Tangent Online Special Review:

Tangent Online Special Review:

Special “Women Destroy Science Fiction” Issue

* * *

[Editor’s note: Learning of Lightspeed editor John Joseph Adams’ desire to publish this special issue, I decided it would be appropriate to publish a special review. Below you will find reviews, or commentary, of Guest Editor Christie Yant’s editorial, the fiction, non-fiction, and personal essays included in the June 2014 issue of Lightspeed. We have not reviewed the numerous pieces of flash fiction, the reprints, or the novel excerpt. At present, Tangent Online has a staff of 18, 8 females and 10 males–not counting myself. All were given the opportunity to participate; some did and some could not due to their schedules, various personal obligations–family or work–or other pressing review obligations.]

Christie Yant’s Guest Editorial:

“Women Destroy Science Fiction”

[Editor’s note: I asked the review staff for two females and two males to offer their thoughts on Ms. Yant’s Guest Editorial. The following staff members eagerly volunteered.]

Response and commentary by:

Martha Burns, Cyd Athens, Clancy Weeks, and Ryan Holmes

Martha Burns–

Christie Yant, guest editor for this issue, clarifies the sense in which women are presently or could or should destroy science fiction. She asks us to look at one often unexplored and unacknowledged perception that undergirds publishing and marketing decisions in the larger field of speculative fiction, which is that “science fiction” things–technology, biology, physics, astronomy–are for boys and “fantasy” things–fairies, mermaids, glittery vampires–are for girls. That understanding is silly, of course, but Yant points out that it affects reader expectations, literary valuations, author experiences and, most critically, the permission a writer needs to create whatever he or she wants. It needs to go. As it turns out, it’s very simple to destroy that understanding of what constitutes science fiction. Produce an anthology with work by female writers (take away the boy/girl split) who play with both science fiction and fantasy elements as traditionally understood (robots and mermaids) within the context of stories that explicitly refer to science and technology and those that don’t. In addition, the authors play with tropes regarding femininity and don’t worry that the decision makes one too much or not enough of a feminist. They do not have to worry that the project makes one shrill. Voila. And the stories work. They are well told, engaging, sometimes funny, occasionally moving. The nonfiction explores the myriad ways this perception plays out and are not to be missed. Now we can say that science fiction in this specific and unhelpful sense is destroyed.

Martha Burns has taught critical thinking, economic philosophy, feminist theory, yoga, and, in a poorly considered move, high school English. She reads, writes, reviews, and plays a lot of World of Warcraft.

Martha Burns has taught critical thinking, economic philosophy, feminist theory, yoga, and, in a poorly considered move, high school English. She reads, writes, reviews, and plays a lot of World of Warcraft.

*

Cyd Athens–

Christie Yant’s guest editorial, “Women Destroy Science Fiction,” begins with a 1991 quote by Tiptree Award co-founder, Pat Murphy, in which Murphy alludes to rumblings that women are destroying the genre by writing stuff that isn’t “real” science fiction. Yant then fast forwards to 2013 and “a certain subset of the field” that still doesn’t welcome women in the genre. She addresses responses to the undercurrent, including the June issue of Lightspeed and the 2014 all-women’s speculative anthology, Athena’s Daughters.

There are a couple of important points here that could be easily overlooked in the chaos of action and reaction. First, rather than a “majority,” Yant is discussing a “subset” though its size is never clarified. While any discrimination—to call it anything else would be disingenuous—is unacceptable, one who is convinced against his or her will is of the same opinion still. In other words, the best way to shut down disbelievers is to prove them wrong by doing the thing they insist you cannot, or should not, do. The second point is that Athena’s Daughters is but the latest entry on a list of all-women’s speculative anthologies that goes back forty years. Information about some of the others can be found at http://iansales.com/2014/04/17/women-only-science-fiction-anthologies/.

Yant goes on to briefly touch on the insidiousness of internalized oppression and how some women keep themselves from writing science fiction because they have subscribed to the subset belief that there is only one true way to write the stuff, and it must include rocket ships, robots, and extra-planetary adventures. Oh my. This editorial serves as both introduction and explanation for the June Lightspeed issue. It is also a celebration of what can happen when people believe in themselves enough to tell the subset of hostiles to shove it up Uranus.

Cyd Athens, a pronoun-fluid, black, gay woman, and associate editor of multiple speculative fiction humor anthologies, has been a speculative fiction aficionado for almost fifty years. His gateway drugs included The Arabian Nights which led him to harder stuff written by authors such as C. J. Cherryh, Mikhail Bulgakov, Katherine Kurtz, Samuel R. Delany, Tanith Lee, Jack Vance, and Ann Maxwell. From such modest beginnings, both his genre habit and his reading list have grown exponentially. Comments on Cyd’s reviews are welcome at www.cydathens.net.

Cyd Athens, a pronoun-fluid, black, gay woman, and associate editor of multiple speculative fiction humor anthologies, has been a speculative fiction aficionado for almost fifty years. His gateway drugs included The Arabian Nights which led him to harder stuff written by authors such as C. J. Cherryh, Mikhail Bulgakov, Katherine Kurtz, Samuel R. Delany, Tanith Lee, Jack Vance, and Ann Maxwell. From such modest beginnings, both his genre habit and his reading list have grown exponentially. Comments on Cyd’s reviews are welcome at www.cydathens.net.

*

Clancy Weeks–

Christie Yant has a point in her guest editorial in the June issue of Lightspeed. The problem is that I don’t think it was the one she intended to make. Back when I was a teacher and dealing with angry parents, a friend of mine used to say “perception is reality.” I argued reality is reality, and perception is irrelevant. In doing so, however, I inadvertently discounted the feelings of those involved. People will always believe what they want to believe. For instance, Ms. Yant wants us to believe that women authors are oppressed in the world of SF, but while there is certainly an aura of “boy’s club” to the genre, it has never been monolithic in nature. While I haven’t read any, I don’t dispute her claim that “There were multiple articles returning to the tired accusation that women (still) aren’t writing ‘real’ SF” over the past year.

The real point, then, becomes “what is SF, and who maintains the standards?” In 1947, the great John W. Campbell said,

“To be science fiction, not fantasy, an honest effort at prophetic extrapolation from the known must be made. Ghosts can enter science fiction—if they’re logically explained but not if they are simply the ghosts of fantasy. Prophetic extrapolation can derive from a number of different sources, and apply in a number of fields. Sociology, psychology, and parapsychology are, today, not true sciences: therefore instead of forecasting future results of applications of sociological science of today, we must forecast the development of a science of sociology.”

Theodore Sturgeon was a bit more succinct in 1953 when he said,

“A good story is good science fiction when it deals with human beings with a human problem which is resolved in terms of their humanity, cast in a narrative which could not occur without the science element.”

By 1987, Kim Stanley Robinson defined SF as “an historical literature… In every SF narrative, there is an explicit or implicit fictional history that connects the period depicted to our present moment, or to some moment in our past.”

Clearly, then, there has been an ongoing evolution in the definition and limitations of SF, and the unrelenting truth of the matter is that SF has changed over the decades. I won’t make a value judgment as to the worth of the changes, but it has changed. Did those changes occur because of the increasing number of stories from women authors? I don’t know, but I do know that Bradbury was writing stories of this nature long before the discussion came up. I, myself, have made the claim for a few years now that all fiction falls under the dual umbrellas of SF and Fantasy. Fiction, by its very definition, is a story about something that didn’t actually happen—and what is that but Fantasy? The concomitant point is that which is not Fantasy is, therefore, SF. With that definition in hand the umbrella is large indeed, and fully encompasses any form that women—or men—wish to explore.

I don’t buy into the notion that women are destroying Science Fiction, because it is just too big to kill. Ms. Yant makes the point that “Too many accomplished writers are convinced that they aren’t qualified to write science fiction because they ‘don’t have the science,’” but every writer who is not also a scientist—and some who are—feels this way. This is not a man vs. woman thing. It is a writer thing.

Is there a boy’s club atmosphere to the genre? Of course there is. The largest consumer bloc is young males, after all. It doesn’t have to be that way, and it is changing. More importantly, no one has to feel bad because our perception of reality is skewed. We just have to roll up our sleeves, write great stories, and press that submit button as often as possible.

Dr. Clancy Weeks taught Texas bands for over twenty years after graduating from Lamar University with a degree in music theory and composition. He has composed and arranged for the wind band medium for nearly thirty years (beginning in high school), and has had over two-dozen band and orchestra works published by R.B.C. Music and Avalon Press. His works have been performed by ensembles all over the country—including the Dallas Wind Symphony, the Houston Symphonic Band, and the Rutgers University Wind Ensemble. Clancy is a member of Texas Bandmasters Association, Texas Music Educators Association, American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), the College Music Society, Phi Mu Alpha, and Kappa Kappa Psi.

Dr. Clancy Weeks taught Texas bands for over twenty years after graduating from Lamar University with a degree in music theory and composition. He has composed and arranged for the wind band medium for nearly thirty years (beginning in high school), and has had over two-dozen band and orchestra works published by R.B.C. Music and Avalon Press. His works have been performed by ensembles all over the country—including the Dallas Wind Symphony, the Houston Symphonic Band, and the Rutgers University Wind Ensemble. Clancy is a member of Texas Bandmasters Association, Texas Music Educators Association, American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), the College Music Society, Phi Mu Alpha, and Kappa Kappa Psi.

Having been an avid reader of SF/F for nearly fifty years, he figured “What the hell, I can do that,” and has set out to prove that, well… maybe not so much. He currently resides in Texas with his wife and son, where he conducts a community band… but don’t hold that against him.

*

Ryan Holmes–

After reading Christie Yant’s editorial for Lightspeed’s June special issue, “Women Destroy Science Fiction,” we might muse for some time about what to glean from it. My musing turned to daydreaming of time travel, as is often the case. My interpretation of Yant’s article took a speculative form, one I decided to share.

Time travel is a tantalizing and popular trope of science fiction. Imagine a tale about a bright, female scientist—a science-fiction fan—who invents a time machine and travels back in time. Her goal is not to alter history. She merely wishes to enlighten the ladies of the past about the amazing contributions women have achieved in both science and science fiction. She can’t bring much, so she brings the latest, the freshest examples of female authors in science-fiction. She brings the June 2014 issue of Lightspeed. She proudly pushes it into the feminine hands of great scientists and science fiction authors, women like: Margaret Cavendish (17th century philosopher and first woman to author a utopian novel, The Blazing World), Sarah Scott (18th century author of A Description of Millennium Hall), Mary Shelley (19th century author of arguably the first science fiction novel Frankenstein).

Quite frankly the list goes on and is extensive. These amazing women take the periodical and rifle through imaginative and inspiring stories of women contributing to the future. Then they turn to the editorial by Christie Yant and read her opinions of how women have not succeeded in a male-dominated field of science and science-fiction. Instead of these historic women reading their great efforts touted as the farsighted achievements that they are, they read ‘that women (still) aren’t writing “real” SF’ and find only the latest and subpar women’s science fiction cited. They read that somehow science and by extension science fiction is easy, that instead of the daunting challenge of grasping complex principles, anyone can do science and anyone can write science fiction.

Now they look at our female time traveler. Do they look at her with pride and wonder for the future accomplishments of women and science? Do they look perplexed, confused, perhaps even insulted that they hold this issue in their hands with its many examples of women succeeding in furthering their footsteps but which is marred by a negative editorial choosing only to dwell on vague references to a few misguided articles and choosing not to honor the hard work preceding the issue(s) they pioneered? Does our female time traveler succeed in enlightening these pillars of feminism? Do they chastise her for thinking men could keep the world from recognizing greatness regardless of gender? After all, they succeeded when the world was truly sexist—not in a world with only a barely perceived veil of gender injustice—and they didn’t use it as a crutch. They led by fine example, nay extraordinary example, and now they don’t even get a mention.

Let’s not fan fires of negativity. Let’s not belittle science and by extension science fiction by suggesting it’s easy to do well. Let’s be positive and honest. Let’s give tribute to the hard work of those that came before us and celebrate the efforts of the brightest stars shining today. Encourage new science fiction authors but don’t lull them into a false sense of security that somehow science fiction can be easy, that it can be anything. Men and women alike who believe that falsehood WILL destroy science fiction, arguably the hardest genre in literature to write – yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

To summarize the effect of this editorial, imagine a crowded street party celebrating the great contributions of men and women in science fiction. Yant stands alone on the sidewalk and tries to outshout the jovial crowd by claiming foul at those who know better. Unfortunately, those who don’t, hear her rant and listen.

Ryan Holmes is a former United States Marine, a NASA aerospace engineer, and a father of three beautiful girls. In life’s scant margins, he writes and reviews science fiction and fantasy, striving to become an accomplished author, because the hardest paths change us the most and the challenges ahead keep us living. His blog can be found at: http://griffinsquill.blogspot.

Ryan Holmes is a former United States Marine, a NASA aerospace engineer, and a father of three beautiful girls. In life’s scant margins, he writes and reviews science fiction and fantasy, striving to become an accomplished author, because the hardest paths change us the most and the challenges ahead keep us living. His blog can be found at: http://griffinsquill.blogspot.

Short Fiction Reviews

[Editor’s note: Since the fiction in this issue was penned entirely by women, I asked that only women reviewers handle the reviews. Originally there were three reviewers, but due to a misunderstanding and a scheduling conflict there are now but two. I wish to thank Martha Burns for stepping into the breach at the last moment and doing double duty.]

Lightspeed #49, June 2014

Lightspeed #49, June 2014

Reviewed by Martha Burns

“Each to Each” by Seanan McGuire is a must read. It includes lush writing that rewards re-reading and complex themes that deserve attention. The piece serves as a fitting introduction to an anthology that explores, through the lens of science fiction, the dynamics of gender. The U.S. Army has modified female soldiers to explore and claim the last frontier – the sea. Some of these mermaids are shark-like, some jelly-like, and so on, but the military has made sure they all have big boobs and womanly curves as a way to win support for the program. This rings true as an example of how economics (big boobs and curves probably would win support for the program, frankly) intersects with sexism. When one of the soldiers is attacked, one of the more human-like mods goes to investigate and uncovers the possibility of the mermaids living together one day in a new Atlantis where they will, to use T.S. Eliot’s line from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” sing each to each. In the poem, this is meant to illustrate men being shut out of women’s world. In this story, the reference is used to show the joy of being in that women’s world, yet this is no easy utopia. Simone De Beauvoir noted that one is not born, but made a woman and in the story women are remade in a way that robs them of humanity and – McGuire is very clear on this point – deforms them. Yet, rather than reject the deformity, they embrace it and use it to escape to a better world. Some might argue that what should really happen is the mermaids should rise up against the military, but that’s too easy and good science fiction never takes the easy way out. This is good science fiction.

Maureen, a sculptor, has won a fellowship for her work and to pass the time on a trip to the planet Hippocrene, she works on a new piece using, not a live model, but a dead model, specifically, a decomposing dead man. We’re happy to wait for a solution to this mystery while “A Word Shaped Like Bones” by Kris Millering delivers quotable lines such as: “The dead man decays at her in what she feels is a possibly reproachful fashion.” The reader should, however, beware. Things get extraordinarily gross as the dead man only gets deader, the ship’s gravity fails, and the food recycler needs something to recycle for Maureen. Do not even consider lunch while reading the story. For all of the story’s considerable merits, the resolution to the mystery is, sadly, more prosaic than the set-up and includes the message that women who prioritize art over romance will ultimately be punished.

Spencer is a cyborg spy and that used to be fun for him, though he certainly was never James Bond with circuitry. He’s a skinny man who has to drink Ensure to provide the calories his program needs, he has to put up with strip searches at the airport so the security agents can check out his cool hardware, and he’s tormented by his inability to forget anything, especially after his last mission. In “Cuts Both Ways,” Heather Clitheroe uses a time-honored science fiction trope–the uncomfortable interaction of technology with humanity–in a fresh way. The point isn’t that technology diminishes Spencer’s humanity, but that it makes it impossible for him to distance himself from it. The distance, Clitheroe suggests, is necessary to happiness. Rich sensory and emotional descriptions increase the experience of the story.

Following an environmental disaster, scientists create sentient parasites they implant, first, in the bodies of enemies of the state and, then, in people raised for that purpose. The parasites in their human hosts create a perfect civilization except, of course, for breeding human beings that then die at transfer. A fully human worker in a transfer facility (who cannot have a Master implanted due to a genetic disorder) facilitates a transfer into a body of a fourteen-year-old boy she’s grown fond of. The boy, Enri, visits Sadie in dreams and lets her know about the nefarious goings on. Sadie then figures out a way to arrange a transfer that will be the Masters’ last. Crisply told, “Walking Awake” by N. K. Jemisin falters only in the explanation for why Sadie is both damaged goods and is able to receive the information from Enri’s spirit. She’s bipolar, a fashionable illness at present, much like Asperger’s. The story would in no way have been harmed by having a simpler and less prejudice-laden affliction to explain Sadie’s abilities such as, say, any frontal lobe seizure disorder. As the story’s theme itself demonstrates, it is a fine line between rescue and exploitation.

In “The Case of the Passionless Bees” by Rhonda Eikamp, Watson solves the murder case meant for Gearlock Holmes, which is the only way it was going to be solved since Holmes was the murderer. Holmes, troubled by his mechanical nature, commits this senseless act to let him feel something, anything, a bit of what it’s like to be human. When the murder of a stranger doesn’t yield that result, Holmes attempts to kill Watson, but still the clockwork Holmes remains nothing more than a cold, clever machine. The story’s twist is, on one way of looking at things, a gimmick that allows yet another Holmes-inspired tale. However, like all android stories, the story asks us to consider our understanding of humanity, specifically our attraction to the original, equally unfeeling flesh-and-blood detective. Isn’t our desperation to avoid emotion what the real Holmes represents to us, the glory of pure reason? It’s not a good life, the story suggests, to be such a reasoning machine, but it would take a robot to acknowledge that. This is an insightful addition to the Holmes cannon.

Gabriella Stalker‘s “In the Image of Man” is enjoyable precisely because it does things that spoil so many other stories. Nice trick that. Wendell lives in a mall and his life is dominated by spending all of the teen funds the state so happily loans him at usurious rates. He thinks in terms of chain stores ( the ones we all know and loathe) and feels put upon when he has to walk anywhere. Things change for him when Trent becomes his partner in an economics project and Wendell stuns himself with a desire to go to a church outside of town. Trent has no time for teen funds and his family lives at Walmart so they can, gasp, save for a single family house. Yes, Wendell finds redemption and yes he finds freedom from corporate capitalism. He also becomes free of racism and embraces the beauty of nature. This is not tired in Stalker’s hands because, first, it is so funny and, second, she joyously overdoes things. The messages are as big as an Olive Garden sign and that makes those messages seem less cloying and more like in-jokes stretched to their limits. In the end, the technique results in a story that makes us happy that silly little Wendell is wising up and makes us wish we were as well.

“The Unfathomable Sisterhood of Ick” by Charlie Jane Anders has a resolution I didn’t see coming and could not have enjoyed more. Mary suffers after the breakup with her boyfriend and so Mary’s best friend Stacia suggests that it would really make Mary’s next relationship easier if they took the boyfriend’s good memories of Mary and implanted them in the head of the next guy. That way, he’d know what Mary liked. Mary goes along with it and Stacia steals the memories and implants them into herself to see what it’s like to fall in love since she hasn’t ever had that experience. It goes poorly for Stacia and Mary nurses her back to health in a way I truly did not expect, but was perfect and made complex points about romantic love, the love one feels in a friendship, loyalty, memory, and more. Pleasingly layered.

*

“Dim Sun” by Maria Dahvana Headley

“Dim Sun” by Maria Dahvana HeadleyReviewed by Cyd Athens

“Dim Sun” by Maria Dahvana Headley is reminiscent of Douglas Adams’ Restaurant at the End of the Universe. The tale takes us to a very special Dim Sum restaurant where the cart features such unusual delicacies as Comet Ice and Io’s Moonlight. Here, they are literal offerings, not just fancy names. The narrator, Rodney, is invited to dine with his food critic friend, Bert Gold. Neither man is expecting Bert’s ex-wife, Harriet, the President of the Universe, and designer of technology that “made climbing through the space-time continuum as easy as climbing through a bathroom window,” to show up. Nevertheless, she not only shows up, she also joins them at their table and commandeers the dining experience. What follows is a course-by-course story of betrayal and revenge that leaves one hungry for dessert. The evocative visuals here are worth the read.

Dr. Leila Ghufran, the narrator of Amal El-Mohtar’s “The Lonely Sea in the Sky,” is a planetary geologist who is allegedly exhibiting signs of an obsessive disorder. The story is told in the first person point of view against a backdrop of songs and stories related to the theme of diamonds. The disorder, adamancy, is brought about by the doctor’s work with Lucyite—a diamondlike substance from Neptune that humanity discovers can be used for teleportation. Ghufran’s condition advances as more of the Lucyite is pressed into use. Eventually, the ascendency of the Lucyite and the doctor’s descent into the madness of her condition reach a critical intersection. This tale synergistically tackles two parallel storylines, neither of which would be particularly interesting alone.

In “A Burglary, Addressed by a Young Lady,” Elizabeth Porter Birdsall gives us Genevieve Tadma who, for her debutante raid, her entry into Society, has her heart set on burgling young James Yendaria. Unfortunately for Genevieve, her mother disapproves. There is strict etiquette about if or when it is appropriate to steal from your social inferiors, equals, or betters and Lady Tadma will not tolerate it being broken. During Genevieve’s dutiful burgling of a target who was selected by her parents—one in whom she has no interest whatsoever—fortuitous circumstance brings her both a rival and a solution to her problem. The most speculative bits here are the gadgets, giving this tale the feel of a mash-up between a contemporary black-ops mission and a debutante ball.

K.C. Norton’s “Canth” is a special sea-faring ship. It belongs to Captain Aditi Pearce. At the core of its perpetual motion engine is her mother’s heart. This story is reminiscent of, and gives a nod to, Melville’s Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. Canth has abandoned Captain Pearce who has hired a small boat to follow and retrieve her vessel. Were it not for the question of why the ship left in the first place and the mysterious stranger who suddenly appears and claims to be working with her father, who is in search of a mythical sea monster, Pearce would have an easier time of it. However, it is through, or perhaps in spite of, these challenges that Pearce grows less despondent and more passionate. This is a high seas romp with the requisite fantastic creature.

“They Tell Me There Will Be No Pain” by Rachel Acks is an extra story in the Limited Edition of this Special Edition of Lightspeed. In it, we follow a futuristic soldier who is being discharged after three tours of military service. As part of the separation, she has to “return all government property issued to you upon entry, including all surgical and neural enhancements.” This includes a “Tactical Analysis and Oversight Guidance (TAOG) system” that she named Phoebe in honor of her dead older sister, who died in a terrorist attack when a religious fanatic, acting in the name of Jesus Christ, spaced ten thousand people from a habitat on Juno. The tale follows this soldier who, even after her enhancements have been removed, still hears the TAOG’s voice giving her direction and authorization to kill. She seeks help from the era’s VA, and they insist that nothing remains of Phoebe, the TAOG, so it must be all in the soldier’s head. This well-done story about war, and the traumas that both cause and come of it, is an excellent read.

* * *

Non-Fiction

Response and commentary by:

Cyd Athens and Martha Burns

Cyd Athens–

“Women Remember” is a round-table interview facilitated by former SFWA secretary and vice-president, Mary Robinette Kowal. In it, Ursula K. Le Guin, Pat Cadigan, Ellen Datlow, and Nancy Kress discuss this question: “How do you think science fiction has changed, either as a genre or as a culture, from when you started in the field?” As is to be expected with such a discussion, there are not only anecdotal thoughts and perspectives, but also sidebars. Some of the tangents cover such ground as the rise of fantasy as a genre, and how this impacts science fiction. Also discussed is how some mainstream authors, regardless of gender, refuse to label their writing as science fiction lest their reputation be “tainted” by association with the genre. Ageism and its prevalence at science fiction conventions is another thread here.

In some ways, this is a discussion much like those concerning faith versus science. Here, gender inequity and the perception that female speculative fiction authors could somehow destroy speculative fiction faces off against facts like the increased diversity in the genre. Like the faith versus science debate, each position has thought-provoking points. That such a discussion appears in this issue is both expected and, in its own way, preaching to the choir. However, it does not appear to be the interviewer’s intent to convert readers. Rather, this is an opportunity for readers to engage in voyeurism while some of the genre’s grande dames converse about their experiences and discuss their thoughts on how much the genre has, or hasn’t, changed in their lifetimes.

To that extent, it is an updated version of a similar interview, “Women Writing Science Fiction: Some Voices from the Trenches” which can be found at http://www.sfsite.com/fsf/2008/sl0810.htm. That discussion, facilitated by Susan Elizabeth Lyons, included some of the same names found here. It was a compilation of the answers to four questions that Lyons sent out to thirty-one new to established “women writers who write or have written in the science fiction genre.”

In the Lightspeed interview, Kowal states up front that, “It feels very much like a case of ‘the more things change . . .’” Combined with the broad spectrum of topics covered, including how the genre is perceived by mainstream writers as well as an anecdotal look at historical gender inequity within the genre, one could take Kowal’s statement to mean that, as is often the case with social issues, the degree of oppression—intended or not—and under- or mis- representation of certain groups within the speculative fiction genres is decreasing. And the pioneers who get in on the front end make it easier for later generations. This makes the meme of anyone “destroying science fiction” a metaphor that acknowledges not only how much of a “good old boys” club the genre may have been in the past, but also how diversity has been welcomed, albeit perhaps grudgingly at first, and is now the rule rather than the exception. Think Rosa Parks. Think Billy Jean King. Because the women, minorities, and other writers who refused to be excluded persevered, the speculative fiction genres are that much more open to any who wish to make themselves at home and claim the genre as their own. If this is true, it is as it should be and this reviewer wholeheartedly welcomes the “destruction.”

*

Martha Burns–

Jennifer Willis‘s interview with Kelly Sue DeConnick addresses, among other issues, the representation of women in comic book art. DeConnick, who is a comic book writer, notes that “the male figure, the male superhero, is idealized to communicate the idea of strength. The female figure is idealized to communicate the notion of sexual availability.” This excellent point challenges the view that cheesecake is not sexist in any way, just pretty women. It’s a noteworthy point and an intriguing interview that gives special insight into issues of gender for both creators and readers of comics.

“How to Engineer a Self-Rescuing Princess” by Stina Leicht is an amusing reflection on Leicht’s journey to science fiction from an interest in the way mummies were prepared (hook in noses to draw out brains, the good stuff) to Star Trek and its first interracial kiss which was, coincidentally, the first episode Leicht ever saw. The piece makes the larger point that whatever way the dominant culture represents women, girls and women can find respite in science fiction. The piece contains a must-see recommended reading list.

“The Status Quo Cannot Hold” by Tracie Welser reflects on the guest speakers, panelists, and award recipients at The Sally Miller Gearhart “Worlds Beyond World” Symposium on the subject of Feminist Utopian Thought hosted by the Center for the Study of Women in Society at the University of Oregon. This piece surveys extensive ground as those who directly participated in the symposium addressed many topics, including a take on the sense in which women are destroying science fiction or what that means. Leicht reports award recipient Kathryn Allen making the very good point that if Frankenstein is the first science fiction novel, women have been the makers of science fiction from its inception. Also addressed is whether a feminist discussion in science fiction is too political. Vonda McIntyre’s response to this is an emphatic no. I’d paraphrase the take-away of the symposium overall this way: speculative fiction is the home of brainy themes and if we can use the form to address and explore our relationship to, say, technology, certainly we can use it to address and explore our relationship to gender and the sense in which gender equality is a component of a feminist utopia. Not to be missed, the reading list at the end alone is worth a look.

The short piece “Screaming Together: Making Women’s Voices Heard” by Nisi Shawl makes the simple point that to increase women’s presence in science fiction, they must get their work out there. Shawl makes practical suggestions to that end and emphasizes the need for deadlines and awareness of the women-friendly publications out there. Again, the resources listed are an important reference for any writer.

* * *

Personal Essays

[Editor’s note: The Personal Essays section was thrown open to the entire staff. Anyone might choose any essay or essays they so desired without restriction. The result is that with 28 personal essays some have been doubled up on, while others have gone without comment. This is just the way the process shook out.]

Harlen Bayha–

Kat Howard’s essay, “Writing Stories, Wrinkling Time” recalls her first experience reading science fiction. She saw her feelings and perspectives in the female characters at the heart of A Wrinkle In Time and looks forward to a time when having such characters leading the action isn’t the exception, but the rule.

In “Women are the Future of Science Fiction,” Juliette Wade recounts her story of becoming a science fiction author and the support she received along the way, even though her sciences of choice are the less-common linguistics and anthropology. She believes that in the future, the “soft” sciences of language and culture will take science fiction places it has never gone before, into explorations of diversity, feminism, and cultural power that will reinvigorate the genre.

Harlen Bayha loves to eat green smoothies, delicious salads, and eggs with hot sauce. He believes championing the diversity of human experience makes for good business, great stories, and a human race we can all be proud to take to the stars.

*

Chuck Rothman–

Reading through Kristi Charish’s essay “For the Trailblazers” in the June “Women Destroy Science Fiction” issue of Lightspeed, I was reminded of a comment made by Gene Miribelli,* who taught my graduate English writing workshop thirty years ago. He wrote literary fiction, and said, “The good thing about science fiction is that your work is judged on its merits.”

Charish says that she is “a woman in the fields of science and science fiction who has never dealt with the overt discrimination so many other women have.” And while sexism in the sciences is well documented, in science fiction editors are (and always were) interested in a good story, and not the gender of the writer. Susan Linville wrote a couple of articles crunching the numbers and finding that the percentage of each gender in the table of contents tracks with the percentage of submissions by each. No gender has a monopoly on good stories and no editor who wants to succeed is going to turn down a great story simply because it was written by a woman.

So are women destroying science fiction? It’s a silly concept, but to take is seriously, it depends on the oldest of science fiction fandom tropes: how do you define science fiction?

In the beginning, the genre took on any speculation, so long as it was presumably based on science (or superscience). Some of the greatest writers of the genre were willing to ignore the science in favor of what made a good story — even if the science was nonsense. Heinlein’s “The Green Hills of Earth,” for instance, postulated a vision of Venus that was known to be wrong when he wrote it. The Foundation Trilogy is based upon “science” that is nonsensical and is far more influenced by history than scientific progress. A. E. van Vogt was never one to care about scientific accuracy, yet he was one of the most popular authors of his time. And then there’s Ray Bradbury . . . .

Nowadays, though, there is a vocal subset of fans who believe that only hard science fiction is “real science fiction.”** The social sciences are scorned. Scientific accuracy is king.

The “women destroying science fiction” trope is part of this narrowing of focus. The argument not only stereotypes women and their writing; it also stereotypes the entire genre.

Science fiction – by male and female writers – is growing up. The process isn’t new: I recall the fuss over the New Wave in the 60s, which involved authors trying to include experimental literary techniques in their stories. Despite the brouhaha, it did move the genre further into thinking about literary values.***

This evolution is continuing, and many who prefer to read “old fashioned” science fiction find the change disturbing. They aren’t happy if the story focuses on the emotions of the characters so that the sense of adventure (and the science) takes a back seat.† But that is what the genre has always done: show how people are affected by the future.

The fact is that there were always women writing SF. The numbers were minuscule in the beginning, but have grown over the years, as more women are exposed to the genre. But by the late 50s, you had women like Evelyn E. Smith, Mildred Clingerman, Andre Norton, Leigh Brackett, C. L. Moore, Zenna Henderson, Judith Merril, Marion Zimmer Bradley, Katherine Maclean, Rosel George Brown, Pauline Ashwell, Kate Wilhelm, Carol Emshwiller, Margaret St. Clair, and Anne McCaffrey, with many others starting to appear regularly, and as time went by, more and more women were showing up in the magazine pages. In the 70s, women began entering the field in earnest and the idea of a woman writing SF stopped being a novelty. I always thought that was great for the genre, and it continues to be so. Charish is absolutely right in celebrating these trailblazers, but their most important part is choosing the path, not the obstacles on the way.††

Will there reach a point where women and men consistently appear equally in the table of contents of science fiction magazines? It all boils down to the slush pile, and the slush pile is not evenly distributed right now for one simple reason: writers write what they love.

If you ask any writer about what inspired them, they will say, “I read this book and fell in love with it.” If they love science fiction, they will write science fiction. If they love fantasy, they write fantasy.††† But if science fiction leaves them cold, then they won’t write it – or write it poorly. So far, more men than women have fallen in love with the genre. That may change, but it’s anyone’s guess as to what can create this change.

The trick to even out the distribution‡ is to make more women fall in love with science fiction. Will more women SF writers help? It couldn’t hurt, but I believe most people fall in love with the genre because of the stories, not the gender of the author.

But, really, is the goal to have an equal number of men and women in the table of contents? Or is it to fill a magazine with the best stories available?

Because if it’s the former (excluding the occasional theme issue), then what Miribelli said is no longer true.

Chuck Rothman’s novels Staroamer’s Fate and Syron’s Fate were recently republished by Fantastic Books.

Footnotes:

*He’s had several stories in F&SF, Asimov’s, and elsewhere in the past few years, but back then he was a mainstream writer with a couple of literary novels out. I like to think I had some influence in having him try SF.

** I’m talking about those who are putting forth actual critical objections. Those who attack women writing science fiction just because they hate women in general are beneath contempt.

***Not that there weren’t authors writing literary SF before that.

†I’ve seen arguments that when woman write science fiction, it becomes romance. The only way you can believe this sort of nonsense is if you never actually read anything by women.

††Not that there weren’t obstacles, but they were the same as for any writer.

†††I subscribe to the belief that science fiction is a form of fantasy (with a “scientific” explanation), anyway.

‡Whether this is a desirable goal I leave to others to debate.

*

John Sulyok–

The title of June 2014’s special issue of Lightspeed is “Women Destroy Science Fiction,” a title that is at once both clickbait-oil-on-the-fire and also a positive forum for lively discussion. The former version of the title implies that women, as a gender-aligned collective are somehow tarnishing the legacy of good science fiction, possibly by forcing out the science and infusing fantasy or, god forbid, romance elements. The latter version of the title suggests that women—and specifically women—have destroyed the “old boys club” that was SF, and have opened the door for new themes that explore gender roles, sexuality, and changing society. What the title, then, ultimately accomplishes is to stir a pot that may exist more as a meme than cold, hard fact, and also to diminish the work of male authors who also strive to seek new frontiers of discussion.

Anne Charnock’s essay “Not a Spaceship, Robot, or Zombie in Sight” falls into that devil’s advocate version of the title that suggests women are not welcome on the publishing side of science fiction. The essay is short and without anything substantial to state on the topic. It is something you would see as an anecdote on a late-night talk show, her struggles early on in her writing career when she had to juggle her time among “art practice, raising two sons, getting involved with community carbon-reduction projects.” It is a pragmatic line with just a hint of martyrdom. She goes on to say how in the UK at the time “women SF writers were struggling to secure publishing contracts,” which may very well be true, but then many men probably had the same problem. Charnock’s essay is filler that will only appeal on a biographic level.

Pat Murphy’s essay “Your Future is Out of Date” falls into the more positive category, although with one glaring flaw. She begins by recanting her youthful days in church, staving off the boredom by inserting herself into the books she had been reading. This was always especially difficult because in the 1960s there rarely were SF stories with female characters who weren’t “mothers or helpers or secretaries or in need of rescue.” Murphy came to believe that fiction writers had power over their readers for the duration that they were reading the story. And she made it her goal to “introduce [the reader] to different possibilities,” and that would mean “the destruction of science fiction as we knew it.” This is the positive form the title “Women Destroy Science Fiction” can take, where it means that there are good intentions at work to grow and expand the medium. And it’s hard to argue that momentum doesn’t usually come from the marginalized, but to pick and choose women as the Martials reduces the role of other groups like the LGBT community or racial minorities. The flaw in her argument, however, is that she begins by stating how she’d daydream of being in the stories, but those stories didn’t contain fulfilling female characters. The catch is that everyone likes to picture themselves as the hero, and that those stories were written by men and, for the most part, for men. Publishers knew who their audience was, who would be buying their books and magazines. Women weren’t the audience. Times change, audiences change, and so content changes. Yes, pioneers are required, but on both ends of the spectrum. And this, then, is the important part. That science fiction isn’t what it once was, and that people from all walks of life have injected new life into the discussion, not just women.

*

Louis West–

Kameron Hurley’s “We Have Always Fought” talks about the truths of cannibal llamas and how such “truths” can become so ingrained in individual and cultural psyches that actual reality becomes myth. Myths such as that of the Great Men of History taught in school. Reality is that women have always fought in resistance movements and wars, sometimes making up 20-30% of the fighting forces. But myths become reality when everyone is complicit in the great lies, telling ourselves that it must be true because everyone says it is. “It’s easier to tell the same stories everyone else does. There’s no particular shame in it. It’s just that it’s lazy, which is just about the worst possible thing a spec fic writer can be.” Women’s roles in life, society, education, politics, invention, science and even war have too long suffered the “truth” of the cannibal llamas. Change is long overdue.

“Reading the Library Alphabetically,” by Liz Argall, follows the author’s journey of self-discovery while reading the SF&F section of the library from A to Z. Her journey was lonely, given how few women authors graced the shelves at that time, and that “gendered marketing and schoolyard politics had made it clear I was not welcome.” Until she discovered Ursula Le Guin’s work, stories that gave her dreams to chase, dreams that she has realized, time and time again.

Maya Kaathryn Bohnhoff’s “Science Fiction: You’re Doin’ It Wrong” reminds us that “Humanity’s current problems . . . are not mostly hardware-related. They are software bugs,” i.e. are about the doers of science, not the science itself. And the single biggest complaint about female SF writers is that they write about the software problems. I find this somehow inanely shortsighted and deliciously droll.

*

Clancy Weeks–

In “Stray Outside the Lines” E. Catherine Tobler is clearly unhappy. I won’t dismiss her concerns as many males would, but I also think she is looking at it from the wrong angle. Is there discrimination and oppression in the publishing world? No doubt, but you can’t ascribe it all (or even mostly) to gender identification. Discrimination, oppression, bigotry, misogyny, etc., are all about power. Who’s got it vs. who wants it.

The common (inputyourfavorite) phobe is deathly afraid of losing their power—whatever power means to them—and that fear is fed by the entirely mistaken notion that any power the other gains is always at their own group’s expense. What the ’phobes don’t understand is that power and rights are not part of a zero-sum game. I don’t get mine from you, or vice versa.

This is where Ms. Tobler and a few others in this issue go wrong, as they adopt the same zero-sum attitudes as the people they hope to change. You can certainly assert your rights, but you can’t take them. Write what you want, the way you want, and hope there are enough good editors out there to see the value of a good story regardless of the gender identifications. That’s the real name of the game—change. There will come a time when editors who don’t hail from the white-male privileged will far outnumber those who do. On that day the tide will turn, and stories will not be bought for “audiences” but for the value of the narrative.

I’ve read several of the personal essays in this issue of Lightspeed, and so far, “Your Future is Out of Date” by Pat Murphy is the closest to how I feel about the subject. I can certainly sympathize (though not completely understand, white male that I am) with her outrage at discovering that the SF of years past was not written with the female reader in mind. In that area, at least, little has changed over the years even as the number of female authors in SF has increased.

Here’s the problem, though—writers (and I dare say all writers) write what they like to read. We are readers first, after all. While there is a large amount of overlap in plots, styles, format, etc., we all tend to stick with what we, as readers, prefer. There are certainly male authors writing so-called “women’s” SF, just as there are women who write great “men’s” SF.

I, myself, prefer Golden Age fiction, but in my own writing I try to root out stereotypes whenever they aren’t necessary to moving the plot along. And stereotypes are necessary at times, as things become stereotyped for a reason. Call it lazy writing or whatever, but every author uses familiar tropes as shorthand. We can’t write without metaphor, and the best are built on subjects that are familiar across many boundaries. So, yes, there will be characters that are nothing more than “the dutiful wife,” just as there will be characters that are nothing more than a “misogynistic douchebag.”

Even when I, as a male, try to create strong women without a hint of stereotyping I often fail miserably. Just as I can’t write about what it means to grow up Black in America, I can’t successfully write a story that is only from a woman’s perspective. What I can do is write her as I would write any male character and hope for the best. James Schmitz was excellent at this, and an author I try to emulate in this area. In fact, Ms. Murphy in her youth should have put down the Heinlein in favor of anything by Schmitz.

Things have changed for the better since the Golden Age stories of my youth, and I’m confident that in the near future the boundaries between “male” vs. “female” stories will continue to blur.

*

Charles Payseur–

Nisi Shawl makes the case for women needing to help women in “Screaming Together: Making Women’s Voices Heard.” Suggesting things like nominating female-penned books and stories for awards and joining organizations that assist female writers, the essay reveals some tools that women can use to help themselves be heard. As much as it is a well-written call to arms, I personally felt the essay lacked a clear direction for non-women advocates of diversity in speculative writing and reading. For women, though, the resources provided seem helpful and hopeful.

Christmas becomes a time of giving more than just toys in “Stocking Stuffers” by Anaea Lay, in which she recounts how the gift of a book from her father would end up having a profound effect on her. Focusing on the idea that the right book at the right moment can affect us all as readers and people, the short essay points to challenging our young people with science fiction not just by women, but by anyone who will get them to question their assumptions.

In “A Science-Fictional Woman,” Cheryl Morgan takes stock of some of the progress made by the world in terms of gender and acceptance, while at the same time calling for more work to be done. Challenging traditional ideas of gender binary, the prose is solid and moving, but I wish the last sentence would have echoed the non-binary argument in the rest of the piece.

The nonfiction in the issue really does run the gamut of experiences and voices. As a collection of women’s writing, it is well worth a read, because these are personal stories that people should see and understand, that should not be ignored or minimized. Most of the essays call for a tearing down of the walls defining binary gender roles and to end the “No Girls Allowed” mentality which exists culturally, and most do so eloquently. The destruction called for seems to be the continuing progress toward inclusion and understanding, a calling that many authors and professionals in science fiction already follow, though the issue points out some areas that require still more work and constant discussion. The essays celebrate women, but my largest complaint is that they mostly ignore other groups, leaving male, or intersex, or nonconforming writers out of the discussion and the destruction, at least for now. And that is where the issue let me down a bit, not in the stories and narratives and thoughts that it chose to include, but in those that it could have included and didn’t. By focusing the debate as women destroying science fiction instead of everyone destroying science fiction, the issue seemed to me to stumble close to the same binary thinking that many of the women writing for the issue argue against, and it is hard in the end to know exactly how to feel about that. I am left conflicted, because this is a good collection with some great pieces, but I hope that it is only the first part of a larger discussion to come.

Charles Payseur lives with his partner and their growing clowder of cats in the icy reaches of Wisconsin, where companionship, books, and craft beer get him through the long winters. His fiction has appeared at Perihelion Science Fiction, Every Day Fiction, Dragon’s Roost Press, and is forthcoming from Wily Writers Audible Fiction.

*

Ryan Holmes–

In Seanan McGuire’s personal essay “My Love Can Destroy,” the author writes about her origins into the science-fiction world: first as a girl who watched Doctor Who and Star Trek or enjoyed reading X-Men and daydreamed of riding unicorns only to be ridiculed by boys and girls alike, and second as an adult who was told by the ‘authorities’ early on and forever more that she was destroying the genre she loved. To these naysayers, McGuire makes no apologies. On the contrary, she boldly knocks down the gender boundaries boxing science-fiction into a finite universe, stares out into the dark expanse of unlimited potential, and goes where no man can deny. She didn’t choose the genre. It chose her, and in so doing found a visionary architect who sees a science-fiction future that welcomes both genders, and she eagerly goes to build it.

*

Martha Burns–

“We are the Fifty Percent” by Rachel Swirsky addresses the distinction between the perception vs. the reality of women’s presence in science fiction. The conclusion she reaches, reflecting on her own reading and editorial career, is that even in instances where women represent 50% of the writers or contributors (she does not say this is the norm, which the title of the piece suggests, only that she is addressing several concrete instances of 50% representation), the perception is that they are unfairly dominating. Given that perception, Swirsky encourages women to be more than a mere presence, but to be a very vocal presence. This is an enlightening discussion that addresses reader perceptions.

In “Are We There Yet?” by Sheila Finch, the author discusses concrete instances where she has encountered the perception that the categories of women and science fiction do not go together. She ends the piece with a positive interaction with an actual JPL scientist and the contrast is telling. Insightful.

“Writing Among the Beginning of Women” by Amy Sterling Casil cites William Faulkner’s claim in his 1950 Nobel Prize acceptance speech: “The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past.” She says that sticking to this credo has helped her maintain her courage during instances where her place as a woman in science fiction has been denigrated. It is a healthy motto and its place in a writer’s life is certainly worth pondering.

Marissa Lingen in “Join Us in the Future” describes how she left physics to enter the wonderful world of science fiction which, as an outsider, seemed not just woman-friendly, but woman-dominated. She cites Connie Willis and Lois McMaster Bujold, but the list of prominent female writers in science fiction is long and includes Octavia Butler, Joanna Russ, Ursula K. Le Guin, Mary Shelley, even reluctant members such as Margaret Atwood. The field appears sexist in no respect. What she soon found as a writer was that–a theme the authors in the anthology come back to again and again–the reality of women’s presence in the field and the popular as well as professional perception that they do not write science do not match. Yet the perception lingers. What’s with that? Perhaps if enough writers point out the silliness of the perception it will go away. Let’s hope so.

The very helpful “Toward a Better Future” by Nancy Jane Moore tackles head on whether science fiction is overtly sexist. She discusses the respect in which sexism often isn’t intentional. She quotes Carol Hay in Kantianism, Liberalism, and Feminism: “Most oppressive harms tend not to be the result of the intentional actions of an individual person, but are more often the unintentional result of an interrelated system of social norms and institutions.” Moore makes the point, however, that whether or not sexism is intentional isn’t really the issue. The issue is the effects of a social perception together with what gets published or even written. She says the only way to address women’s place in science fiction is to have an anthology like Women Destroy Science Fiction! where the issue of overt sexism is moot through the simple means of including only female writers.

According to Sandra Wickham, she didn’t experience sexism growing up with her brothers on the family farm, nor did she feel she’d suffered gender discrimination. She recounts in “We Are the Army of Women Destroying SF” that this experience continues to embolden her to be the Jedi warrior she’s wanted to be since she was a little girl. Yet she never denies the different experiences of other women. The piece points out how important it is that women who have had the benefits of equal treatment be a part of the discussion of women’s role in science fiction.

Gail Marsella sings the praise of how-to books on writing science fiction in “Read SF and You’ve Got a Posse.” She believes the practical advise will, at the end of the day, help writers focus on the craft itself and that it is all any female writer can do. On her view, sexism is there, but the only thing to do is to write. Writing as a sixty-year-old academic new to the field as a writer, she is yet one more welcome voice in a diverse conversation despite arguing that it is best to ignore sexism and carry on. The issue is how to make that possible, not whether it is best to do so.

O. J. Cade offers a wry commentary on the history of women’s inclusion in science in “Stomp All Over That.” It happened, she claims, because truth prevails. She notes that women’s contribution to science is an indisputable fact, so inclusion is about waking up, not about political correctness. She claims it’s impossible at this point to deny the contribution of women in science from Marie Curry to Henrietta Lacks, not to mention Ada Lovelace’s dual existence as the mother of programming and steampunk. The facts about women’s contribution to science fiction, Cade believes, will likewise prevail. The excellent point is made using the metaphor of shoes–too entertaining to be missed. Yet one also wonders about Cade’s optimism.

DeAnna Knippling asks “Where Are My SF Books?” She says that she only noted there were few science fiction books for her when she was reading books with her young daughter. At that point, she found that too many of the science fiction offerings were “a) All about Boys, b) Very Literary, or c) Not Otherwise Accessible to ME,” though she does end the piece by saying that YA science fiction with female leads is right now dominating the field, yet she worries having so many female leads keeps boy readers away. It’s difficult to know what exactly Knippling’s criticism is or if there truly is one. The accusation that YA science fiction with female leads will inevitably not appeal to boys is troubling as is the complaint that science fiction is too literary.

“Stepping Through a Portal” by Bonnie Jo Stufflebeam testifies to the benefits of making science fiction and fantasy known to teenaged girls. In addition, she discusses the dark side of science fiction and fantasy she found as a young reader and, no, she does not mean Lovecraft. She found that dark world in the critiques of female science fiction writers. She likens those critiques to the criticism of the teenaged boys in her AP English class who wondered why they had to read The Handmaid’s Tale. She hopes all of the women who found a home in science fiction and fantasy in their youths can help more young female readers discover the field. This is no criticism of Stufflebeam’s piece to say it’s her job to do anything besides write the best stories she can, but it would be lovely to have a plan in place to introduce young readers to the significant female presence in the field.

It’s exhausting to be a smart person, aware of the multiple levels on which things operate. “The Wendybird” by Stina Leicht clarifies what that’s like as a woman who writes, which is to say, what it’s like to be aware of the array of perceptions of gender in relation to literature. Should one write from a male point of view? Should one write sex scenes? Should one write for children? Why is a man congratulated for writing from a female perspective? Is this the assumption that he has secret access to an alien world? Leicht makes clear that this relentless self inquiry is destructive. She makes the case that creative people need freedom of, more than anything else, thought. I suspect this is likely an obvious point to many women, yet may be news to men. This is an issue that must be addressed and one is happy this personal essay addresses it in so clear a manner.

“I Wanted to be the First Woman on the Moon” by Sylvia Spruck Wrigley combines a painful childhood memory (being laughed at in class when she said she wanted to be the first woman on the moon), feminist reflection (why want to be the first woman to do x rather than the first person to do x?), and a testament to the liberation of science fiction (go to any planet, be any being, imagine anything). The essay makes one appreciate anew the power of science fiction to go where no one has gone before and transcend prejudice.

“Never Think of Yourself as Less” by Helena Bell is about Bell’s mother, specifically, the books her mother bought her as a young girl and the role reversal that occurred when Bell gave her mother a reading list filled with women writers of science fiction. It’s a loving testament to the conversation between children and their parents that can occur through books and how important it is to begin that conversation early on.

“Breaching the Gap” by Brooke Bolander addresses the difficulty of having access to the thoughts or feelings of another. Her view is that fiction bridges this gap. In the piece, Bolander recounts how Scully from The X-Files bridged that gap for her and started her devotion to science fiction, where our ability to connect with aliens is a metaphor for our ability to connect with others. The point feels right and questions the representation of science fiction as all in the head, never in the heart.

Georgina Kamsika believes science fiction is becoming more prominent now that the world sees how cool it is to be a geek. In “Women Who Are More Than Strong,” she mentions a respect in which science fiction needs to step up to the geek plate. She wants to read “Women who are more than strong, who have personalities, friends, lovers, and enemies.” The obviousness of the desire makes one wonder why it isn’t very often satisfied.

*

Cyd Athens–

According to Sandra Wickham’s personal essay, “We Are the Army of Women Destroying SF,” Star Wars is not science fiction. If this assertion by someone who “slush reads for Lightspeed Magazine” was meant to be sarcastic, that intention did not make it onto the page. That someone in a position to influence whether or not genre writers are published in a professional market would utter such a statement boggles the mind. The epic space opera that first hit the big screen in 1977 and has spawned a worldwide following, the series which includes six films to date with a seventh in the works, numerous spin-offs in both literature and animated film, not to mention the May the Fourth be with You greeting used by those in the know is not science fiction. After that shocker, this reviewer is concerned that if women are, in fact, destroying science fiction, they may be doing so not by writing it, but by refusing to acknowledge the genre, in all its forms, when they encounter it.

In “Stomp All Over That,” O. J. Cade uses shoes and humor to revisit the history of how women have branched out from “destroying” science to doing the same to science fiction. While some would rather have had these women barefoot and silent, it was difficult for anyone to disregard them when, “ Rebecca Lancefield was helping them see off Streptococcus in sequined, sequenced sandals and when Gertrude Elion was doing the same with leukaemia, with her toenails peeping red painted out of open-toed marrowbone shoes.” For this author, the bottom line is that, like they have been in science before, women bring value to the speculative genres. She encourages women who face naysayers to follow in their science predecessors’ footsteps and, “stomp all over that.”

“An ABC of Kickass, or A Partial Exorcism of My TBR/TBRA* Pile” by Jude Griffin is an alphabetical listing of important women, real and fictional, in the genre. Griffin is “an editorial assistant at Lightspeed Magazine.” Per the author’s footnote, “* TBRA=To Be Read Again.” The list is a hodge-podge mix with no common reference. Some of the entries are there because an author’s last name begins with a certain letter; some are there because an author’s first name begins with a certain letter; and, some are there because the title of a work, or name of an important feature in a work begins with a certain letter. Inconsistently, the entries have explanatory notes. The listing for Mistressworks, for example, simply says, “go” without indicating that Mistressworks is a website where books by women science fiction authors are reviewed or providing the URL, http://sfmistressworks.wordpress.com/. Rather than a personal essay, this is a reading list.

As general references for those who might be interested in seeking out more works by women science fiction authors, the Index to Female Writers In Science Fiction, Fantasy & Utopia: 18th Century to the Present which can be found at http://feministsf.org/authors/wsfwriters.html, the Wikipedia entry on Women in speculative fiction at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_science_fiction_authors, or the SFWA member directory at http://www.sfwa.org/member-links/member-list/ are all better starting points.

Closing Thoughts by the Editor

To get the obvious out of the way first, the notion that female science-fiction writers are destroying science-fiction is ludicrous, patently absurd. Those comprising that “subset” who, evidence indicates, prefer “hard” science fiction and are of the opinion that women can’t write it and therefore are ruining the specific type of SF they love, are not only sadly in error but occupy at most a miniscule 1% of the genre audience, if that. Their voice is naught but a lonely cry in the wilderness, rarely heard these days. One could easily put forth a strong list of women science-fiction writers who pen the “hard” stuff, and do it well.

To get the obvious out of the way first, the notion that female science-fiction writers are destroying science-fiction is ludicrous, patently absurd. Those comprising that “subset” who, evidence indicates, prefer “hard” science fiction and are of the opinion that women can’t write it and therefore are ruining the specific type of SF they love, are not only sadly in error but occupy at most a miniscule 1% of the genre audience, if that. Their voice is naught but a lonely cry in the wilderness, rarely heard these days. One could easily put forth a strong list of women science-fiction writers who pen the “hard” stuff, and do it well.

Though the ostensible raison d’être for the special “Women Destroy Science Fiction” issue of Lightspeed was just that—to respond to that ever-dwindling minority who complain that women can’t write “hard” SF, the evidence shows that those contributing to the June issue of Lightspeed have chosen to broaden the initial scope and introduce many of the usually talked about feminist issues now addressed within the SF community at large. Thus, my remarks will speak to a few of these general issues as well.

There has been much made of the question of diversity and inclusiveness in the SF field for any number of years now, especially in the past decade or so. Or rather the perceived lack of diversity and inclusiveness. The jump in logic that therefore SF actively opposes or restricts itself to fiction written primarily by white males I find as ludicrous as those who believe women can’t pen hard science-fiction. Yes, science-fiction in its earliest days and for decades was written for the most part by men and for a young male audience. The SF genre pulp magazines found they were publishing material that happened to appeal most strongly to a young male audience, and they continued to do so because it made their magazines profitable (in most cases; many went belly up quickly). But it did not in any way discourage anyone else – people of color, different ethnicities, or the female sex (or those with different sexual orientations) –from joining the party. There were many reasons then as now why all sorts of folks didn’t then or don’t now read or write in genre. But history shows that it is not something built-in, endemic, or internal to the current SF field itself. A look back at the field shows that the SF/F genre has been the most open and welcoming genre of perhaps them all, especially when one considers a wider overview and a little historical perspective.

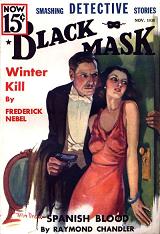

One historical example that springs to mind where the pulp magazines are concerned is the gold standard of detective pulps, Black Mask. It ran from 1920-1951, and as one might imagine its stories were written by men for a male dominated audience. In its 32 year pulp history there was only one woman to have written for the magazine, Katherine Brocklebank. I quote from the introduction to Brocklebank’s story “Bracelets,” which was one of the stories selected for inclusion in the 2010 magnum opus collection The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories, edited by Otto Penzler: “Katherine Brocklebank was unique in the history of Black Mask magazine […] In the first place she was a woman and, unless cloaked behind initials or a male pseudonym, the only one identified in the thirty-two-year history of Black Mask, even when it was under the control of a female editor, Fanny Ellsworth, from 1936-1940.” Was Black Mask a sexist magazine, purposely excluding women from reading it or writing stories for it, or a product of its time merely finding its audience and writing to that audience to insure a profitable product, regardless of who its readership was and who wrote its

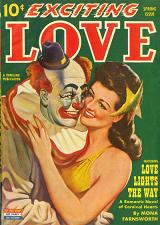

One historical example that springs to mind where the pulp magazines are concerned is the gold standard of detective pulps, Black Mask. It ran from 1920-1951, and as one might imagine its stories were written by men for a male dominated audience. In its 32 year pulp history there was only one woman to have written for the magazine, Katherine Brocklebank. I quote from the introduction to Brocklebank’s story “Bracelets,” which was one of the stories selected for inclusion in the 2010 magnum opus collection The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories, edited by Otto Penzler: “Katherine Brocklebank was unique in the history of Black Mask magazine […] In the first place she was a woman and, unless cloaked behind initials or a male pseudonym, the only one identified in the thirty-two-year history of Black Mask, even when it was under the control of a female editor, Fanny Ellsworth, from 1936-1940.” Was Black Mask a sexist magazine, purposely excluding women from reading it or writing stories for it, or a product of its time merely finding its audience and writing to that audience to insure a profitable product, regardless of who its readership was and who wrote its  detective stories? If one answers that it was indeed a sexist magazine, then consider that in the same general time frame as Black Mask’s 32-year pulp run, there were something on the order of 150+ pulp titles devoted to an overwhelmingly female audience; titles like Romantic Love Secrets, Secret Love Revelations, Lover’s Confessions, Hollywood Love Romances, Lyric Love Stories, Charm Story Magazine, Ardent Love, Navy Romances, Snappy Romances, Tales of Temptation, Cupid’s Diary, Exciting Love, Golden Love Tales, Love Adventures, and on and on. Were these random titles and over a hundred more sexist because the stories within their pages were written expressly with women in mind—regardless of who wrote them?

detective stories? If one answers that it was indeed a sexist magazine, then consider that in the same general time frame as Black Mask’s 32-year pulp run, there were something on the order of 150+ pulp titles devoted to an overwhelmingly female audience; titles like Romantic Love Secrets, Secret Love Revelations, Lover’s Confessions, Hollywood Love Romances, Lyric Love Stories, Charm Story Magazine, Ardent Love, Navy Romances, Snappy Romances, Tales of Temptation, Cupid’s Diary, Exciting Love, Golden Love Tales, Love Adventures, and on and on. Were these random titles and over a hundred more sexist because the stories within their pages were written expressly with women in mind—regardless of who wrote them?

The Love and Romance pulps were written predominantly by women for women, while the War and Western and Adventure and Detective pulps were written for men, and in cases like Black Mask, only one known woman wrote for it in its 32-year history. In pulps catering to women, they were almost exclusively written by and for women (a few men also wrote for the Love and Romance-type pulps). In pulps catering to men, the percentage of stories penned by and for men was even greater. It seems that, to a greater or lesser degree then, the lines were drawn in both directions almost equally. If one were to praise or damn one kind of magazine by today’s standards then one must do the same for the other kind of magazine; no double standards.

The science-fiction pulps were also a product of their time, no doubt about it. But though cultural assumptions and biases were present, they also spoke to, and about (as a general proposition only), something more universal—the imagination—which both sexes delighted in and shared; everyone likes to dream and fantasize. So how did the real-world SF field fare in the pulp era, that of the 1920s-1950s? When women finally discovered the field a few at a time as readers, then as fans and convention attendees—and then writers—did they find that discrimination abounded, that they were not welcome at SF meetings or fan clubs or conventions, or as writers within the pages of the SF/F magazines? The late, great, and much beloved Leigh Brackett had this to say when I asked if she encountered any discrimination in the SF field due to her being a woman:

“TANGENT: Leigh, there were very few women writing science fiction during the 30s, 40s, and 50s. Were there any special problems you had to face being a woman?

BRACKETT: There certainly wasn’t with me. They all welcomed me with open arms. There were so few of us nuts that they were just happy to receive another lamb into the fold. It was simply that there wasn’t many women reading science fiction, not many were interested. Francis Stevens sold very fine science fiction stories to Argosy back in 1917, back around that period.

HAMILTON: Her name, you see, could have been a man’s name and Leigh’s name could have been a man’s name. Catherine Moore, who wrote SF long before you did, and a dear friend of ours, wrote under the name of C. L. Moore. Now, I don’t think there was much real bias on the part of women’s libbers–

BRACKETT: I never ran into any. On some of the first few stories I sold people would write into the letter columns and say Brackett’s story was terrible, women can’t write science fiction. That was ridiculous, there were women scientists you know, there’s no problem there. What they were complaining about was that I didn’t know how to write a story (chuckling). When I learned a little better I stopped hearing this. What they were complaining about was the quality really, not…you know. The editors certainly, there was never any problem with them.” —Tangent #5, Summer 1976