"Fellow Americans"

"Computer Friendly"

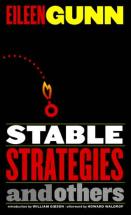

By now just about everybody knows that Eileen Gunn finally has a book out. Like Ted Chiang, Kelly Link, and a handful of others, Gunn’s output to date consists exclusively of short stories. And it seems the quality of her work is inversely proportional to the quantity. Any reader who came across an Eileen Gunn story in an anthology or a magazine immediately wanted more. Here’s more at last.

By now just about everybody knows that Eileen Gunn finally has a book out. Like Ted Chiang, Kelly Link, and a handful of others, Gunn’s output to date consists exclusively of short stories. And it seems the quality of her work is inversely proportional to the quantity. Any reader who came across an Eileen Gunn story in an anthology or a magazine immediately wanted more. Here’s more at last. Gunn’s stories are funny, even laugh-out-loud funny in places, but never in the places you’d expect. And they’re just as often simultaneously funny, unnerving, and strangely optimistic. There’s a subtlety at work that belies the easy laugh, or the light, accessible tone. Her work reminds me of Terry Bisson’s, whose outlook is basically comic but also fundamentally humane.

"Stable Strategies for Middle Management," possibly her best-known story, takes literally the notion that a job can really change a person. In this case, employees of a bioengineering firm advance their careers by having their genomes altered. The narrator is turning into an insect, leading her to, among other things, try to suck the blood out of a co-worker during a marketing meeting. Still, she’s evolving characteristics that will help her succeed in business without really trying (much). Anybody who’s done time in corporate America will recognize themselves in at least one of the characters (and Gunn keeps a fairly large cast busy in only about 5,000 words). Her blend of the literal and the satirical/allegorical is seamless, in what has to be one of the funniest and most truthful sf stories to come out of the late 1980s.

"Fellow Americans" is an alternate history in which Barry Goldwater was elected President in 1964. Gunn skillfully gives us alternating points of view, too, showing the world of 1991 through the eyes of the retired ex-pres who nuked Vietnam, the still-ambitious RFK, and a game-show host named Richard Nixon. None of this should work, but Gunn pulls it off beautifully. Her depiction of a Nixon who found peace in his new profession is not just funny but oddly touching, whatever your politics. "Tell all the Truth but tell it slant," Emily Dickinson advised; few alt-historians have taken her suggestion as close to heart as Gunn.

Recently I was asked by a fan of Bradbury and Clarke if I knew any stories that blew my mind like the early classics of modern sf. "Stable Strategies" and "Fellow Americans" immediately came to mind, and these two stories alone make the book worth getting.

But as they say in marketing, wait, there’s more. "Computer Friendly" is a good example of showing over telling: we get to know the dystopian world through a seven-year-old girl’s point of view. She’s precocious but not savvy enough to understand what the reader gleans from such well-chosen details as a test question: "Why is it important for everyone to learn to obey?" Ties of affection, movingly depicted, lead the girl to explore the world’s computer network, encounter avatars of pop-culture and software references, and finally arrive at an unexpected source of hope. Added bonus: Gunn’s kids talk like real kids, as opposed to an adult’s idea of what kids should sound like.

"The Sock Story" ponders the fate of footgear lost in the laundry, striking out in directions loopy even for a story that tackles such considerations. This short-short displays two notable Gunn characteristics: a tale that seems to come from an oral tradition, and the two faces of control: getting it and giving it up.

Order versus chaos appear again in "Coming to Terms." A daughter sorting through her estranged father’s belongings starts to wonder what pattern is created by those left-behind things—especially the books with their dated handwritten annotations. And which direction does time flow, anyway? It’s more a mood/slipstream piece than sf/f, drawing its strength line by line.

"Lichen and Rock" reads like a spoken folk-tale recorded by an anthropologist, but is set in a far-future pastoral. "The woods sheltered them, the water fed them, and small electronic devices told them stories." In the wake of a bloodless invasion by "the carp-eyed people," young Lichen returns from a long term at school to find her family and neighbors have undergone Bosch-like transformations, like mouths on kneecaps or fingers growing out of ears. Lichen decides her parents want reassurance that they did the right thing by sending her away. Lichen answers that question and learns to think for herself, in an ending that prescribes passionate engagement with the world, right or wrong. This evocative story is the tour de force standout of the book.

"Contact" and "What Are Friends For?" consider human-extraterrestrial interaction. Neither is truly groundbreaking, but both offer original insights and entertaining twists. The former, set on an alien planet, depicts first encounters between an anthropologist from Earth and an intelligent planetary native, one of a race of batlike creatures that have abandoned high tech because of the strain it put on their nervous systems. The native’s telepathy allows for the exchange of ideas (in Russian, for once), but true understanding is not so easily achieved. In the latter story, a gang of thieves and con-artists think their lives haven’t changed much since tentacle-headed aliens conquered Earth. Our narrator stumbles across the alien’s master plan, decides he wants nothing to do with it, and buys a planetary reprieve by introducing the aliens to practices unique to humans. It’s as if the cast of Reservoir Dogs saved the day.

"Ideologically Labile Fruit Crisp" is an essay disguised as a recipe, with notes suggesting guidelines for choosing the optional ingredients: "If you’ve arranged the fruit in a pattern, skip the thickener, because it will lie glutinously in a layer, like the economic benefits of tax cuts for the rich."

"Spring Conditions" is an early story written for a contest judged by Stephen King, and highly praised by the Master of Modern Horror. What is that thing bobbing beneath the surface of a frozen lake? And "was that a soft slithering in the trees to the right?" Add a dollop of guilt and the result is a brief but effective nightmare.

"Nirvana High," co-written with Leslie What, appears here for the first time. The "special" students at Kurt Cobain Magnet School are just that, with paranormal abilities like teleportation and precognition. It’s still high school, though, and therefore hell for most students. A chemistry exam with life-or-death consequences proves it pays to study; a funeral for a favorite teacher turns into an unlikely celebration of life. The authors shelved this story after Columbine, but I’m glad it’s seen the light of day. Its forgiving, we’re-all-in-this-together outlook is something we need these days.

The last and longest story, "Green Fire," is a round-robin by Gunn, Andy Duncan, Pat Murphy, and Michael Swanwick, written as a serial for Ellen Datlow’s late lamented EventHorizon.com e-zine. There’s a pinch of fact in this story—Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and L. Sprague De Camp really did work at the Naval Air Experimental Station in Philadelphia during WW2. The pinch of urban legend is the crank notion that a battleship disappeared in a teleportation experiment undertaken around that time. This being an sf story starring real-life sf writers, it begins plausibly enough, with an experiment to shield ships from radar by using Tesla coils. Dimension-hopping ensues, and our young, just-published heroes learn how to steer the device, unmask the perpetrator, return the ship safely to base, and agree they’ll never discuss this with anybody. The subject matter sounds silly, but the well-drawn characterizations—especially of Asimov and of Grace Hopper, a WAVE and computer pioneer who really did exist—make this story memorable despite the jokiness. I only wish this fab four could have showed us Asimov’s tour of Quetzalcoatl’s undersea kingdom, but even in a round-robin you can’t have everything.

The collection is rounded out by a hilarious and insightful introduction by William Gibson, a celebratory poem by Swanwick, and an appreciative and funny "Afterwards" by Howard Waldrop. There’s also an anecdote by Gunn, "The Secret of Writing" according to Gibson, which every writer will appreciate.

Eileen Gunn has enough people telling her to write more, or write faster. Alt-country singer-songwriter Lucinda Williams told critics who groused about how long it took an album to come out that if you like the product, don’t criticize the process. If that means another thirty years between books, it’ll be worth the wait.