Reviewed by John Sulyok

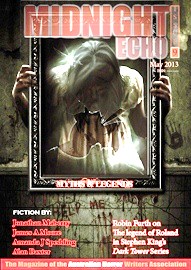

Midnight Echo is the official magazine of the Australian Horror Writers Association and is published each May and November. It is available in both print and electronic formats. Edited by Geoff Brown, this issue features more than 100 pages of fiction, art, interviews, book releases, and more.

“Black Peter” by Martin Livings

“Black Peter” is a premise without a plot. It doesn’t set a destination nor does it go anywhere. The story follows Black Peter, quite literally, as he wanders through a French town, angry at everyone around him. He is belligerent and rude; the protagonist for sure, but nowhere near a hero. He enters the Basilica de San Nicola, and we begin to see where this is going. Taking a small French boy by the arm, he leads him into a crypt—passing directly through the locked wooden door. It is inside the vault that another is there to confront Black Peter.

The conclusion relies on the all-too-common trope of revelation. Rather than setting up a confrontation and having the characters go through change, information is withheld from the audience only to be revealed at the end, garnering an “Ah. I see.” reaction. Stories as short as “Black Peter” should hit the reader hard and when they’re not expecting it, or leave the reader with something to think about. This story does neither.

“Black Train Blues” by James A. Moore

Bram Whittaker has a problem. People working on his railroad are dying, and sightings of a ghost train are being reported. Bram has the local telegrapher send messages to a number of towns, in the hopes of finding the one man Bram thinks can help: Jonathan Crowley. As luck would have it, Crowley gets Bram’s message and shows up with a pale man named Slate. Crowley and Slate are a mysterious pair, weathered by past experiences and focused on helping those in need. The case is right up their alley, but even if Crowley can come up with answers, will Bram be able to accept them?

“Black Train Blues” feels like The Further Adventures of Crowley and Slate. That is to say, it feels like the characters have history and a future, and that they fit into (the shadows of) their Wild West world. The reader will want more of these characters, more adventures, more sinister mysteries. If there is anything to say against James A. Moore’s tale, it’s that it is often overly described. Too much time is spent on unimportant details, where that time could have been better spent with the characters. The great westerns are sparse in their storytelling, leaving the characters to fill in the gaps with their attitudes and actions. Wanting more time with Crowley and Slate, however, is only a compliment.

“Little Boy, Little Girl, Lost in the Woods” by Mark Patrick Lynch

“That which you want will cost you most dear.” So were the words of the witch to the husband and wife who could not have children on their own. Her spells cast, the couple made good. Or at least, they became pregnant. What came from that pregnancy was altogether not good. The mother died during childbirth, the father wished he had never been able to sow their seed in the first place. Hans and Greta, however, were born, and their father couldn’t have been more horrified of his offspring.

Mark Patrick Lynch reimagines the tale of Hansel and Gretal, recasting characters and moving the narrative to their father. The children in this version are the villains, the witch sought after. It’s a harrowing tale that is written to embody the feel of folklore, but without the stilted prose and dialogue that so often mars the reading experience.

“Coffee Rings” by Kristin Dearborn

She believes in them. She reads about them and studies about them. She wants nothing more than to be like them. Be with them. Because they’ll understand her like no one else does, because she understands them like no one else does. But when she and her friend finally meet them, they are not what she had imagined. They kill her friend. Eventually they make her kill too, to protect herself… Or so she thinks. The worst part, really, is that she can’t drink coffee for fear of leaving them rings through which to get to her. For all the love she once had for them, she now lives in fear of the faeries.

Who says that faeries are always good? Not Kristin Dearborn. Instead, “Coffee Rings” twists the expected and delivers a good little read about a girl and her obsessions.

“The Wee Folk” by JG Faherty

Kip and Elise have powers. She can know truths, he can see through the eyes of others when touching their bones. And they both know about the wee folk and the treaty between their worlds. Oh, and Kip’s great-great-grandmother was also able to control the wee folk. So when a murder arises, Sheriff Roy Coombs comes to the couple for answers.

“The Wee Folk” is too short and hollow to be recommended at all. It seems to rely on a twist/reveal ending, but it never comes. The climax is barren of reason or excitement, and the events leading to it are weightless.

“The Road” by Amanda J. Spedding

“The Road” is equivalent to a mindless action movie. It’s one horrific encounter after another for Riley, a woman or girl (it’s never made clear), as she walks along the road. What the road is, why she is on it, where she came from, or what the horrors are is left frustratingly ambiguous. The reader doesn’t know the why, only the what, and even that is often a confusing mess. And each successive encounter becomes less and less horrifying, because it becomes expected. For something to be frightening, disturbing, or unsettling it has to be the exception, not the norm. After half a dozen encounters, it’s a relief to see Riley’s tale come to an end, whatever the point of it was.

“The Fathomed Wreck to See” by Alan Baxter

Dylan slapped his wife across her cheek, leaving it red, leaving him ashamed. Why had he done that? Perhaps because the pain and the separation would be less of a burden on her than knowing the truth. That he is dying. Perhaps the truth is too much for himself as well. Dylan takes refuge in his boat at the marina, taking to the dark waters in the evening, looking for solitude. Finding anything but. What is it that calls to him, that sings to him from the waters deep? Questions and answers.

“The Fathomed Wreck to See” is told in a gentle, rolling prose that moves events along in a steady, well-paced rhythm. Dylan’s problems compound each other, turning his life into a house of cards on the verge of collapse. And now and then, forceful waves crash against the shore of his perception, catching him off guard, leaving the reader curious for his reaction.

“Changeling” by Jonathan Maberry

Joe Ledger is an agent with the Department of Military Sciences (DMS), which grants him unparalleled access, which in the case of “Changeling” are the Koenig labs. Scientists have gone missing, the labs have been vacated, and word has come down that genetically malleable super soldiers are being developed. But when Joe investigates, he’s confronted by more than an empty lab. Another agent appears, quite literally, and makes Joe question his sanity, because she’s supposed to be dead.

“Changeling” is familiar. It reads like any crime/mystery series with a likable protagonist, free-flowing prose, humor-infused banter, and a colourful cast of supporting characters. That said, it’s an entertaining page-turner, and may make you want to pick up other Joe Ledger novels.