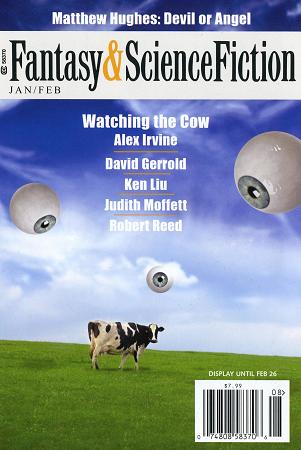

Fantasy & Science Fiction, January/February 2013

Fantasy & Science Fiction, January/February 2013

“Watching the Cow” by Alex Irvine

Reviewed by Louis West

This issue of F&SF contains a diverse and (mostly) entertaining selection of SF, horror, and fantasy stories. Many of the authors have a long history of producing award-winning work. For the most part, that excellence is displayed throughout this issue.

“Watching the Cow,” by Alex Irvine, is masterfully told. Once started, I couldn’t stop. I had to know how it would end, and the end was nicely unexpected. This story could be viewed as a veiled warning to scientists and technologists alike that the consequences of mistakes can have a far greater impact on humankind than ever before.

Ariel, the genius of the family, has accidently blinded two million teens who had been playing a game using VR goggles. And two of the kids were her brothers. But it wasn’t a physical blindness. All the parts still worked. The brain simply had stopped processing the visual data. The kids didn’t seem bothered at all, although the parents freaked and conspiracy theories thrived.

Ariel was determined to fix the problem, and her angry brother believed her. Instead of sight, all the kids could now mentally network with each other. Ariel did eventually find a solution, but it didn’t change the kids back to what they’d been before.

This story is told from Ariel’s brother’s POV. It follows his emotional roller-coaster ride as he deals with what’s happening to his kids, their lack of reaction, keeping the secret that his sister had caused the problem and wondering when the FBI will finally catch up to him and Ariel. A pleasure to read.

David Gerrold’s “Night Train to Paris” is an elegantly constructed horror story that quickly draws you into its clutches—the inevitability of having to ride the night train, the social underbelly of the Milan train station, the seemingly idle artistry of the protagonist’s amateur photography, Claudio’s unrelenting need to talk (the passenger sharing the protagonist’s cabin), the grinding descent into anxiety as the whispered mysteries of the train are revealed, and the almost casual way in which we learn that Claudio was not who we thought he was and how close to death the protagonist had come.

I am not a fan of horror with its crass tools of gore, screaming, and stupid characters. But this I enjoyed. It relied solely on the purity of the mundane to pull back the edges of reality and give us a peek into what might lurk beyond.

“A Brief History of the Trans-Pacific Tunnel,” by Ken Liu, explores an intriguing alternate reality set in 1961 when Japan has become a global power, the trans-pacific tunnel has rescued the world from global depression and WW II has been averted. Unfortunately, all these economic successes have also perpetuated the myths of racial superiority as reflected in the stratified social environment in which Charlie (Formosan) and Betty (American) discover love.

The author does an excellent job of outlining the technology used to build this 6,000 mile-long deep, undersea tunnel and the underground waypoint called Midpoint City. Of course, earthquake risk is flippantly solved by the use of “earthquake-proofing.” But Charlie’s personal story from his uniquely Formosan perspective is so strong that I readily forgave that issue.

The challenges of this vast construction project are similar to those faced in every major 19th and early 20th century undertaking, from America’s trans-continental railway to the Panama Canal–worker safety. For Charlie, his greatest nightmares were of the Chinese prisoners deliberately sacrificed to protect the deep tunnel when they were forced to hopelessly fight against a flood from a pocket of undetected slush and water. These were supposedly hardened Communist rebels, but instead were nothing more than common men, some incarcerated for stealing money to feed their families. Betty tells Charlie that her son back in America is riding buses with Negros to protest segregation. At first, Charlie is bothered by this American obsession to draw “attention to things that other people may prefer to keep quiet, to ignore and forget.” However, as his relationship with Betty restores his passion for life, he finally decides to find a way to “make the secret a bit harder to keep” because “That counts for something.” A must read.

Matthew Hughes’ “Devil or Angel” is pure life-and-death, heaven-and-hell fantasy flavored with a heavy dose of creative absurdity. It’s not just a love story, but a story about great love that can transcend death itself. The author’s tongue-in-cheek treatment of love, heaven, hell, reincarnation and angelic perfection was great fun to read.

Jason, a very successful businessman, who can have any woman he wants, doesn’t meet the one-and-only “her” until on a flight moments before it’s rammed by another plane and everyone dies. We next find Jason in that greatest of all soul recycling plants, purgatory. Angel, a multi-body singular entity, keeps Jason out of heaven and away from his true love. But that doesn’t stop him. He just has to prove that perfect angels can make a mistake and somehow attract the assistance of a pair of sword & sorcery heroes, who are also star-struck in love with each other, to defeat the evil that threatens the very fabric of heaven itself.

“This is How You Disappear,” by Dale Bailey, is frighteningly depressing since it reflects the real-life struggles each of us face to not become irrelevant, to not become old and discarded. Life will eventually pass us by unless we fight each and every day to remain involved, to be purposeful.

Albert E. Cowdrey’s “A Haunting in Love City”—I’m not a fan. Although the author is an accomplished F&SF writer with several awards, this story just did not work for me. A third of the story was spent on background exposition, another third building towards a brief scene of high tension action before fading away again.

“The Blue Celeb,” by Desmond Warzel, is a down-home-in-Harlem supernatural story as experienced by Bill and Joe, two Vietnam vets who’d been barbers ever since coming back. The pace is easy, rambling like the conversation in a barbershop, the style a bit crazy as to be expected from two survivors of a war. But the tale tests the bounds of what passes for reality for most of us.

A Blue Celeb car shows up one day in front of Bill and Joe’s barbershop, a car no-one claims and that their police-buddy friend says is properly registered but doesn’t belong to anybody. The only problem is that, when a local drug dealer tries to steal it, he shows up dead later that night, hit by a bus. Days later two teens get in it, and are later found squished from a 6-story fall after getting chased from the apartment they were trying to burglarize.

Bill and Joe had always considered themselves “Day people.” But the night two drug dealers shot it out and killed a little girl, Joe went manic, grabbed the girl’s body, stole his cop-friend’s car, and hurried back to the Blue Celeb. It was a wild hope on his part that maybe this car of death would also give back life. It didn’t work, or so he thought, until he learned that the girl had sat up in the ambulance free of injuries. After that, he and Joe weren’t day people any more—they knew too much, they’d become “part of the cover-up now, keeping a lid on the night so the day people can go on fooling themselves.”

A must read.

Robert Reed’s “Among Us” tells of the search for Neighbors among us, their presence betrayed by alien bacteria found in everyday city sewage. Trailing the bacterial clues back to their sources, a secret quasi-government-funded group sought to better understand these Neighbors and whether they were just tools of an off-world alien intelligence or something else. The story moves ahead nicely with a slowly growing level of mystery and tension. Unfortunately, the end fell absolutely flat for me. I was disappointed, especially since the author is well-known for his excellent SF novels, novellas and short-stories.

“Ten Lights and Darks,” by Judith Moffett, is a tale about Mike, a reporter assigned to write a story about dog whisperers, who learns that he has a natural talent to speak telepathically with dogs. He doesn’t believe it, even fights against it, but his growing closeness to his new girlfriend leads him down an exploratory path that opens his mind to new realities. A light-hearted treatment of a fringe topic that some readers may embrace with all seriousness.