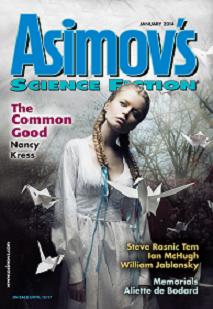

Asimov’s, January 2014

Asimov’s, January 2014

Reviewed by Colleen Chen

This issue of Asimov’s has three novelettes and three short stories.

The first novelette, “Memorials” by Aliette de Bodard, takes place in a future in which Galactic citizens can have facsimiles made of their memories on a microchip recording, allowing them to become Perpetuates after death and to go on living in a virtual universe forever. The Rong people are a group living among the Galactics, although their culture doesn’t believe that Perpetuates are truly continuations of the souls of the dead people.

Cam is a Rong female who procures these microchips for the Aunts—a group of women who pay Cam handsomely for her work, even though Cam suspects them of dealing in the black market for Perpetuate memories. Cam is eaten up with guilt over what she does and the lies she tells her pregnant girlfriend and her family about her career, but she feels trapped by her need for money. When she’s cornered by a policewoman who offers to reduce Cam’s time in rehabilitation in exchange for Cam helping track the Aunts for the police, Cam caves in—not realizing how little she knows what’s behind the web of deceit in which she lives.

It’s a question often postulated in science fiction stories, of whether a copy of a person’s memories—who they were during life—equates to that person. This story explores this question in a rich and skillful manner. The worldbuilding is superb, as is de Bodard’s ability to build tension, the feeling of a net slowly drawing close around the protagonist. The question of memories equating to the soul wasn’t answered, but the complexity of the story and the depth of the main character are more interesting here than the philosophical issues.

“Primes” by Ron Collins was my favorite piece of this issue. As in the previous novelette, the premise dealt with is a common one. In this future, every person is connected neurally to the Internet, and advertisers have honed their ability to target customers to the point that they can, within each customer’s own thought-interface, create “glide paths to the right store so smoothly they thought they got there all by themselves.”

Jersey Jones is a socially awkward man who works for one such advertising company. He begins to apply his ability to “push” people to get women to come home with him and have rough sex. Things go wrong when one such woman, out of the blue, leaps through Jersey’s window to her death. This incident opens up a murder investigation, which escalates in intensity as Jersey targets his next victim.

All the characters in this story are related somehow to various prime numbers; it’s through the discussion of their prime-ness, the particular primes they would be, that their personalities are unearthed to the reader. The story is packaged and unraveled in such a fascinating way—and along with the clever design of the story itself, there’s plenty of edgy emotion, philosophical questions, and a rather thrilling exploration of the shadow that exists in each person. I loved it.

“The Common Good” by Nancy Kress takes place 56 years after aliens came to Earth and destroyed all its major cities and most of the population in order to stop humanity’s path toward its own destruction. Zed is a seventeen-year-old boy who leaves his isolated farm life and his parents, both of whom live in terror of that day of destruction happening again. Zed becomes infatuated with a young woman, Isobel, who is the impetus behind his seeking out the energy dome—a place established by the aliens.

Once inside the dome, Zed discovers that the aliens have been training and teaching young humans how to heal the planet and wisely lead its people. Zed, who remains torn over the question of whether it was right for the aliens to murder so many people in order to save the whole, begins to learn the art of far-seeing, attempting to solve this question for himself.

The introduction to the story mentions that Kress wrote it partially to show “how people often have completely opposite ideas of what is in the best interests of humanity.” In exploring that dichotomy, she’s produced an engrossing, well-told story, seen through Zed’s innocence and the slow growth of his wisdom—which is almost more based on his connection to his heart than on that with his mind. The theme is not a new one, but the questions remain about what is the best path for humanity, and they are more relevant than ever.

“Extracted Journal Notes for an Ethnography of Bnebene Nomad Culture” by Ian McHugh details the account of a study of the bnebene, a species of nomads who resemble people but are much more plantlike. They are so different from humans that the narrator, an ethnographer who has received the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to do this study, must tiptoe around what she says and does. Misunderstandings can mean the difference between banishment and the making of her career.

The main source of confusion for some of the bnebene arises from their species’ having a true hive mind amidst brothers and sisters—shared consciousness that transmits any reaction felt by an individual to the group. The narrator encounters difficulties when she attempts to explain that she’s an individual without such “parts” of herself existing outside of her—a concept that greatly upsets the bnebene.

This story is unique in both format and content. The description of the bnebene is authentic, and the narrator’s characterization is perfect. The individual vs. hive mind theme was interesting to me, although other parts in this story went totally over my head. But that, too, gave it the flavor of a true ethnographer’s report.

In “Static” by William Jablonsky, something is happening tonight in space that NASA has been planning, or planning around, for years. Supposedly it will involve just an EM surge, but many people think that the world is going to end instead. The narrator’s wife, Soledad, is nervous and hormonal, an overprotective mother to a 9-month-old baby Oscar, and she is particularly anxious tonight. When the surge happens, the world doesn’t end, but time and space warp in a strange and localized fashion—on television or phone, they begin to receive snippets of transmission from past and future. They get calls about an older Oscar about things that will happen in the future, and then Oscar himself calls, progressively older each time. What they learn from that night about the course of the future is a mixed blessing and curse.

This piece makes an emotional, personal story out of a hypothetical scientific event. It made me think about issues of acceptance, willpower vs. fate, and what it means to live in the present. The story seemed to be more about the moral and emotional dilemmas arising from knowledge of the future than about character development—I didn’t really like or identify with any of the characters—but I found it effective and moving nonetheless.

“The Carl Paradox” by Steve Rasnic Tem is the one humorous story of this issue, and it stands well as a representative of science fiction comedy, as it is utterly hilarious. I don’t think I’ve ever enjoyed a time-travel story as much as this one. Using a time machine invented by his much smarter friend Hector, a fellow named Carl travels thirty years back in time to visit his younger self and warn him against marrying a certain woman. He creates no paradoxes in space-time because Hector had determined that neither Carl nor his younger self are important enough to change anything in history—that they are “insignificant variables,” no matter what they do. Because the older Carl forgets to bring the return device, yet another Carl appears, beginning an escalation of time-traveling Carls until their collective insignificance finally might become significant—or not.

I loved this story and read it twice in succession. Carl is a quintessential loser, the kind of person we cheer on but not so much that we mind an ending in which he doesn’t fare so well. The story is short and clever, the dialogue priceless, and all of it well worth the read.