A Visual History of Science Fiction

(Published July 2014)

Edited

by

Jim Emerson

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

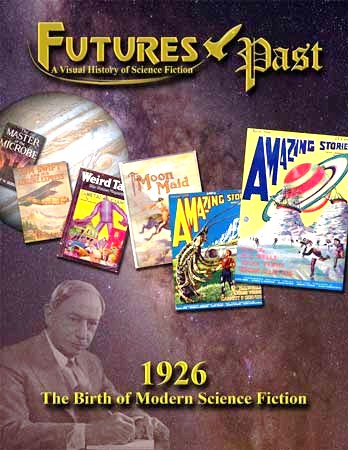

Futures Past is Jim Emerson’s history of science fiction from 1926 to 1975. The first volume – centered on 1926 – opens with an editorial opposite an image of the editorial with which Hugo Gernsback introduced the first issue of Amazing Stories in 1926. The old typeface and its archaic reference to SF as “scientifiction” serve as cogs in a time machine, delivering readers to an age in which the SF genre hadn’t yet been named. But it existed. Gernsback makes clear in referencing authors like Verne and Wells that he’s not proposing a novelty but promoting the best of what he knows can be done. Emerson’s first volume carries the time travel onward for more than fifty pages.

Photos pair with excerpts from John L. Coker III’s Tales of the Time Travellers yield colorful anecdotes. SF editor and literary agent Forrest Ackerman is depicted in a photo around the age he first spotted Amazing Stories at a newsstand, with a quote about his mother’s alarm at his growing magazine collection. Printer Conrad H. Ruppert is depicted with editor Julius Schwartz beside explanations of how each first encountered Amazing Stories and how it impacted their lives. A list of historic facts from 1926 provide perspective for the study of the origin of some of our most beloved science fiction: not only notable publications but archaeological discoveries, notables’ births, political upheavals, and social facts provide setting for the study of SF in 1926. On May 20 that year, Congress first authorized the Department of Commerce to issue aircraft pilots’ licenses. This, years after Verne described travel to the moon – and setting expectations of human flight as an everyday occurrence. Amazing Stories’ motto seemed a good fit: “Extravagant Fiction Today – Cold Fact Tomorrow.”

The outlook on SF from 1926 is as interesting to experience through then-current observers’ hopes, dreams, and accomplishments. Emerson doesn’t do all this work alone. Excerpts of other works exploring the history of science fiction describe the evolution of “scientific fiction” or “scientifiction” or whatever contemporaries were then calling it. The Gernsback Days by Mike Ashley and Robert A.W. Lowndes is excerpted through the presentation of its Chapter 9 on Gernsback’s different fiction-selling ventures. The second chapter of The Time Machines by Mike Ashley follows, describing Gernsback’s work to promote quality science fiction – eventually building a circulation exceeding 100,000. Interestingly, Gernsback’s supply of top-quality fiction (he felt obliged to rely on reprints for much of his material) ran against public demand for reading material: subscribers preferred he publish twice a month, a schedule Amazing Stories could never meet. The development of science fiction echoes tensions that remain today: may science fiction venture into fantasies that violate known physical laws, or must all such work strictly comport with whatever laws of the universe are known at the time of publication? Must SF educate on science, or is it enough that it present a gripping yarn? Modern readers may benefit from scholarly examination of influential stories about which they’ve never heard – but anyone with an interest in the field can enjoy learning where it came from, how, and who did it. A look at the difficulties that faced Greensback may put some current issues into perspective: the short story business has been tough to run as a business since before we called SF by that name. From the perspective of SF shorts as a business concern, page 25 may be most instructive. A story contest invitation from Amazing Stories shows that first-place entrants could earn as much as $250 for a story up to 10,000 words in 1926.

Jim Emerson’s own article “Weird Tales: The Unique Magazine” explains how a Poe fan trying to save a dying detective pulp periodical was founded to split overhead costs and raise revenue. Did you know Harry Houdini was a fan of Weird Tales, and that H.P. Lovecraft ghost-wrote “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” for him? If this kind of historical celebrity-spotting sounds like fun, this is a great read. It’s also a story about survival – for the publication. Born out of the financial peril of another magazine, Weird Tales struggled to remain in continuous publication and occasionally halted. But what a colorful story; the publication attracted writers much more varied than its three-color covers.

Alongside articles about Amazing Stories and Weird Tales stand listings of stories appearing in them, accompanied by miniatures of each issue’s covers. These maintain the feeling one is transported in time: the images of what presumably felt futuristic to the 1926 viewer vary widely. Some covers hold up well as SF even today, but some look like posters for cheap monster movies. But we can’t knock monster movies too hard: Pacific Rim and the new Godzilla prove these have an audience still. And the stories? They range from reprints of things that were 80 years old and hold up still, to works many readers won’t know at all.

In his article “Other Dimensions: Argosy All-Story Weekly,” Emerson describes The Argosy and its later companion publication The All-Story (with which it was later merged) as each fought for a profitable market segment. By 1903, The Argosy transformed into an all-fiction magazine printed on untrimmed pulp, pitched to male readers; it reached a monthly circulation of 500,000 copies. Competition swelled, and pulp fiction boomed. The All-Story included SF from its launch. Emerson traces these magazines’ role in broadening science fiction’s availability and describes their rise, merger, and fall. Frank A. Munsey, founder of The Argosy and The All-Story, died wealthy at 71 on December 22, 1925; 1926 closed their founders’ era, though not Argosy. The publication continued for decades, though it switched to slick paper, then from SF, and went through several decades of intermittent publication after 1978 until its revival in 2003 to offer “low-cost, quality pulp fiction in ebook format.” Argosy now seeks to deliver both classic pulp reprints and original modern SF.

Futures Past provides succinct reviews of some fifty SF books from 1926, which range all over in setting and topic. They illustrate that fiction has long intertwined with real life: when The City Without Jews author Hugo Bettauer was shot to death in Austria after writing about the eventual impact of expelling Jews from Austria, his murderer Otto Rothstock served an eighteen-month sentence before resuming a prominent position in the National Socialist party. By contrast, Edgar Rice Burroughs’ The Moon Maid offers a space romp culminating in a thwarted alien invasion of Earth. Sometimes we grow our monsters at home – and sometimes we import them. The cover art on the reviewed volumes conveys a deep sense of setting in yesteryear. But for a real sense of time travel, Emerson summarizes four SF films of 1926, of which two are presumed lost and have no known recordings. In The Radio Detective, for example, a Scout troop thwarts an evil syndicate bent on stealing their Scoutmaster’s invention for its own evil purposes. You may not want to watch these films, but you can’t stop reading about them any more than take your eye from a train wreck.

There are forty-nine more volumes following Emerson’s first – each year is covered from 1926 to 1975. The problem facing Greenback and ultimately Amazing Stories seems foreshadowed even in this first volume. His aspirations for the genre embraced not only entertainment, but instruction. Gernsback observed that “the best of these modern writers of scientifiction have the knack of imparting knowledge and even inspiration without once making us aware that we are being taught.” Amazing Stories’ masthead text illustrates Gernsback’s aspirations: “Extravagant Fiction Today – Cold Fact Tomorrow.” The tension between education and entertainment, and the fight to find a steady supply of high-quality work, seem too much to carry on nonstop, month after month.

From where we stand today, though, it’s interesting to see what could be accomplished. A month-by-month listing of 1926 short stories, several exemplars of covers, and a fun hatful of anecdotes about the effect these had on writers they drew to the genre – it’s a story itself. Entertaining and educational.

C. D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.

[Editors note: A free sample of this first issue of Futures Past can be downloaded by clicking on the cover. Highly recommended for anyone with an interest in the history of the science-fiction genre, with text and visuals rarely, if ever, found between the covers of a single publication. The exhaustive research alone is worth the price of admission.]