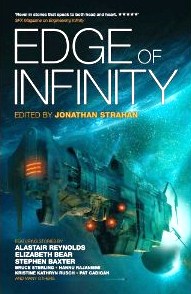

ed. by Jonathan Strahan

(Solaris, November 2012)

Reviewed by Robert E. Waters

Thirteen stories are contained in this anthology, a continuation of Strahan’s “Infinity” series, which began with Solaris’ Engineering Infinity. The theme of this particular volume is the spread of man throughout our own solar system, and what that means in terms of our continued existence as a viable species. Big ideas have almost always been the bedrock of most of Strahan’s anthologies. This one is no exception.

Pat Cadigan starts us off with “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out for Sushi.” Written in Cadigan’s patented witty, fast-paced manner, it tells the story of Fry, a human “two-stepper” (cause she’s only got two legs) who comes out to the Jovian planets to work with a group of genetically transformed humans known as “sushi.” These extremophiles take on aquatic forms – octopi, crabs, chambered nautiluses, etc. – due to Jupiter’s and Saturn’s harsh climates, intense pressures, and the constant zero gravity. In these new post-human forms, people can simply live better and longer lives beyond the asteroid belt. After an accident, Fry decides to shrug off the old skeleton to become one of them, and so the story basically revolves around her transformation… with a dash of interstellar politics thrown in for good measure. As you might infer, it’s quite funny on one level, with characters named Fry, Aunt Chovie, Splat, and Bait. On another level, it’s quite creepy. The nonchalant, matter-of-fact manner in which these transformed humans view themselves seems even more “alien” to my mind than a real alien species would. But that’s what made it fun to read.

“The Deeps of the Sky” by Elizabeth Bear is about an atmosphere miner named Stormchases. He flies through intense storms gathering gasses, minerals, and organic compounds. He does this to create a dowry or treasure chest of goodies so that he may be more appealing to a Drift-World, or a so-called “Mothergrave” that he’s been trying to impress for some time. Once a Mothergrave accepts him, he can then join with her to create a life-long symbiotic relationship. This is all very fun and interesting speculation to read about. Where I had a problem, however, was trying to understand exactly where this story was set. Was it on Jupiter? The descriptions of the massive storms seem to suggest so, but it’s never clearly stated. Later on, Stormchases has a meeting with an “alien” visitor (a human) and they make interesting conversation. But are Stormchases and his Mothergrave true aliens themselves, or are they transplanted humans that have evolved so far beyond their humanness as to not recognize it anymore? As a reader, I would accept either answer, but I was left not knowing for sure.

James S.A. Corey’s “Drive” is set in Corey’s Expanse universe (Corey is the pseudonym of Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck), one of the more popular space opera series on the market today (with titles such as Leviathan Wakes, Calaban’s War, etc.). It’s about Solomon, a Martian who meets a lunar girl named Caitlin, visiting the Red Planet on business. They talk, they fall in love, and eventually marry. Interwoven through this rather pleasant, though mundane, relationship, is Solomon on a flight in a ship at break-neck speed. What’s he doing and why’s he doing it? In time, we learn that he is testing a new interstellar drive that he hopes will allow Mars to become a powerful, independent entity beyond the asteroid belt, no longer living under Earth’s boot heal. Does he succeed? I won’t tell you, but I did like the story. Also, although Solomon’s relationship with Caitlin was a bit ho-hum, I found that part to be the most interesting. Testing the “drive” mattered of course, but it was more of a means to an ends than the critical part. The best stories are about relationships. Solomon and Caitlin are by no means Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennett, but they’ll do.

“The Road to NPS” by Sandra McDonald and Stephen D. Covey is set on Europa. Rahiti Ochoa, aka the Crazy Samoan, has won a contract to try to transport goods from outpost to outpost across the frigid, frozen surface of the moon. The traditional way is through a very costly drop system. If he can prove that moving materials via sled is cheaper, he’ll become rich beyond his wildest dreams… or at least rich enough to book passage back to Earth. I’d take that action any day myself, and Ochoa is certainly up for the challenge. Along the way, he and his companion encounter all kinds of hazards, and even have a face-to-face with some of the indigenous life. Not a bad story; a reasonably solid adventure, but not anything spellbinding either.

I found John Barnes’ “Swift as a Dream and Fleeting as a Sigh” a little difficult to parse at first. Here, we have two humans, Laura and Tyward, getting couples’ counseling from a so-called AHAI, an artificial intelligence with cognitive speeds that make it think a human second is like an hour. We also have a robotic ant-like device that mines coal which is then used to propel spacecraft up to light speed. These ant creatures are intelligent enough to figure out ways to manipulate the emotions of their masters. In this case, it’s Tyward who’s a sensitive lad who does not like being insulted by his creations. Laura is concerned with Tyward’s lack of manliness, it would seem, and so it’s AHAI to the rescue. Along the way, you get the impression that it and other councilors are in control of the human race. Then, there’s a switcheroo at the end that is interesting, but as I say, the details beforehand took a little too long for me to figure out.

“Macy Minot’s Last Christmas on Dione, Ring Racing, Fiddler’s Green, the Potter’s Garden” by Paul McAuley is as big and majestic as the title suggests. Set in the author’s Quiet War milieu, it tells of Mai’s journey to the Saturn moon Dione, where her estranged father has passed away. She is going there to participate in the spreading of his ashes, and to figure out who this person was that she had not seen and spoken to in over a decade. The essence of the story can be summed up by McAuley’s own words:

“When your parents die, you finally take full possession of your life, and wonder how much of it has been shaped by conscience decision, and how much by inheritance in all its forms.”

That’s what this story is about, interwoven through a panoply of music and artistic forms that have been created by the Dioneans through beautiful life-sized ice sculptures that pepper the moon’s harsh landscape to give it a human touch. Along the way, we are told stories about so-called “outers” who have participated in races around the rings of Saturn, living in planetoids among the outer planets, and even habitats that touch the very edges of the Kuiper Belt. Some might consider these pauses in the main storyline distractions, but that is untrue. It is necessary for Mai to hear these stories, experience them from the Dioneans’ own words to understand the world that her father had chosen to live and to die in. McAuley’s story is one of those jewels of speculation that reminds us all why we love science fiction.

Kristine Kathryn Rusch has one of the most pleasant and easily readable styles in the sf field today. “Safety Tests” is no exception, as we meet Devlin, a bored spacecraft certification instructor at the License and Regulation (L&R) facility. Those needing flight permits for whatever reason come to good ol’ Devlin, and he’s just the man to find any excuse to fail them. Between you and me, I found Dev to be a snarky little pain in the ass, one of those middle-rung types so bored with his own existence that he barely acknowledges the humanity around him. And of course, that’s the point Rusch is trying to make: the more things change, the more they stay the same. The DMV in space. There isn’t much else to this story; it’s a day in the life of a bureaucrat – with a little tension and danger thrown in for spice – but it’s a fun, quick read.

“Bricks, Sticks, Straw” by Gwyneth Jones is a great idea that suffers from structural problems. Here we have a young science team working from Earth, projecting themselves through outer solar system remotes currently deployed to various moons of Jupiter to monitor and collect data on the big daddy. When a nasty solar storm knocks out most of Earth’s electronics, these semi-intelligent robots (the virtual scientists) find themselves stuck without communication to the home base. Thus, they have to try to survive within these machines, all the while fearing death through data rot and delirium. I think this premise is very clever. The problem, however, is that it took about half the story for the author to slow down long enough to explain what was going on. Until then, I was totally lost, and wanted to stop.

I consider myself a pretty sophisticated reader, and I’ve been reviewing short fiction for Tangent for quite some time. However, I have to say right up front that Hannu Rajaniemi’s “Tyche and the Ants” escaped me. Tyche lives on the moon in a dream-like protective custody under a so-called Brain, which I gather is a virtual, computerized presence. Apparently, Tyche is a “Grey,” which I first assumed was one of those classic oval-eyed aliens we read so much about in the tabloids, but then I got the impression that the Greys of this story were genetically-manufactured other beings that Earthlings grew jealous and fearful of and forced them to fleet to space. Maybe they’re both. Eventually, Earth gets wise to Tyche’s presence and sends ruffians (the ants) to root her out, thus forcing her and the Brain to flee. Interwoven into all this is (I assume) Chinese culture and mythology (although I could be dead wrong since I’m no expert). We have a Secret Door, a Great Wrong Place, a Chang’e the Moon Girl, an Other Moon, a Big Old One and a Troll, a General Nutsy Nutsy, a Mr Cute… ad-infinitum. All of these places and names and things are tossed at us over and over and nothing is ever explained, nothing ever clearly defined. It’s sink or swim with this one, and unfortunately, I sank.

“Obelisk” by Stephen Baxter is about Wei Binglin, a captain whose transport ship, the Sunflower, experiences a serious accident en route to Mars. Despondent over the accident, he retires and teams up with a con-man named Kendrick, who convinces Binglin to support the construction of a monument in honor of a Chinese explorer who was one of the first to the Red Planet. Along the way, as the construction begins and Mars experiences a kind of industrial boom (due in large part to the monument), Binglin’s guilt prompts him to adopt a young girl whose parents died in the Sunflower accident. The bulk of the story revolves around the continued construction of the monument and the relationship between the three principals. It’s a pretty good story, but it could have been a great one if there had been more character development. The rather tragic ending suffers a bit from a lack of better character definition.

Alastair Reynolds’ “Vainglory” is the kind of “big idea” science fiction that I enjoy. Loti Hung is a rock cutter, a sculptor whose canvas is most often whole asteroids, some nearly as big as moons. When she is commissioned to sculpt one floating around Neptune into the head of Michelangelo’s David, she jumps at the chance. The money secured by such an ambitious project will set her up for years. Of course, this all happened in the past, as the story begins with Hung being investigated by a private dick who claims that people were killed during the work. Said private eye is trying to determine if Ms. Hung knew of the deaths and if she is culpable. I’ll say nothing more about the plot, other than it’s a good one. I would have liked a more complete and satisfying ending, but I’ll take it.

An Owomoyela’s “Water Rights” is about what happens when the water spigot is turned off. Jordan is a lady who lives on an orbital habitat whose water supply from Earth is suddenly cut (through sabotage it’s believed). This habitat contains a lot of people, and thus it’s natural to assume that chaos will ensue when the water runs dry. The problem is… chaos doesn’t ensue. There’s some disruption and anxiety right at the beginning of the ordeal, but as the crisis evolves, nothing much happens. There are discussions about what can and cannot be done to ration. Jordan is in the thick of this discussion due to her bulk gardening and its need for water, but otherwise, it’s a pretty bland story. The basic premise is that this so-called “crisis” may wind up being the best thing to happen because it will force these orbital colonies to become self-sufficient, thus allowing them autonomy from Mother Earth. A reasonable end result, but this concept alone wasn’t enough in my mind to make for an interesting read.

We end on a positive with “The Peak of Eternal Light” by Bruce Sterling. Set inside the harsh crust of Mercury, a very strict and conservative Indian culture maintains the purdah marital tradition. There is marriage, but the genders cannot live together and are instead forced to meet only occasionally for ceremonial and conjugal duties. It’s a matriarchal society, so the women have control. That sometimes causes Pitar, our male principal, some consternation. But his wife Lucy is a reasonably thoughtful, gentle soul with whom he engages in serious conversation. They talk about all kinds of things, from gender politics to child rearing, to water supplies, to what’s going on in other parts of the solar system. That sums up the story, and based on that, you may think it’s rather dull. Not at all. The relationship between Pitar and Lucy is so pleasant that even though it’s based on a culture quite foreign to me, the main characters are comfortable in their own skin, in their marriage, and that makes their life on blazing hot Mercury bearable, and surprisingly, enjoyable. They even take the time to ride bikes together in the end, and who could complain about that?

So that’s it. To sum, the Cadigan, McAuley, Reynolds, and Sterling entries were the stand-outs for me and will certainly make your purchase worthwhile. Some of these have already even been picked for “best of the year” anthologies. On balance, however, I found this sequel to be a little less impressive than Engineering Infinity. But I hope the editor and Solaris continue with this series, as we need anthologies about big ideas in this genre. We don’t have enough.