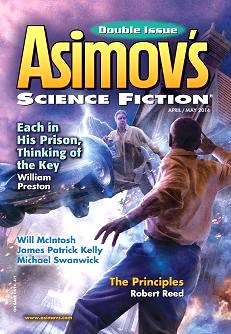

Asimov’s, April/May, 2014

Asimov’s, April/May, 2014

Reviewed by Louis West

“Each in His Prison, Thinking of the Key,” by William Preston, is a powerful tale of a veteran of the American war in Iraq and his struggles to reconcile the opposing realities of the violence, desperation and grief inflicted by the war versus the seemingly unaffected life of those back at home.

Jimmy was a military interrogator trained to get inside a prisoner’s head and “realign his will” just by imaging it. Of course, the procedure had risks and rarely worked when his and the prisoner’s worldview and beliefs varied drastically. Still, he’d been called in to crack a prisoner, a big man they called Methuselah (spelled Methusaleh in the story), held in a “non-existent” facility in the American Southwest. It’d taken a team of twenty to subdue this prisoner and bring him in, and his dossier was full of anecdotes about what he could allegedly do—essentially anything and everything—plus a long history of interjecting himself into human history over the last century. Myth? Reality? Jimmy became increasingly uncertain the longer he spent with his silent prisoner.

After applying all his skills, Jimmy fails to learn anything from the prisoner but does discover some frightening things about him. They think Methuselah waits, cross-legged seated in his cell, when in truth he is levitating, almost, balanced on just the edges of his feet. It’s only when Jimmy finds himself staring into the depths of a massive hole in the prison yard, dug by some strange subterranean beast, into which Methuselah had escaped, that Jimmy realizes that his prisoner had been in his head all this time, not the other way around.

Skip forward in time to where the story actually begins with Jimmy going on a weekend adventure with his girlfriend of six months to meet her friends. His experience with the prisoner broke him, left him empty. After the therapists piece him back together, he still misses his lost self. Everywhere he goes his sense of the world is constantly overlaid by images, thoughts and sensations of his time with Methuselah. Jimmy can’t tell his girlfriend, Bekka, anything about his military service, but she seems to understand.

The story paints a stark contrast between the everyday existence of Bekka and her friends and the soul-wrenching memories Jimmy had of his time with the prisoner. Life seems mundane and unresolved until Jimmy catches a news story about a man remarkably similar to his escaped prisoner. Then he sees “a dark passage and a silhouetted figure seated at the end, lifting his head, eyes open and daring him to look back,” and the chase is on. Jimmy hunts his past, trying to rediscover purpose, as he follows strange event after event across the country, interviewing people about what and who they’d seen. It didn’t take Jimmy long to conclude that Methuselah was back, saving people from impossible natural disasters like multiple giant sinkholes swallowing large portions of a town. Finally, Jimmy comes face to face with Methuselah, and the Old Man offers Jimmy a choice that will change his life forever.

This story is quite compelling, and I was enthralled by everything it turns out Methuselah is involved in, but can’t say due to spoilers. I would, however, highly recommend this and all the other stories in Preston’s Old Man sagas. Very good reads.

Robert Reed’s “The Principles” is a low-key alternate history story set in a late 20th century Earth where the West has fought the Mongols for 1,300 years. Western women rule and aspire to be doctors and presidents while men to be heroes during their ten year’s mandatory military service. Quentin, who is the son of a Hero and thereby excluded from having to serve, works at a local American Midwestern factory in spite of having a Biology degree. Among the humdrum normalcy of his life, he has an affair with Sandra, a teacher twice his age.

The story spends a lot of time plumbing the rich diversity of this alternate world’s culture and history with Quentin’s life and love affair as a guide to the topics explored.

Intellectually interesting but absent any particular plot tension. Then, Quentin learns that Sandra has an adult son, Theo, an important dissident, she calls him, but Quentin can only think “traitor.” In this world of incessant war, the Federals are ever vigilant against anything and anyone that might upset the domestic peace. War protestors are not tolerated. Now Quentin fears for his safety, and paranoia sets in. The days follow. No Federals come crashing down his door. Only when Theo finds him does he learn that Sandra is a leader of the dissidents. The decisions he makes to help rescue Sandra, then whether or not to run away with her ultimately demonstrate what kind of man he is.

This tale rambles a lot, and I found it difficult at times to follow. While the complexity of this world is intriguing, I never really appreciated Quentin, especially with his passive-aggressive approach to life’s challenges. I did feel pity for him, though, because I would hate to be stuck in a similar conundrum. Nonetheless, I had hoped for a more satisfying ending rather than a dose of mundane reality.

In “Of Finest Scarlet Was Her Gown,” by Michael Swanwick, Su-Yin follows the Devil’s limo, with her father the General inside, intending to find a way to free him. At first Su-Yin’s ignored, until she starts being nice to everyone and, Devil forbid, making life a bit easier for those around her. Then the Devil challenges her to remain a virgin for an entire year yet go out with whomever the Devil chooses for Su-Yin to date. If she wins, she can leave with her father. If not, then she must go back by herself. The Devil even gives Su-Yin a nice penthouse and a personal tutor, Leonid, whom Su-Yin suspects is gay, to teach her the rules of hell. Su-Yin endures a rocky year, subjected to the pawing advances of the uncouth, and the slick charismatic allure of beautiful men. And she almost makes it, betrayed at the end by the one she least suspected. However, she gets her own form of revenge when she returns to the mortal realms. An entertaining read.

Matthew Johnson’s “Rules of Engagement” is a story about a story, told from the outside by someone (“A Reporter at Large”) trying to piece together key information to explain what had happened. But “what happened” isn’t revealed until the very end. Consequently, the telling wanders between three different pasts until it all converges. This made it hard to follow, although it more accurately portrays the disconnectedness that passes for reality for the main characters, recent veterans of American anti-terrorist wars in Yemen and Somalia.

Military personnel often suffer a dualistic sense of the world after returning to civilian life (to oversimplify for the sake of this discussion, not to minimalize the actual impact on our men and women of the armed services). For Bishop, Cervantes and Hollis, it was particularly difficult because they each had brain implants that gave them remote control over military drones and raptors. Something inexplicable happened to them during one mission, although the military consistently denied any problems with the implants. This story follows the fight of these three vets to survive in combat, adjust to the limbo of not knowing whether they would be reassigned or retired to civilian life and ultimately, when under extreme duress, finding themselves unable to distinguish in which reality they existed. PTS? Of course, but aggravated by the unknown effects of dynamic implants trying to adapt to a constantly changing human brain. Good food for thought, especially as military cyborg implants are already being researched. Recommended.

“Scout,” by Will McIntosh, follows Kai, a scared, 13 year-old boy, a war orphan due to an invasion by giant, faceless starfish (the Luyten) that can read human minds. Kai is cold, hungry and alone, trying to survive but failing, until one night a voice calls to him in his head. A Luyten scout—not a warrior, it insists—injured and afraid, helps Kai survive in exchange for food and secrecy. Then Terran soldiers close in, and Kai must decide whether or not to betray his new friend.

There’s something about a story from the perspective of a scared, 13 year-old orphan that is irresistibly compelling. Our children should never have to endure such hardship and horror, but war, whether visited upon ourselves or by others, always harms the innocent. When does an enemy become a friend, and are we enemies because we refuse to be friends? These are two of the hard questions raised by this story to which Kai doesn’t know the answers. But we should, and that’s why this story is so good, because it doesn’t talk about heroes and villains, just those trapped between. Highly recommended.

In Fran Wilde’s “Like a Wasp to the Tongue” we encounter a team of briggers (military prisoners) who chose rehabilitation instead of the brig by working on an exoplanet terraforming project. The planet’s almost ready for colonists, and the briggers in their boredom are daring each other to see how long they can keep a wasp in their mouth without getting stung. Bad idea and even worse results. One man dead and others with nasty welts. Rios, the doctor/medic has to patch up the wounded and figure out what’s going on. Then the captain comes back, dying from bad burns, and the corporate bigwigs he’d been touring around the site gone. In spite of the planet’s mineral wealth, the corporates recently discovered that it also had a native fungus that travels as fast as man and readily infects humans. The briggers were expected to die slow and horrible deaths, so corporate abandoned them. But Rios had other ideas which involved using the genetically engineered wasps in ways for which they were not designed. A solid, enjoyable piece with plausible science, characters ready to kill each other and a tension-filled plot. Definitely recommended.

“Slowly Upward, The Coelacanth,” by M. Bennardo, follows the progress of a human soul that had been saved from an extinction event by being transplanted into a Coelacanth. But to regain her humanity, she must wait until the survivors return and transfer her back up the animal chain. At least that’s the idea, but it doesn’t always work. Overall, an interesting concept, but the story lacks any tension or challenge for the protagonist to survive.

Kim J. Zimring’s “The Talking Cure” starts with the flashback–“I’m crouched by her face (my mother, we later learn), mouth close enough to kiss, waiting for a breath that never comes”—that sets the tone for the story. This 1st person POV story is about a man who survived Nazi-occupied WW2 Vienna, and now, over a half century later, has been called by Sotheby’s to help authenticate a work of art. The process involves complicated equipment that allows his memories to display on a screen. From these, Sotheby’s will search for when he visited Freud as an autistic child to see if a particular painting did indeed hang in Freud’s office, thereby proving provenance, i.e., who owned the painting when. At first the memories verify what he’d always known. Although he’d been autistic, he’d changed out of fear and necessity, because he knew what the Nazis had planned for “mentally disabled” children. [Although I’m not sure how a four year-old would know this and the story doesn’t say.] He could talk or die. He chose to talk. Then the memories showed things he didn’t recall: his mother’s sister. He didn’t know she’d had one. And a cousin that looked something like him, whose father was a Jew. As the memories continued to surface, his world turned upside down. The woman he’d called “mother” for so long, wasn’t his mother, and he wasn’t who he’d thought he’d been. But worse was the price these two sisters paid to save him from the Nazi’s, an awful, mind-numbing price.

I had to read this story several times to capture all the twisty components to the plot and figure out who was really whom, especially after the gut-hit from the ending. Absolutely marvelous, especially once I finally understood what had happened to the main character’s real mother. Exceptional.

“Dolores, Big and Strong,” by Joe M. McDermott, is a story about June Jimenez Nguyen, Jujube, who lives with her mother and step-grandmother, Dolores, on a goat farm. She hates her lonely life, the smells of goat shit and cat pee, and hates her grandmother because every night she has to open a shunt in her arm to swap blood with her. Dolores suffers from Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s and has a rare blood antigen, Duffy, matched only by Jujube’s. The daily blood transfusions help keep Dolores’ symptoms from getting worse. This is a gritty, hopeless tale of a teen trapped in her life, the events that led to her grandmother’s death that free her from that life, and her part in killing the man who caused her grandmother’s death; for ultimately her grandmother was only hers to hate. A harsh tale, but well told. It’s also interesting to note that research to-date has shown that people with Duffy blood antigens can show some resistance to certain types of cancers.

In James Patrick Kelly’s “Someday,” Daya is of the age to choose the fathers for her child. She lives in a sleepy town on a world colonized by humans that fled Earth two centuries ago. Now the rest of humanity has rediscovered them, causing old and new ways to clash. The focus of this story is reproduction, for evidently Daya’s people are the only humans still using sex to reproduce while the newcomers all have replaceable bodies. An interesting tale, although absent any significant plot tension or challenges to Daya’s purpose.