Sci Phi Journal, 2025/4

Sci Phi Journal, 2025/4

“What Happened At Delphi?” by Richard Lau

“Impossible Things Scavenger Hunt” by Jeff Currier

“New France’s Finest Hour” by Matias Travieso-Diaz

“The Ones Who Walk Away From New Jerusalem” by Andy Dibble

“The Inferno Of Boniface VIII” by Joachim Glage

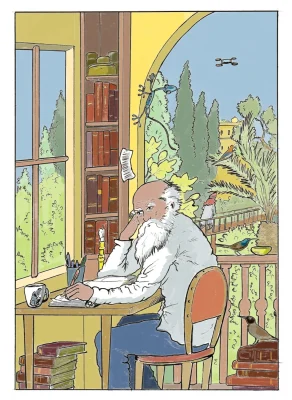

“Bentham In Heaven” by Alexander B. Joy

“Psychopompeii” by George Salis

“An Object Of Confined Infinity” by Robert L. Jones III

“The Last Page Of The Magazine” by Andrew Gudgel

Reviewed by Axylus

The nine tales in this issue are sequels of stories from past issues of Sci Phi Journal.

In “What Happened At Delphi?” by Richard Lau, Prometheus once again gives humanity a gift, this time the power of dark energy. Zeus cannot accept the possibility that humans will benefit. After consulting with a wise elder god named Schrodingememnon, Zeus gives Pandora yet another box, this one containing a fateful degree of uncertainty. Mapping cornerstones of quantum theory onto Greek mythology is a clever idea, but this story serves more as entertainment than illustration.

“Impossible Things Scavenger Hunt” by Jeff Currier describes a game that two interlocutors play as they discuss different events or objects that are somehow impossible (or impermissible, in one case) More later on this story. Another story in this issue is “Bentham In Heaven” by Alexander B. Joy, which finds Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill in a heaven or utopia as it would exist in a reductio ad absurdum extension of Bentham’s Utilitarian philosophy. [It’s actually a bit of a straw man, since Bentham’s thought was more complicated than is presented, and had more to do with morality and good governance than utopia. And JSM even fell into depression due to a fearful belief that a utopia similar to the one in this anecdote could never bring him happiness.] But never mind all that—since we already have games on one hand and utopia on the other, why not do a mashup with The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia by Bernard Suits? In that work, which is important in the philosophy of sports, Suits has the Grasshopper argue that if utopia did exist, everyone in its domain would spend their time playing games. So throw all these characters in together in a philosophical tag team wrestling match. Knowing Mill was a pushover for the wares of the Romantic poets, Currier’s protagonists would sneak Friedrich Schiller and William Wordsworth in as ringers. Schiller could unleash an opening salvo of Romanticism into the face of JSM: “Freude, schöner Götterfunken… Wer ein holdes Weib errungen, Mische seinen Jubel ein!” [Joy, bright spark of divinity… whoever has won a true and loving wife, join in his jubilation!] JSM would collapse in a pitiful heap and throw in the towel, remembering his beloved Harriet Taylor. Then Wordsworth, tagged in by Schiller, would deliver the coup de grâce from his “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.” Its pangs of nostalgia, intertwined with strands of inner joy and pain, would send our poor Jeremy Bentham into blubbering tears, remembering the bliss of his youthful days at Bowood House. Team Utilitarianism would lose in a rout. More seriously, the omission of facets of human existence that these philosophers valued so greatly in their personal lives is a weakness in the (admittedly, tongue in cheek) argument being presented. In the end, the Grasshopper would award victory to the two protagonists of “Impossible Things Scavenger Hunt,” simply because they were the ones wise enough to spend their time playing games in the first place. “Impossible Things Scavenger Hunt” by Jeff Currier might appeal to readers who enjoy fiddling with clever concepts. “Bentham In Heaven” by Alexander B. Joy is mildly amusing despite its shortcomings. However, utilitarianism has already been very effectively savaged within the realm of fiction by “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” by Ursula K. Le Guin, which will feature in a later review.

“New France’s Finest Hour” by Matias Travieso-Diaz, spends about 1900 words on three alternate history anecdotes which assume that the Spanish Armada defeated England in 1588, and North America has been under the control of the crown of France. It is an interesting example of worldbuilding, but lacks any substantial storytelling.

“The Ones Who Walk Away From New Jerusalem” by Andy Dibble is billed as a spiritual sequel to Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” It depicts a celebration in heaven at the expected return of Christ, but Christ does not show up for the party. Nevertheless, joy continues in heaven unabated; its dwellers are unperturbed. Dibble’s anecdote continually breaks the Fourth Wall in small asides implying that all our perceptions of heaven, and presumably therefore of God, are limited by our various restrictive biases, and our attempts to stuff the Creator into any single definitive box. It later describes Christ as being present in the New Jerusalem, but hidden away in the Temple, where no one looks at him. In his hidden chamber, he is not one person or entity, but multiple co-existing instantiations of himself that encapsulate various points in the chronology of his life, from childhood to crucifixion. Each Christ has his own goals and concerns apart from the others, rather than one single identity and purpose: “Behold the man, all of him. Many in one, crucified and rising again, a web of men and boys locked in bloody melee, a gory shudder.” This again tosses aside any orthodox understanding of Christ. The point of intersection between this tale and Le Guin’s famous story is that if these Christs emerge from the Temple, then the joy of the New Jerusalem will fall and all will be destroyed. Dibble goes on to suggest that Christ did not truly consent to his own crucifixion. Moreover, Satan’s refusal to bow to Adam (which is never mentioned in the Bible) was not born of sinful pride, but sprang from a pure and true allegiance to God: “They say he refused to bow down before any but God, though it might mean eternal separation from his beloved.” As its pièce de résistance, this piece suggests that those among humankind who turn away from any orthodox understanding of God, Christian doctrine, and Christian heaven are the ones who are truly righteous. They are “..these who love Christ too well to obey him,” driven by integrity to emulate the admirable fallen angel Satan. Le Guin’s Omelas knocked the legs out from under utilitarianism; this evocative anecdote labors to do the same for any understanding of God based on orthodox Christianity. It will resonate with readers who are convinced that the specific details and doctrines of Christianity are at best a sham, but who still believe or hope there may be a deeper truth recoverable somewhere within a nonspecific form of spirituality that has lost its orthodox shackles. For my taste, however, this tale is a shade too pleased with itself and (perhaps ironically) a little too preachy.

“The Inferno Of Boniface VIII” is a short story by Joachim Glage. In his dreams, Pope Boniface VIII regularly experiences the physical tortures that he is depicted as suffering in Dante’s Inferno. On the very last night of his life, however, he meets the real Satan, who tells him that his fate is worse than anything in Dante’s hell. As nearly as I can determine, the true nature of hell which Boniface must face is an eternity of being unable to lie to himself, unable to hide from or evade the truth about himself, and perpetually confronted with that truth, without relief. That does sound kinda hellish, when you think about it.

“Psychopompeii” by George Salis draws its title of course from a portmanteau of “psychopomp” and “Pompeii.” It deals with the land of the dead, or the creation of a new one, as the citizens of Pompeii gawk at the inferno of Vesuvius and are transformed into a new and perhaps tortured form of life.

Clocking in at just over 300 words, “An Object Of Confined Infinity” by Robert L. Jones III describes a mysterious artifact that reifies the nature of the irrational number pi (π).

I am neither a philosopher nor a scientist. My PhD is in English. “The Last Page Of The Magazine” by Andrew Gudgel is the only entry in this issue which I firmly enjoyed, though my background probably colored my conclusions. The spare prose of Gudgel’s piece was touching and its central concept (as far as I am aware) original. Framed as an obituary, it describes a species of non-communicative and rather cute interstellar visitors called the Aydax who had arrived on Earth 89 years ago, in the year 2039. The overwhelming majority rocketed back into space in 2103, leaving behind a small number of stragglers. The very last of these to die, “Stumpy,” passes away in 2128, having never made any perceptible attempt to communicate. From my perspective, this one is recommended. Moreover, I clicked back to the tale that this one serves as a sequel for: “Social Aspects Of The Aydax Phenomenon: A Literature Review,” published in Sci Phi Journal in 2021. I liked that one, too.