editor, she can’t afford to do that. She has to please her publishers; she has to sell books. Her editorial eye realized—in Western movies they have what they call “the walk down” or the gun battle—there must be a bang-bang or something to wrap up the story, so I gave her a bang-bang ending.

TANGENT: Did you have to really sacrifice anything in order to do that?

TUCKER: No. It was worth it. All I had to do was rewrite the thirteenth chapter, and I didn’t lose anything, I kept what I wanted, the background. No, it was worth it; it didn’t bother me. Things turned out very nice indeed.

TANGENT: I was particularly enamored with the hero. Toward the end he drove me crazy. I felt myself identifying with him in many ways, but if I had to work with him he’d probably get obnoxious.

TUCKER: The book started, in my mind, the book started out as a joke. By that I mean, I sat down and deliberately started a lighthearted, non-serious book, let’s everybody have fun. But it didn’t turn out that way. Books will take different courses, quite often. So I envisioned the hero to be a loose-jointed, loose-molded, in the sense that he wasn’t too terribly bright. But he was competent in his field; he could put things together. It was a comedy thing. Not a ha-ha comedy thing, just a lighthearted romp.

And it was even nominated for a Hugo. It didn’t get anywhere, but the whole thing surprised the hell out of me. You deliberately sit down to write a tongue-in-cheek book and somebody takes it seriously and nominates it for the Hugo! (Laughing)

TANGENT: Wasn’t The Year of the Quiet Sun nominated also?

TANGENT: Wasn’t The Year of the Quiet Sun nominated also?

TUCKER: Well, it came out in 1970, so it was nominated in 1971. The year that Ringworld won was the year.

You know how the Hugo balloting goes: anybody who joins the convention pays their dollar or whatever, and they get a ballot. Anybody can vote who joins the convention. And then the three or four or five hundred people do their voting and then the committee, usually the convention committee, narrows it down and takes the five books that have received the most votes. The five are put out on a final ballot. The winner is selected from the five.

So The Year of the Quiet Sun wound up in the top five. But in the actual voting it came in fourth or fifth.

TANGENT: What book of yours has satisfied you the most over the years?

TUCKER: The Lincoln Hunters.There were three copies of that one in the hucksters room on Saturday but they’re long gone now. I bought one myself, because I wanted a second copy.

The Lincoln Hunters is a historical novel about Lincoln in his day, in Bloomington, Illinois, in 1858, where he made a very famous political speech. The only science fiction angle to it was in the beginning four men in a time machine go back to 1858. If you’ll accept the fact and can discount the fact that there is a time machine and four time travellers, the book is a pure historical novel. And, I guess I liked it for that reason.

It was well researched. I lived in Bloomington at the time, and I found the place where the building used to be. It’s torn down now, it’s a parking lot. Anyway, I found where the building used to be, and the hall was on the second floor, and I succeeded in finding—not photographs of it—but some kind of a sketch like Harpers Weekly used to take of the war, and then I dug through the Bloomington library and succeeded in finding a book written by Lincoln’s law partner after Lincoln’s death. This man gave a very good description of Lincoln, even described his voice. And it wasn’t what you hear and see of Lincoln in the movies. He’s described as having a high, nasal, Kentucky twang.

It was well researched. I lived in Bloomington at the time, and I found the place where the building used to be. It’s torn down now, it’s a parking lot. Anyway, I found where the building used to be, and the hall was on the second floor, and I succeeded in finding—not photographs of it—but some kind of a sketch like Harpers Weekly used to take of the war, and then I dug through the Bloomington library and succeeded in finding a book written by Lincoln’s law partner after Lincoln’s death. This man gave a very good description of Lincoln, even described his voice. And it wasn’t what you hear and see of Lincoln in the movies. He’s described as having a high, nasal, Kentucky twang.

I used the time travellers solely to get my men back to Lincoln’s time. They were the springboard just to get the story moving. In the future, a museum curator stumbled across the fact that his researchers had a man named Lincoln that had given this historical speech, and no copy of it existed. And this is true; the speech is lost. It’s called “Lincoln’s Lost Speech.” So this curator decided…okay…I’ll be the only one in the world to have a copy of Lincoln’s lost speech. He declares a Time Research Company to go back and get him a copy of the speech. So he sends back the four men. He only needs one or two, but for story purposes I needed four. And the Time Research Company owns the only time machine around, and it’s a legal monopoly because they’re paying off the government.

So these four guys go back to Lincoln’s day armed with recorders, and from that point on it’s a pure historical novel.

TANGENT: How much of a businessman do you have to be, along with being a writer?

TUCKER: Every writer should be a businessman, but I don’t bother because I have an agent. A woman named Martha Winston is my agent. She works for a company named Curtis, Brown, Ltd. Curtis, Brown is an American and British concern. When I finish up a manuscript I simply deliver three copies to her and she takes it from there.

TANGENT: Why three copies?

TUCKER: The publishers want that one. The first two copies—for example, Doubleday—when you sign a contract with them, the contract calls for two copies. The editor wants one and then the art department wants one. If it’s bought, the art department goes to work immediately on it, while elsewhere it’s being proofread, copyread and so on. The third copy, meanwhile, is sent to London for an additional sale, and if the London publisher is quick enough—if his schedule permits—he can get his edition out as quickly as the New York edition. A lot of writers and agents…either they don’t know the score or they’re just not thinking of it…they’ll wait till the original hardcover comes out and then they’ll send it to a London publisher.

The way my agent does it is great. And each place, New York and London, copyrights it in their own country, so there’s no problem there. And she renews and takes care of all my copyrights for me, too, so I don’t have to worry about any of that.

And then when your agent sells a book to an editor, that’s when the real haggling begins. The agent tries to keep the price up and the editor tries to keep a lid on things, and that’s one of the things I’m glad I don’t have to do. I don’t work well in a crisis.

TANGENT: Are you afraid you’d give in on the price too easily?

TUCKER: (Chuckling) That’s right. I’d give in too easily and sign for a lower price.

The first book I ever wrote, back in 1946, I had to sell myself because a good agent will not take you until you’ve proven you can sell. She wouldn’t accept a book from a total stranger. Suppose she took six months on it and it didn’t sell; she’s lost six months worth of time and money when she could have been making money on other books. So, not being a good businessman and not knowing what to do, I sold that first book for $250. It was called The Chinese Doll. It was a mystery story.

The first book I ever wrote, back in 1946, I had to sell myself because a good agent will not take you until you’ve proven you can sell. She wouldn’t accept a book from a total stranger. Suppose she took six months on it and it didn’t sell; she’s lost six months worth of time and money when she could have been making money on other books. So, not being a good businessman and not knowing what to do, I sold that first book for $250. It was called The Chinese Doll. It was a mystery story.

I write both mystery and science fiction books, and adventure stories.

TANGENT: Do you like science fiction the best?

TUCKER: By far. I like it the best. But mysteries sell far better.

TANGENT: What are your favorite themes you like to work with in science fiction?

TUCKER: I like to just have fun with what I’m doing at the time. Time travel is my favorite; I’ve done it so many times. I think it’s fun to play around with time machines. Not like…I sometimes fall into the trap of the old hackneyed type of story, you know, someone goes into the past to kill his grandfather. I avoid that. But something like in The Lincoln Hunters I like. Where someone is trapped in the past and must use what they’ve learned just to stay alive.

TANGENT: Are you working on anything new right now? What’s in the works?

TUCKER: I’m doing a book right now that doesn’t even have a title yet. It’s called The Gilgamesh book. The story opens—I’m doing it the same way Ice and Iron was structured—in the opening chapter the hero and heroine are professional researchers. One of them is a ghost writer down in Florida. He’s got a huge library and is the type of guy who writes novels for busy doctors and scientists who haven’t got the time to do it. But he’s a smart cookie and he knows his fields, his subjects thoroughly. And the girl in the story is a photo librarian for Life magazine. There are five million negatives in their files and she has them all at her fingertips.

The two of them stumble across what is, to them, an unexplainable situation. They find this man’s picture in several places that just doesn’t make sense. For example, they find his picture in the Life Picture Book of World War I, and then later on they find it in World War II, and in another book they find his picture as a soldier in the Korean War. So this sets them off, and she starts going through Life’s picture file. She finds the guy in the Civil War, and then she turns up his face in an art book that was printed in Paris in 1790. And it’s the same man.

So they begin the search for this man that appears to be about 200 years old. And this is all in alternate chapters. One will be in present day as they uncover picture after picture, and one will be as they track him down, and so on. By the time they get to the end of the book they find that the guy is not 200 years old, he’s more like 10,000 years old. But as they work their way back, he’s working his way up to the present, and in the last chapter they meet. And what I’m going to do—I call him Gilgamesh because in 3,000 B.C. he was known as Gilgamesh, he was known as kind of a superman. He was probably in literature the first Tarzan or Superman—and what I’m going to do is go back to the Biblical flood, which was probably around 8,000 B.C., and have a man found in a reed boat just paddling around picking up chickens and dogs, and by the time he gets to shore he’ll have three or four people and six or seven farm animals, and from that, thousands of years later, will grow the story of Noah.

And then the third chapter will switch back to my researchers trying to track him down.

I haven’t decided really what I’m going to do next…

TANGENT: How much is written so far?

TUCKER: The first two chapters, and I’ll be starting now on the flood chapter. I’m still trying to figure out all the places I want to place this Gilgamesh character. I have a few for certain, like maybe Solomon’s temple, and the terrific earthquake that wrecked Lisbon in 1519, but I haven’t figured all the historical places I want him yet.

And I haven’t figured out what to do with him when they catch him. After all, what do you do with an immortal man? You can’t kill him, you can’t put him in jail, he’s committed no crime… I don’t know yet, but they might just turn him loose again. And anyway, who is going to believe these researchers when they say they have man that’s 10,000 years old?

TANGENT: I suppose you write full-time to support yourself, but do you have any other job or jobs?

TUCKER: I do write full-time now, but I used to have another job. You know, in the theatre they used to have electricians. I worked at that, and stagehand and projectionist. You’ve seen the rock shows, haven’t you, with the big flashing lights and so forth?

TANGENT: Oh, yeah, sure.

TUCKER: Well, I didn’t do that, because I didn’t know the cues, but—I work at two universities, Champaign and Illinois State—when the rock shows come in I’m the electrician who hooks up all their equipment. That takes a couple of hours of good work. That’s my job; that’s what I do. This only happens two or three times a month. This is Sunday; about a week, no, ten days ago I worked at the Jethro Tull show. And last week I was scheduled to work the Beach Boys but I couldn’t, I came here instead.

So, I write full-time and in my spare time I moonlight when a show comes along. I used to be a full-time projectionist, but I had to give it up because of my eyes. I had cataracts removed from both my eyes, and when I came back from the hospital they had automated my job. Once they put that new equipment in they didn’t need us. Oh, as a profession it’s dyin’ now, you bet. And all over the country, too. In my town alone, nine men lost their jobs.

My wife works for the telephone company, and when they transfer her I just pick up my typewriter and move along (grinning). She wants to keep her job, she likes it, so when these transfers come along she just accepts it. And it doesn’t bother me because I can write anywhere. I just pick up my typewriter and follow.

TANGENT: Before we go we’d like to hear the whole, true, and complete Rosebud story. What is the Rosebud story?!!!

TUCKER: Weeell, the Rosebud story! Now, let me do a bit of background. This happened during World War II, and life was simpler than it is now and motels were not the fancy things like this. In Bloomington the motel was called Cabin Town. It consisted of about half a dozen cabins in a gentle semi-circle around the manager’s cabin. In between, on a little grassy space, were some picnic tables. Now, this particular Cabin Town—in those days Cabin Town had a reputation, there weren’t…they were used by tourists on the road, but they wer ealso used by sports bringing their girls out from town. You come to a hotel the desk clerk wouldn’t let you in, but all the motels and Cabin towns would accept you; all day and all night you could rent them for an hour at a time. This was the kind of Cabin Town it was.

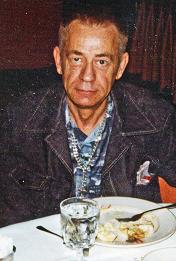

There was a fellow named Walt Liebscher (1918-1985 — photo at left by Dik Daniels, March 1982) who lived in Chicago and he’d come down to Bloomington and we’d have weekend cons together. I was going with a girl, and my girl would get a girl for Walt. The four of us would go out doubledating. And invariably, after the bars closed, and the bowling alleys closed, we’d wind up at Cabin Town. We couldn’t go to the girl’s house, she was living with her mother, and we couldn’t go to my house because I was living with my sister, so you see our problem. So we went out to Cabin Town and they had one double cabin there, and Walt and his girl would take one room and I and my girl would take the other. And we’d spend the night, the rest of the night, and along about sunrise get up and go home.

There was a fellow named Walt Liebscher (1918-1985 — photo at left by Dik Daniels, March 1982) who lived in Chicago and he’d come down to Bloomington and we’d have weekend cons together. I was going with a girl, and my girl would get a girl for Walt. The four of us would go out doubledating. And invariably, after the bars closed, and the bowling alleys closed, we’d wind up at Cabin Town. We couldn’t go to the girl’s house, she was living with her mother, and we couldn’t go to my house because I was living with my sister, so you see our problem. So we went out to Cabin Town and they had one double cabin there, and Walt and his girl would take one room and I and my girl would take the other. And we’d spend the night, the rest of the night, and along about sunrise get up and go home.

On this particular day it was a warm, sunny night, beautiful night, the stars out. And you recall, this was just after 1940 when Citizen Kane was released, and do you remember the rosebud in Citizen Kane? So, the word was on everybody’s lips, everybody knew what rosebud was; it was an “in” word at the time. Walt and I and our ladies went to Cabin Town this particular night and about four or five o’clock in the morning we got up, got dressed, and went outside on the picnic tables just batting the breeze for the last hour or so before we went home. And then we decided, well, let’s just have one more for the road before we go. So instead of going back into the cabins we laid our ladies down on the picnic tables.

Now, we weren’t preverts, we took separate tables. (Grinning pleasantly) And we had one last one for the road out there under the stars. As I say, it was a pretty warm night and very nice. Liebscher scared the daylights out of the rest of us. Just after he finished he rose up on his hands and threw back his head and howled at the sky, “ROSE-BUD!!!” Lights began going on in all the cabins around us, lights went on in the manager’s cabin, we jumped up, got in our clothes, ran for the car and got the hell out of there! So, (laughing) that’s how it happened.

Now, we weren’t preverts, we took separate tables. (Grinning pleasantly) And we had one last one for the road out there under the stars. As I say, it was a pretty warm night and very nice. Liebscher scared the daylights out of the rest of us. Just after he finished he rose up on his hands and threw back his head and howled at the sky, “ROSE-BUD!!!” Lights began going on in all the cabins around us, lights went on in the manager’s cabin, we jumped up, got in our clothes, ran for the car and got the hell out of there! So, (laughing) that’s how it happened.

Now, after he did that, I published the story in some fanzine or other and it got circulated in fanzines. Well, it became known in fandom as a synonym for a sexual climax of an encounter. Instead of saying, I did so-and-so last night, people would say, “Last night I had a fiiine rosebud!” Or you’d meet a guy at a con and you’d say “Rosebud!” and he’d say, “Yeah, yeah, yeeaahh!!” It took the place of another word. Are you familiar with Harry Warner’s history, All Our Yesterday’s? It’s a hardcover book about the history of fandom. And sure enough, “Rosebud” got into that book.

I’m now in the enviable happy position of having helped to create history that is now in our history books. And that is the Rosebud story.

ᴥ ᴥ ᴥ

{As fate would have it, I ran into Bob Tucker early the next year in Minneapolis for Minicon 11 in April of 1976. Lo and behold he was party hopping with a lady who turned out to be the unnamed lady in the famous Rosebud story. Her name is Mary Beth Colvin–pictured in a group photo with other SF fans from the 1940s in All Our Yesterdays. When I ran into Bob in the hallway of the party floor, he recognized my nametag and pointing to Mary Beth exclaimed “This is her, from the Rosebud story. She’s the one!” Hence the laughter from both of them in this shot, which I took seconds afterword. Quite a reunion. Story circle complete.}

![]()

Closing Thoughts

Decades of going to conventions, partying, drinking, and smooothing eventually took its toll on Bob Tucker, as well as the natural process of aging. A good decade before his passing he was advised by his doctor to cut out the drinking, and to slow all the rest of it down a bit. Which, very much for the most part he did. He still continued to deflower con virgins with many rounds of Beam’s Choice at conventions, though, but with a mere wetting of the lips as the bottle was passed around. No more legitimate drinking for Bob.

Before all of this, however, and years prior to his doctor’s orders to scale everything back, I made it a point to be standing next to Bob and help him finish the last two sips from a bottle of Beam’s Choice after a particularly rousing Smoooth session at some con or other. I saved that now empty bottle; it resides in an honored place on one of my bookshelves. Thanks for everything, Bob; the stories, the fun, and all you gave to SF in every way you could manage. Here’s one for you.

Wilson Tucker interview and photos copyright © 1976, 2014 Dave Truesdale and Tangent Online.

All rights reserved.