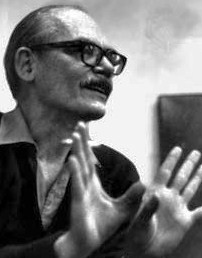

Tangent Online Presents:

An Interview with Frederik Pohl

(November 26, 1919 – September 2, 2013)

Interviewer:

Dave Truesdale

Location:

Howard Johnson’s Restaurant

Eau Claire, Wisconsin

(Midnight)

February 1, 1977

Interview originally appeared in Tangent No. 7/8, Summer 1977, and is reprinted here for the first time.

I had learned that Fred Pohl was engaged to speak at one of Wisconsin’s small state colleges in Eau Claire the evening of February 1st and was determined to interview him there. My ladyfriend and I drove nearly halfway across the state from Oshkosh, then sat through the talk where something like 30 students were in attendance. I was getting nervous because it was getting very late and we had to drive home. The talk ended and my hopes for an interview were fading. Fred then suggested we repair to the nearby Howard Johnson’s, get something to eat and do the interview there. We ordered our meals and ate while the tape recorder was running. It ran for well over an hour as we talked and talked. Sometime after midnight the recorder clicked off, we were all tired, and so agreed to call it a night. The separate checks came, but before I could reach for my wallet Fred made it clear that he was going to pickup the check, which he did. We paid the tip and drove Fred to wherever he was staying (I forget exactly where now, after 36 years.) It was a wonderful evening, getting to spend time with Fred and ending up with such a terrific interview. It was much more than I’d hoped for. Reading it for the first time, I hope you come away with it feeling much as I did — and did once again after working up this transcription, getting the chance to relive that night of so long ago. I was 26 years old in February of 1977 and had just discovered fandom and conventions a mere two years earlier, but much of that early period — and the memories like the one Fred gave me that night — they still seem very much like yesterday.

Special Introduction to Fred Pohl Interview

by Jack Williamson

(March 2, 1977)

Fred Pohl, more than anybody else I can think of, is the complete science-fictioneer. He tells in The Early Pohl how his world changed when he discovered — or helped invent — science fiction fandom. That was in 1933, when he had just turned 13. He quit high school as soon as he legally could, because he was more interested in what he was learning outside, most of which came through science fiction. His first publication was a poem, “Elegy to a Dead Planet: Luna,” written when he was sixteen and finally published in Amazing Stories for October 1937. By the fall of 1939, aged 19, he was editing two science fiction magazines of his own and buying his own stories for them.

I have always felt fortunate to have him for a friend. We met at the first World Science Fiction Convention, in 1939. In the fan feud that Sam Moskowitz calls “the immortal storm,” Fred, along with Don Wollheim, Doc Lowndes, Cyril Kornbluth, and a couple of others, had been excluded from the convention hall. I remember several enjoyable hours spent with them in a café across the street.

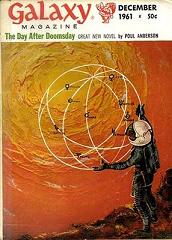

In the years since 1939, Fred has edited the Star series for Ballantine Books, the first original anthologies. He has edited Galaxy and If. He has edited the Ace science fiction line. Currently he is the science fiction editor for Bantam Books. He has been an agent; his Dirk Wylie Agency was once almost a science fiction monopoly. He has been President of the Science Fiction Writers of America. He has been a recognized futurologist and a popular speaker. Best of all, he has kept on writing. In New Maps of Hell, published in 1960, Kingsley Amis recognized him as a distinguished modern satirist. When I was receiving my Ph. D. a few years later, most of the commencement address came from Fred’s “Midas Plague.” His remarkable novel, Man Plus, seems likely to win awards in 1977. I think his new one, Gateway, is even better.

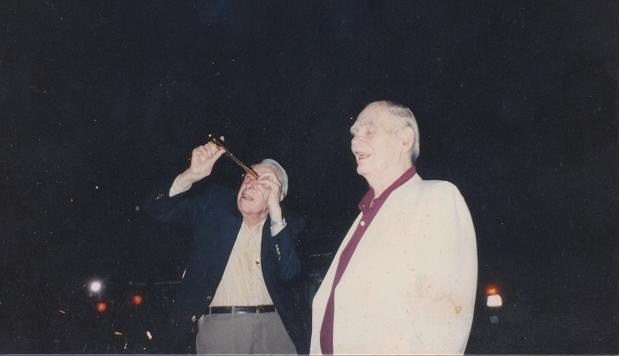

Through all these years, we have been good friends. During world War II, we were together in the Army weather school at Chanute Field. He has been my literary agent. We have published seven novels in collaboration, with an eighth in progress. I hope we are able to do many more.

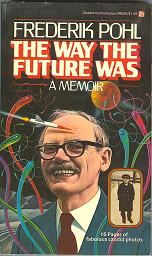

I like and admire him as a warm-hearted, ready-witted man, of many interests and vast abilities. Though his politics may be a bit more liberal than my own, that has never been a problem. I regret that I see him so seldom, because New Mexico is so far from New Jersey. He and Carol live there in a huge old house at Red Bank. In spite of all his travels and lectures and editorial duties, Fred still writes four pages a day. An excellent rule. His work in progress is an autobiography, which I am anxious to see.

{Jack Williamson and Fred Pohl, 1996, Campbell/Sturgeon Awards, Lawrence, KS}

TANGENT: When you became editor of Fictioneers, Inc. it was a far cry from the way things operate today. You don’t simply walk into a publisher’s office and say you want to edit one or more of his magazines and expect to be hired. How would one go about establishing oneself in the hope of eventually becoming an editor?

FREDERIK POHL: Yes, you can. You can walk in and say you want to edit the magazine. You may or may not get the job, but chances were not all that great back then either. It’s just a matter of luck. If you happen to apply for a job when they need somebody you may get it. If not, probably you won’t, because they’re not going to bother to call you six months later when there have been maybe twenty-five people applying in between.

TANGENT: They just don’t take a nobody, though. They had to know something about you, didn’t they?

POHL: Not really. They knew that I knew more about science fiction than they did, but they didn’t know how much there was to know so they weren’t aware that I didn’t know it all.

TANGENT: How would one go about making a name for himself today? Where would one start?

POHL: Get a job as a stock boy in a publishing company. That has worked with Jim Baen, who is now editor of Galaxy. Also Pat LoBrutto, who is the science fiction editor for Ace Books, and two or three others I can think of. Once you get into a publishing company the internal mobility is easy, comparatively speaking. Getting into one in the first place is sometimes hard.

TANGENT: What do publishers look for in an editor today – magazine or paperback?

POHL: Publishers look for somebody who they think is likely to make money for them, basically. If you convince them that you know what the market is, what the readers want, and that you can provide it for them…

TANGENT: Seems they want them to be knowledgeable businessmen.

POHL: Hmmm—yeah. They don’t expect editors to be too great as businessmen; they expect them to have a notion of what the readers of science fiction want.

TANGENT: What are the criteria for a good editor in your estimation?

POHL: That’s almost impossible for me to say. There are a lot of ways of being a good editor. The way that strikes me as being most commendable is to have pretty good taste for yourself and follow it. If you can tell the difference between what’s good and bad, in some reasonable way, and if you stick with it, sooner or later you’ll accumulate enough people who agree with you to make it successful.

TANGENT: Would you call Forry Ackerman “successful” because of the number of people he has buying Perry Rhodan?

POHL: I would call him very successful. It’s not the thing I’d like to do but Forry is able to make Perry Rhodan please readers, and there’s no way I could. I hate it to begin with, so I couldn’t possibly edit it.

TANGENT: What do you think of the magazine and paperback editors of today?

POHL: I have a great deal of vanity about my ability as an editor and therefore I don’t want to discuss anybody else. It takes quite a lot to edit a magazine, or for a book publishing company the way that I think is ideal – which nobody ever comes up to. But one of the things it takes is a lot of energy and a lot of willingness to go out and get things, not just sit and wait for them to happen but to go out and talk to writers and persuade them to write something, to suggest something they may do. And not too many of the editors of today are doing that. They must be aggressive in a useful way.

POHL: I have a great deal of vanity about my ability as an editor and therefore I don’t want to discuss anybody else. It takes quite a lot to edit a magazine, or for a book publishing company the way that I think is ideal – which nobody ever comes up to. But one of the things it takes is a lot of energy and a lot of willingness to go out and get things, not just sit and wait for them to happen but to go out and talk to writers and persuade them to write something, to suggest something they may do. And not too many of the editors of today are doing that. They must be aggressive in a useful way.

The other thing that I think is a little lacking is the willingness to take chances, to do things that nobody else has done. Some of the most successful things I’ve published have just fallen in my lap because nobody else was willing to publish them. Like Chip Delany’s Dhalgren, which was turned down by every publishing company in America.

TANGENT: How much can the editor of an anthology or a collection expect to get nowadays? As much as one of the contributors?

POHL: Usually the anthologist gets something like 40% of the income, which will be 40% of anything from $1,500 to anything you care to name. The average paperback anthology published by a major company should earn $3,000 or $4,000, so the anthologist should expect to get somewhere between $1,500 and $2,000 for himself.

TANGENT: Not to oversimplify matters, but say for example a reprint anthology: does the editor just choose the stories he wants to go into the collection and then try to sell the package to the publisher?

POHL: The hardest part is selling the idea to the publisher. Once you’ve done that, everything else comes easily, but every publisher, every company with a science fiction line, gets more proposals for a science fiction anthology than he can possibly use.

TANGENT: Would you relate how you went about setting up your own literary agency in 1939, turned it over to Doc Lowndes, and anything else you can recall of the experience?

POHL: I became an agent by persuading all the amateur writers I knew to give me their stories, and then submitting them. And most of them were amateur and weren’t very good and didn’t sell. I didn’t make a living out of being an agent, ever, until after the war. I tried it on and off before the war. To be an agent requires a great deal of work and is not nearly as much fun as writing. It requires almost the same skills as an editor or a writer, but it’s not as much fun.

TANGENT: Some agents seem to be very successful mainly because they’re extremely aggressive and hustle, hustle, hustle, to make a buck.

POHL: That’s one approach. Another approach is to find writers who you think deserve to be published and arrange to get them published, which is possibly something they couldn’t have done for themselves. Agents come in all shapes and sizes. There are buck hustlers and con men, and there are some that seriously take on the total lives of their clients, who don’t just try to sell them down the river for a fast commission but do what they think will help them grow as writers.

Why did I turn my agency over to Doc Lowndes? He was a friend of mine, I’d known him for a long time, and I couldn’t do it, I’d become an editor. Being an agent and being an editor are incompatible and I guess I thought it would be useful to him to have an opportunity to deal with editors, which it was because he got a job as an editor shortly after that.

TANGENT: What do you remember of the “exclusion act” imposed upon you and others at Nycon by the Moskowitz-Sykora-Taurasi axis, as briefly noted in Harry Warner, Jr’s. All Our Yesterdays? Could you fill in the details of that feud?

POHL: I’m writing my autobiography and I’m putting down everything I remember of it, and I’m having difficulty remembering much about it except that it happened. It was a long time ago, and I really didn’t care much one way or the other. The fun of it was in the feud itself, not in whether I got to the convention. We had our own counter-convention: Johnny Michel, Don Wollheim, Bob Lowndes, and a few other people and myself. We had most of the people who came from out of town to attend the New York convention at ours, too. So we really didn’t miss very much. I’ve never been much impressed by the program part of a convention anyway; it’s sitting around talking to people that’s fun.

POHL: I’m writing my autobiography and I’m putting down everything I remember of it, and I’m having difficulty remembering much about it except that it happened. It was a long time ago, and I really didn’t care much one way or the other. The fun of it was in the feud itself, not in whether I got to the convention. We had our own counter-convention: Johnny Michel, Don Wollheim, Bob Lowndes, and a few other people and myself. We had most of the people who came from out of town to attend the New York convention at ours, too. So we really didn’t miss very much. I’ve never been much impressed by the program part of a convention anyway; it’s sitting around talking to people that’s fun.

There was a feud going on between Wollheim, Lowndes, Michel, and myself on one side and Sykora, Taurasi, Moskowitz on the other, and they happened to win the power struggle at that point, and they got control of the convention – although it had been Wollheim’s idea in the first place.

TANGENT: You were first to receive a membership card and pay dues in FAPA (Fantasy Amateur Press Association) back in 1937. Are you still active in this longest running of the APAs? What do you remember of its beginnings?

POHL: No…(smiling) I haven’t been active in it since 1937. I was a member at first but I dropped out. It’s a way for amateur publishers who can’t command an audience any other way to make sure there’s somebody to read what they’re doing, and responds to it. It’s useful training and it’s a nice hobby and kind of fun, but I really don’t know anything about it except for the history. I’ve only seen an occasional copy of the magazines, and I don’t know how successful it is. I know for a long time it was a prestige thing to belong to–

TANGENT: I believe Harry Warner still belongs–

POHL: I wouldn’t be a bit surprised. Harry’s been around for a long time and he loves being a fan. He also wrote a few stories – one or two of which got published. (Chuckling) He’s much better at being a fan than he is at being a fiction writer.

TANGENT: You formed the Hydra Club in 1947 with Lester del Rey. Would you agree with Harry’s assessment of it as having a “stronger professional coloration” than other clubs of the time. What led you and Lester to form the Hydra Club?

POHL: What led Lester del Rey and me to form the Hydra Club was that after the war there was a convention in Philadelphia, and it was the first meeting I had had with science fiction people after the war, not having seen most of them for a long time, and we had such a hell of a good time that Lester and I decided to continue and recapture that pleasure by forming our own club. And it was primarily of people who had, or who intended to have, some professional connection with science fiction. But it wasn’t limited to them; there were a fair number of fans involved, too. It became more professional later on – more professional writers and editors and fewer fans, and so on – but we didn’t plan it that way, it just happened.

TANGENT: Many, many fans have gone on to become pros in the science fiction field. Is fandom still the largest breeding ground for future pros? Any personal thoughts?

POHL: There is no question that fandom is the breeding ground for future pros. There are very few successful professional science fiction writers who didn’t begin by reading it for fun, and then one day they say “Christ, I can do that well,” and they sit down and they try and some of them get published. Most people who read science fiction have some contact with fandom, especially when there’s so many conventions all over the place and they’re fairly well publicized. Most people who are deeply involved in science fiction at some time, either attend a convention or at least know people who do and know what it’s all about.

TANGENT: What major changes have you noticed in fandom over the years?

POHL: (Smiling) There’s a lot more girls in it than there used to be.

TANGENT: Did you ever have any acquaintance with Ray Palmer?

POHL: I don’t think I met him but once. Ray Palmer as an editor was highly successful in doing things I wouldn’t have touched with a ten-foot pole. But personally he was an immensely likeable guy. When I was a G.I. In World War II I came up to Chicago, and I didn’t have any money to speak of – I had lost it playing poker or something, but I didn’t have any – and I stopped in to see Ray, and he took the whole day to show me around Chicago. He was very kind to me, we’d never met before, he didn’t owe me a thing, but he was extremely nice and I’ve always appreciated that. And he has a reputation for being a decent human being to his writers and everybody else.

As an editor I think he was evil in some ways – the Shaver stuff was…immoral – but many other people have done things in order to sell a lot of magazines. He sold a lot of magazines. Amazing was never so healthy as when Ray was editor. I never read it, but… I didn’t like his writing very much, but there was no question that he had the key to the mint when he was editing Amazing. He knew exactly what his audience wanted and he gave it to them. It’s sort of what you were saying before – it’s all in how you define terms like good and bad. I think that what he did editorially was bad in that it was not anything like what I would do, but in terms of success, in terms of sales for the magazine, it was brilliant.

TANGENT: In the 1955 Galaxy novel contest you and Lester del Rey under the pseudonym of Edson McCann won first prize with Preferred Risk. Could you explain how and why you two got together on that? Was Horace Gold really hard-up for a good novel?

TANGENT: In the 1955 Galaxy novel contest you and Lester del Rey under the pseudonym of Edson McCann won first prize with Preferred Risk. Could you explain how and why you two got together on that? Was Horace Gold really hard-up for a good novel?

POHL: Horace Gold was extremely hard-up for a winning novel. He had a large number of selections. He had an apartment on East 14th Street and one room of it was wall-to-wall cardboard boxes containing novels. I helped Horace by reading manuscripts for him from time to time, and I read quite a few of them, so I know the ones I read were awful. For good reasons, that kind of contest never really works. I can explain theoretically why it does, but the observed fact is that it does not work. He asked me if I would let him publish a novel Cyril and I had written, Gladiator-at-Law, as the prize-winner, under a pen-name, and I said positively not. And he said, well, what am I going to do? I have to have a winning novel. And I said well let me talk to Lester, and I came back to Red Bank to talk to Lester – who had come to Red Bank to spend the weekend with us, but was still there eight months later. In fact, he bought a little house down the road from us and was there for about seventeen years – but we talked about it and we decided to write a novel…which, if I had written it or if Lester had written it, it would have been very good, but the two of us together did not function well. The chemistry was wrong. I hate the novel. He’s a much different kind of writer. He, at that time in particular, wrote in bursts and planned out what he was going to do ahead of time, and both of those are antipathetic to me.

TANGENT: What are your feelings on Horace Gold? Was he really too unscrupulous in his editing practices? Was he too restricting or controlling? How far, again, should an editor go in making unnotified changes?

POHL: I don’t think that Horace Gold was in any way unscrupulous in what he did. I think he was offensive and irritating and manic in what he did, but he didn’t do anything underhanded or morally wrong. He changed manuscripts a lot, but everybody knew he did it and those who didn’t want it done were perfectly free not to let him have their stories. He would change things around and never show the authors until they were in print, which was the custom at that time, and eveybody knew that he did that. It is no longer the custom. It is now the custom to ask the writers before making any significant changes. There too, it’s no moral question. It’s a matter of contract. The implicit contract with Horace was that he was going to edit something the way he felt like editing it. The implicit contract now is that editors will consult the writer about any significant changes, certainly. And now and then it’s made explicit.

In some book contracts, it is in the contract that the writer has the right of approval of the edited manuscript before it’s set in type. In practice, most writers have it with most book publishers because they get to see the galleys and make any changes they want to. They can change anything back the way they want it, if they don’t like the changes that have been made.

TANGENT: Do you care much if an editor wants to make some changes in your work?

POHL: Yes. In books I do, but in magazines I feel the editor has the right to do things the way he wants to. Sometimes I hate it, but it’s his ballpark and I let him play the game the way he wants to. But then again, I don’t write a great deal for magazines anymore.

TANGENT: Do you see a reversal of the “style over content” trend that so alarmed you in the early seventies?

POHL: I think that the trend has stopped. I don’t think there is a dichotomy between style and content anymore. At least not to the same extent. Some people are better at one thing than the other, and some are just the opposite. There’s still a lot of experimentation, but it seems to me to be more valid and more related to content. There’s an adage that says, “Style is the problem solved,” which is to say, the style you write something in should be the only possible style the story could be told in, and Joyce couldn’t have written Finnegan’s Wake any other way than that in which he did it. It happens to be incomprehensible to me, but that’s my lack, not the fault of the style.

The novel I have coming out from St. Martin’s Press, Gateway, is stylistically very flakey. The reason it’s the way it is, is that I don’t know any other way to tell that story.

TANGENT: It looks like you may have employed a Dos Passos technique of sorts.

POHL: Now Dos Passos used a running newspaper technique. This is something else. This is a total environment, not just dropping in bits from a newspaper. Brunner used the Dos Passos technique from the 1919 USA trilogy almost verbatim; mine is something different. I have data readouts, ads from newspapers, the personals, the songs, the letters that some of them have written, etc. The Sigfried von Shrink sections are all present tense, the remainder is all narrative historical past.

TANGENT: Have you read Joe Haldeman’s Mindbridge?

POHL: Yes, and when I started reading it I was worried, because I thought he was doing the same thing, but it turned out that what he was doing was something a little different. They’re both published by the same firm, by the way.

TANGENT: Knowing your likes and dislikes in the types of science fiction being written today – preferring the unmannered stylistic approach and good straight storytelling as opposed to an affected, mannered style which obfuscates instead of elucidates – why did you pick Dhalgren as one of your Fred Pohl Selections for Bantam Books? It seems the antithesis of all you favor in science fiction writing.

POHL: Well, you’re wrong in your premise. I’m not opposed to any particular style or any particular kind of writing. I’m only opposed to failures, not experiments that fail, and Dhalgren seemed to me to succeed. It was an experiment in describing a kind of environment that struck me as being exciting, interesting. I grant you there’s no plot, but I’m not so sure there’s no storyline; but nevertheless, Delany was showing a way for people to live, and people inhabiting this environment, that I liked. It touched something in me. To me it was an experience.

Now, you have to allow a writer his faults. I think that if Delany had been a different person I would have asked him to be allowed to cut 30% or maybe more out of Dhalgren. I think it would have improved it. But to Chip it’s not just a novel, it’s his life’s work. He spent something like six years writing it, and he’s still rewriting it.

TANGENT: Judy Lynn would probably say that just because it’s somebody’s life’s work, just because somebody sits down and types 80,000 or 100,000 words, that that is no justification for publishing it.

POHL: Judy Lynn turned it down, but that was before she realized it was going to sell more than half a million copies.

TANGENT: The primary reason I thought it incongruous of you to select Dhalgren – and this is where I got my original question about it – in the November, 1973 issue of The Alien Critic there is a reprint of a speech given by you at a con in London titled, “The Shape of Science Fiction to Come,” and you say the very things about style and storytelling I mentioned, and which you denied. Can you clear this up?

POHL: Well, I may well have said that. I do, in fact, believe it, but there is sort of a basic principle of editing, in addition to the one’s I mentioned before. If someone does something that you always knew was wrong, and nevertheless makes it work, that is not a reason for turning it down. That’s only a reason for changing your mind about what you thought was wrong. And Dhalgren seemed for me to work, in spite of the fact that it did a lot of things I’ve always felt to be wrong. It was much too long for what it had to say. It used that peculiarly offensive circular technique of ending the story at the beginning, and that’s childish stuff. Chip made it work. I have to say that theory falls before the fact – at least in this one case. Really, the thing that impresses me most about some writing is that it succeeds in the face of what I deem to be the right way to do something. Some of Sturgeon’s work is like that. Venus Plus X impressed me immensely when I read it, because although I admire Sturgeon’s writing and have always admired Sturgeon’s writing, I’ve always thought he had a lot of weaknesses. And Venus Plus X took all of his weaknesses and made a good novel out of them. I’ll have to say that there was something there that had previously escaped me.

TANGENT: Would you tell us your feelings when, in the 1950s, you helped Jack Williamson out of a writing slump? What were your feelings? How did this help you as a writer, if at all?

POHL: Well, I enjoy working with Jack Williamson largely because we’re so different. His attitudes and my attitudes are a lot different than each other’s. He and I disagree terribly on political questions, and lifestyle questions; he’s a very conservative southwestern-type person, and I’m not. We have great differences, and we have great differences in writing styles. I don’t write at all the way Jack does; our stories don’t look alike. When we work together we get something that is quite different. When Cyril and I worked together, really either one of us could have written the same story. When Jack and I work together we get something neither one of us could have written. That doesn’t mean that it’s necessarily better or worse, it’s just different. It’s a change from what I’ve been doing. I admire his ability to create colorful backgrounds and organisms and semi-scientific technological things, because it creates a lot of color, excitement and adventure.

Someone asked me once why I liked some things that were not a bit like some things I wrote. The answer is that there are some things I like that I don’t know how to write. One of them is the colorful space adventure that Jack Williamson does. Working with him gives me an opportunity to do it, leaning on him. And there are things about Jack’s writing that I do better. So the two of us…(smiling)…well, Jack’s all wet on politics, and he’s all wet on lifestyles.

TANGENT: Be careful now, if he does the introduction to this interview he’ll have the last word on you.

POHL: That’s alright. Jack knows what I mean. Jack is a very good friend of mine, and he knows it. He knows we differ on some questions. Jack deserves the last word.

TANGENT: Why do you believe the editing of collections to be too easy, and is this really why you quit doing them? You and Carol do an occasional anthology/collection featuring newer talent.

POHL: I quit doing them as a matter of routine because they’re not very challenging. There’s nothing to do in an anthology or a collection that I hadn’t already done. I did do a couple of collections with Carol because there were a couple of books I wanted to do, and it seemed convenient to do them with her. And then Bantam asked me to do an anthology and I said I would if I could do it with Carol, because I wanted to get another point of view on the stories. I didn’t want to edit a science fiction anthology just for science fiction specialists. Carol’s been exposed to science fiction for a long time but she doesn’t really read a great deal of it. She knows about as many of the science fiction writers as I do, but because she has not been exposed to science fiction in great volume all her life she has a better way of judging what will appeal to people who are not specialists than I do. I have to do it with artisanry and she can do it instinctively. And we may do another Science Fiction Discovery, the first one seems to be going well.

TANGENT: Concerning your novel Man Plus: It seemed to me that the book ended much too quickly, and although you did a remarkable job on the psychology of Roger Torroway during his transition from a man to a cyborg, there really didn’t seem to be much need for him on Mars. What could you say about this?

TANGENT: Concerning your novel Man Plus: It seemed to me that the book ended much too quickly, and although you did a remarkable job on the psychology of Roger Torroway during his transition from a man to a cyborg, there really didn’t seem to be much need for him on Mars. What could you say about this?

POHL: I could say that you are right, which is true. I could also say that the point of the novel was that there was no particular need for him on Mars, and that if the computer intelligence had had a reason for him to be on Mars they wouldn’t have had to fake up the public opinion polls, and so on. The reason he was there was because they wanted him there, not because he served any function for the human race there. In literary terms, in artistic terms, you’re right; it was disappointing that he really had nothing to do once on Mars, but the fact that I can justify it doesn’t mean that I can defend it.

TANGENT: All of Torroway’s actions, everything he saw, heard, felt, etc. was so consistent, reliable, within the parameters imposed on, or granted him, by his position as a cyborg. How could you render his changed perceptions of the outside world so accurate and consistent while doing no real research?

POHL: The reason that it’s possible to be consistent and fairly reliable without doing research is that I take so bloody long to write a book. Man Plus stems from something I began writing in 1966. What I do, with most novels and generally with everything, is to write little bits of it as long as I know what I’m doing and then put it aside for a little while and work on something else and then go back and look at it again, and if there’s something wrong I can usually see it after a lapse of time. So if there’s an inconsistency or blunder or something else that doesn’t seem to be working I can usually tell. Time gives it an opportunity to cool off and I can look at it more objectively, like a critic rather than in the heat of creation. And I recommend that to any writer; do as much as you can while you know what you’re doing, and when you find yourself beginning to flounder stop and do something else for awhile, and take some time before you look at it again.

TANGENT: What did you set out to do in Man Plus? What was your ultimate aim, or goal?

POHL: I don’t have goals in books; I don’t like to think in terms of what the total effect of the book is going to be when I write it. With almost all books, stories, articles, anything, I start with a question in my mind and explore it as I go along. What would it be like to be a cyborg? And I try to figure it out as I go along; the advantages, the disadvantages, what would it feel like, what would happen, why would anybody have a cyborg, why would you, as the main character, be the one who was selected, and so forth. I start wondering and try to supply answers, and the answers become the plot. This isn’t always true, but nothing is always true, but this is a good approximate description of what I mostly do.

TANGENT: When Ben Bova visited Oshkosh last year he talked about the Viking landings on Mars. During the talk he threw out an argument which says that if we could afford it, the easiest way to find out about Mars would be to just send a man there instead of having to pay for and design all sorts of devices. And of course that’s what you’ve done in Man Plus. Do you think turning a man into a cyborg – to be used only once on the surface of Mars as Torroway was supposed to be used – will be any cheaper to design than say, for instance, the $5,000,000 brain box that went up with the Viking Project?

POHL: I’m familiar with that argument. No, I think that Ben’s wrong about that. The manned space program is a considerable waste of money if you view the space program as a mechanism for answering questions. If the question you want answered is What is Mars like?, it’s cheaper and a lot more effective to send a lot of smaller, and less complex devices. The support systems for a man on Mars would be immense. It’s not just a matter of sending three people to the moon with a total trip time of twelve days or something. It’s a matter of something like three or four years of having food and air and whatever medical stuff is needed, and water, for one man, and I don’t think at present we can build a spaceship that would be able to do it. I could predict when we might be able to do it, but there’s no such thing as predicting what’s going to happen, in that sense. I can’t say when we’d be able to build a spaceship. But I can say that it could be done in five or ten years from now, if someone wanted to do it, if someone like Jimmy Carter wanted to do it, if someone were capable of mobilizing the capital and so on, decided to make it happen it would happen. But as things now appear, it’s not going to happen in 2026 or any other time until some other conditions change.

TANGENT: Do you think that subconsciously maybe the argument about sending a man to Mars being cheaper, etc. may have been an influence on your writing Man Plus?

POHL: Not really. No, I think that all of Man Plus stems from the suggestion that was made to me by a movie producer in 1966, that I think about a story involving a cyborg going to Mars, and my wondering what it would be like and trying to find out answers. There was no normative purpose involved, I wasn’t trying to make it go any particular way, I wasn’t trying to prove a point or to convince anybody of anything. I was just trying to answer in my own mind, and on paper for readers, what I thought likely to be the feelings and experiences of a cyborg going to Mars.

TANGENT: At the end of the book it is revealed that it has been the computer intelligence that has been telling the story, it is they who are the “we” in the narration. I was surprised that I hadn’t figured that out earlier on in the book. Was it that obvious, do you think, and am I just slow, or what?

POHL: It’s surprising to me that the people who haven’t read much science fiction figure out that it’s the computers before the science fiction fans do. A couple of people I know who have read it, have never read any other science fiction, figured out that the voice who was saying “we” now and then, had to be the world network of computers. I think it’s a matter of your anticipations. I think science fiction readers are anticipating a different order of things than the people who aren’t.

TANGENT: You’ve said you think Gateway is your best book. Why? What is so different about Gateway?

TANGENT: You’ve said you think Gateway is your best book. Why? What is so different about Gateway?

POHL: It’s my Dhalgren. I don’t think anybody else in the world could have written it. A lot of people might have been able to write Man Plus, or something very close to it. There are a lot of stories about cyborgs. There are elements of Man Plus that I don’t think most people would be likely to include, but they are available from the public domain. The stuff about mediation of sensory inputs and so on you could find if you wanted to look for it. But Gateway is conceptually mine, and stylistically mine, and it’s got a lot of personal feelings and attitudes in it that are mine. They belong to me. It’s of my flesh; if it’s cut I bleed. I really don’t think anyone else could have written it. It was all hard, it was very hard. I wrote it in a very unusual way for me. I usually start on page one and go to page three hundred, or whatever, over a long period of time, consecutively. But Gateway was not written consecutively; I wrote chunks of it. I went on a cruise in the Fall of 1974 and I took the fragmentary manuscript with me, and I had pieces of it scattered all over my stateroom trying to put them in order. And I couldn’t. It took forever to juggle it into the proper running order, but finally I got it into what seemed to me to be the proper running order. And then there was a lot of rewriting, addition, and changing and so forth.

TANGENT: Were the changes of your own volition or a publisher’s?

POHL: My own volition. I don’t let publishers tell me what to do. I have a built-in safety device that most writers don’t; if any other editor gives me trouble with a manuscript I’ll publish it myself.

TANGENT: Did you have any problems of this nature working with Horace Gold?

POHL: Horace and I had many, many tiffs. We had endless arguments. That was one of the things I liked about working with Horace.

Back to your original question about Gateway. Really, I’m a little reluctant to talk about it at all except about questions about what I did, the chronology of it and so on. I don’t like talking about the implications of it or the meaning of it or anything like that. If it doesn’t speak for itself then there’s no reason my speaking for it.

TANGENT: What is it in science fiction that really raises your hackles? The writing, the fans, publishers, editors? What?

POHL: I think there’s a great deal of lousy science fiction being published, and it’s not entirely the fault of the editors or the writers. I’m not sure whose fault it is, but it bothers me to see some bad books being published when there’s no excuse for them. It’s a matter of the dynamics of the system we live under. There are lines of science fiction books – which I will not name, but you could probably figure out what they are if you wanted to – which are edited by people who don’t know what they are doing. They’re written to the specifications of people who don’t know what they’re doing, and they’re awful. And I resent the fact that these people are “fouling the well I drink from,” but I don’t resent it enough to really worry about it a lot because readers are fairly selective. They may not be consciously aware that X book is bad because it’s a part of Y line, and edited by Z who’s an idiot, but sooner or later they find there are some things they like and some things they don’t, and ultimately, I think, virtue prevails. I think good books do better than bad books, by and large. I think this is true even in the case of big runaway bestsellers that are obviously trash but which sell six million copies. They may sell six million copies today, but five years from now nobody will have remembered them. There are science fiction books that are still living after seventy-five years or more. A lot of the science fiction stays alive, ten, twenty, thirty years.

TANGENT: What do you think of science fiction expanding into all of the different media? We have the records, tapes, comic books, television, etc. plus the books.

POHL: I think that the other media are peripheral. I get involved in them from time to time. I’m making a record and I have a contract to do the pilot script – and the treatment – for a new television series. It’s called “The Clone Master” at the moment. It’s not an anthology series, it’s a series series. They trapped me into it by promising me that it would be an anthology series. Now, this is one that I generated. The producer asked me for some suggestions and I told him that it should be an anthology series and ultimately badgered me down to where I am now. The process is one of badgering down. You get into television and you find there are twenty-five people who are being paid to criticize what you do and they all have to justify their salaries. It’s no fun, I don’t like doing it. I do like it in the sense that I like experimenting on my own in areas that I haven’t done before.

TANGENT: Do you find that more difficult than what you’ve done before?

POHL: It’s both. It’s more difficult in that I have all these external forces that I’m not used to. There are twenty-five network, and agency, and producer people who feel obliged to get into the act.

TANGENT: Do you think you can appreciate what some of Harlan Ellison’s troubles have been like?

POHL: Nobody makes Harlan do that. There’s no contract signed in heaven that binds him to write for television. He does it because he wants to. We had a big argument about that at a con last Fall. I told him that he should quit bitching; if he took the money, then he should do it. If he didn’t want to do it all he had to do was give up the money. And he said Yes, well, that’s what makes it possible for me to write science fiction. Which…(smiling)…is also arguable.

TANGENT: By what process do you select the books for your Fred Pohl Selections for Bantam? Do you solicit or just choose from among those you happen to receive in the mail? They don’t seem to appear with much regularity, or in much number.

POHL: No. It’s very complicated and I despair about telling you about it on one cassette. Basically, Bantam publishes about twenty-five books a month, above the line, as it’s called; the principle list has about twenty-five titles a month. And the competition to get one’s books into those twenty-five slots is immense. There are a lot of books and a lot of editors at Bantam, and quite a few of the books never get published because they never find a place to publish them. So, I have to fight for space to get my books out, and since I’m only in the office one day a week there are four days and one morning when somebody can steal my space away from me. I do have a lot of cooperation with Bantam. Bantam is very good about dealing with me; they are very considerate and thoughtful and rewarding, but I really don’t enjoy editing paperbound books the same way that I did editing a magazine.

TANGENT: Because of the difference in audience?

POHL: No, the audience is probably very similar. The environment is different. It’s not a one-man show. I’m used to doing everything myself, and Bantam has specialists in everything, and it involves more teamwork than I like. I’m not a team player. I’m perfectly willing to do what someone else wants if I find myself in a position where… Oh, I don’t know. I’m a trustee at a school for handicapped kids; I’ve been a trustee at my local church, and if I’m put on a job and someone else is in charge of it then I’d try to do what he says, but I’m not willing to spend most of my effort in discussing what should be done. I want someone to make decisions, and in teamwork there is much more time in discussing than in doing.

TANGENT: In The Age of the Pussyfoot you delve into some of the ramifications of cryogenics. The legal, moral, individual problems, and so on. I find cryogenics truly fascinating and would like to ask you if you, personally, had a chance to be frozen and then revived in the future, would you take that opportunity?

TANGENT: In The Age of the Pussyfoot you delve into some of the ramifications of cryogenics. The legal, moral, individual problems, and so on. I find cryogenics truly fascinating and would like to ask you if you, personally, had a chance to be frozen and then revived in the future, would you take that opportunity?

POHL: I may be vain enough but I’m not motivated enough. The things that make me want to keep on living, and I think they’re probably true for most people, are the network of associations and relationships and projects, and so on, that I’m involved in. If I were to be frozen for five hundred years and thawed out in an environment where I didn’t know anybody, and didn’t have any particular function, it might be interesting in the sense that Easter Island would be interesting. It would only be that, an excursion, and not a continuation of the life I now have. I’m not that highly motivated. If you want to be frozen and revived you’ve got to make considerable sacrifices here and now, and I don’t care that much. I’m not at all, consciously, afraid of dying. I expect it to happen some time or other and it doesn’t bother me. Of course, possibly, on my death bed things will seem different.

Frederik Pohl interview copyright © 1977, 2013 Dave Truesdale.

All Rights Reserved.