Edited

by

Storm Humbert

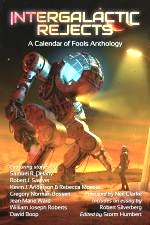

(Calendar of Fools Publishing, June 20, 2025, tpb 294 pp.)

“Pod People” by Rich Larson

“Life After Life After Life” by Christopher Blake

“Almost Time” by Andrew Jackson

“For the Rectitude of Our Intentions” by Stephen Kotowych

“Disclaimer: This Is Not Your Child” by Steve Loiaconi

“Messenger of Death” by William Joseph Roberts

“Tears in the Nursery” by Catherine Wells

“Walk Slowly and Bring a Magnifying Glass” by Marie Croke

“Brigid and the Snakes” by Jean Marie Ward

“Upsized Savior” by David Boop

“Birdsong” by Erica Ruppert

“Encounter over Flanders” by Laurence Raphael Brothers

“On the Last Day You Die” by Sam W. Pisciotta

“Forget-Me-Not” by Gregory Norman Bossert

“Boddah” by Paul Dale Smith

“The Sea Monster” by Amelia Dee Mueller

“Horses of Pazyryk” by Sam Harris

“Collaborators” by Kevin J. Anderson & Rebecca Moesta (reprint, not reviewed)

“Lost in the Mail” by Robert J. Sawyer (reprint, not reviewed)

“The Wyrm” by Samuel R. Delany (reprint, not reviewed)

Reviewed by C. D. Lewis

One common backstory of beloved stories is prior rejection. Everybody who knows what their favorite authors went through to get fan-favorites published is aware how much “no” there is in the world, even if they haven’t themselves submitted stories for publication. Famously-rejected classics include genre-redefining legends like Beatrix Potter, whose early rejection drove her to self-publish her first work at her own expense for friends and family. Apparently keen to celebrate diamonds previously discarded as ordinary rock, Intergalactic Rejects collects works chosen for their history of prior rejection. Twenty stories are included here, seventeen seeing first publication in this volume, and these are reviewed here. The anthology presents each story with its rejection history, and some of those are stories in themselves.

Rich Larson‘s short science fiction story “Pod People” narrates a naturalist’s experience operating a faux-dolphin remote for a team gathering data on animal behavior. The narrator’s place in a pod of wild dolphins depends on his relationship with its members, and soon he’s identifying with their problems and risking his job for their benefit. Pretending to be a dolphin and thinking about his relationship with the dolphins amplifies something that appears in a lot of good science fiction, which is that it puts the reader into the position of considering the humanity of nonhumans and, perhaps, creating more room in the definition of “person” for beings who are wildly different. Part of what connects the narrator to the dolphin he depends upon for his connection to the pod is some shared experience with loss. Though “Pod People” has a number of optimistic elements, the mood that permeates it is melancholy and the narrator seems to be put to the choice between bad choices. But then the purpose of SF is to comment on the present, right?

Set in an asteroid belt orbiting a nameless star, Christopher Blake‘s “Life After Life After Life” narrates the last hours of a mechanical matriarch in a school of techno-space-whales. The protagonists’ migrations, predators, feeding habits, and navigation are described with language that evokes ocean life on Earth, giving one the impression of spacefaring whales communicating in whalesong while defending young from space-sharks and space-whalers while harvesting the bounty of whatever asteroid belt they may inhabit that season (however a season might be measured). Since this isn’t a fantasy, but science fiction, there’s some allusion to the narrator’s creation by humans to harvest valuable materials from asteroid belts, which would explain why they’re made to grow as they harvest material and why they would at advanced age be recycled by their compatriots into young specimens which might more efficiently harvest more material … all while being hunted by humans interested to recover the material they themselves glean from the distant reaches of asteroid belts. This dark scenario—an obviously sentient people created with the ability to replicate and enjoy personal relationships and teach their young, but built to be hunted for profit by their creators—is unfolded slowly enough that one hardly notices the horror backdrop until the climactic battle. The fact that the climax’ resolution can be seen coming doesn’t keep it from providing both emotional resonance and a pleasant hopefulness.

A first-person vignette, Andrew Jackson‘s “Almost Time” opens on the universe’s last human learning about the hibernation tank incident that has cost him his left arm. There’s not much for the narrator to do but perceive the ship’s situation and react; there’s not much plot in the thousand words, but there’s a wealth of imagery and the suggestion in so many details of off-screen adventure and undisclosed backstory. The world feels rich, and the situation interesting, and the anticipation for the next scene is beautifully built.

Stephen Kotowych‘s “For the Rectitude of Our Intentions” differs from the previously-reviewed works in this tome by being set on Earth instead of in space; being told in the third person rather than being related by a first-person narrator; being set in the past in an alternate history rather than being set in the distant future; and being grounded in a magical casting rather than science fiction. Like good alternate history, the work is underpinned by a few facts that stand up to research. Much of the reader’s enjoyment of this piece will turn on whether the reader is inclined to view as entertaining, or offensive, the notion that certain founding documents of the United States were created in a process involving dark magic and intended to be buttressed by a human sacrifice organized by Thomas Jefferson, the completion of which ritual John Adams interrupted at the cost of both their friendship and the protections that would have flowed from the spell. Entertainingly, the question whether black magic and human sacrifice is a cost worth paying for national security is not as absurd as one might have hoped, as men purporting to work for American interests blatantly violate United States law and long-established Constitutional protections (including, as multiple news articles recount, the warrantless detention of bona fide citizens of the United States) while claiming to protect U.S. citizens. If the spell would have worked, would the hypocrisy have been worth the cost? Like a lot of fiction, the work presents some interesting jumping-off points to discuss real world choices.

Steve Loiaconi‘s “Disclaimer: This Is Not Your Child” originated as a submission for a collection of dark user manuals, and it is dark comedy. A read of the nearly 250 words sketches a dismal future in which AI and ongoing school shootings have given rise to a grief-therapy bot that parents should understand is not, in fact, their child; and which must be returned soon because the federal program funding the bots is limited. Complete with reference to a loony Act of Congress bearing a name carefully crafted to have a memorable acronym, and outrageous liability warnings, this really has the feel of an absurdist dark future user manual–or at least its disclaimer page. It would be a better world in which this would not be so close to reality that it’s funny; but the world isn’t better, and this is hilarious.

William Joseph Roberts‘ third-person urban fantasy “Messenger of Death” opens in Ireland on a woman praying for aid before committing a rooftop-access burglary. Like many stories, it begins with a refusal to the call to action. Lots of refusal. The protagonist has no idea she lives in an urban fantasy universe, which may frustrate readers who expect their protagonists to quickly catch on to the games going on about them. Inspired in part by Piers Anthony’s On A Pale Horse, the protagonist finds herself pressed into paranormal service. On the bright side, a busy post-death soul-processing bureaucracy and its streaming online HR onboarding process provide humor while the protagonist flails toward a plot resolution.

Many ghost stories spend most of their time setting up a tragic end and then add a line or two about later haunting: even today, some people say they can still hear a voice…. Catherine Wells opens her ghost story “Tears in the Nursery” with a short Depression-era backstory then delivers the bulk of the tale: a whole lifetime of ghostly interaction. Wells evokes emotion and delivers a strong sense of nostalgia.

Marie Croke plays on the sense people have that things seem smaller as they return after growing up by having the narrator of “Walk Slowly and Bring a Magnifying Glass” experience her shrinking childhood home as a real occurrence. Making visits home physically impossible due to size differences and requiring email and video-calls instead of letters and visits seems to amplify the sense of loss one has in growing away from one’s home and one’s parents.

“Brigid and the Snakes” is a fantasy alternate history by Jean Marie Ward. Brigid prevents Patrick from cursing Ireland while not thinking through the consequences of a spell he had been working, only to inadvertently inspire Patrick to bring snakes to the island through a magical transformation. Readers with strong feelings about Ireland’s native religion, or various waves of Christians who’ve influenced its history, may react more to the depiction of religions and their adherents’ conduct than to the plot.

David Boop‘s dark comedy science fiction short story “Upsized Savior” opens with a celebrity pitch for a for-profit cryogenic service. The dark undercurrent of a real-world snake-oil pitch is deepened with early signs the hero-adventurer celebrity is self-interested and practiced in deceit. The entertaining surprise in the crook’s scheme probably should not be spoiled for readers, but a just-desserts twist conclusion ensures enjoyment.

Erica Ruppert‘s post-apocalyptic science fiction short story “Birdsong” opens on a survivor foraging in the ruins of her village for grubs and dandelions to eat, followed by the death of a newborn. It’s dark. The darkness is part of its rejection history: in a world becoming grimmer, many editors prefer happier pieces. The darkness isn’t a problem: it’s a well-crafted story mood that delivers. If you’d like to inhabit a doomed waste with no hope for a little while in your mind, consider “Birdsong.”

If you love old films with low-budget UFO effects like glowing lights manipulating analog gadget interfaces on an automobile, you’ll enjoy Laurence Raphael Brothers‘ alternate history “Encounter over Flanders” in which British airmen patrolling the skies over WWI Europe risk not only the aircraft marked with the symbols of foreign powers in Europe but really really foreign aircraft with no markings at all. As with the best alternate histories, Brothers offers an alternate explanation why France’s multiple-multiple ace Capt. Guynemer became missing in action (although in this world, multiple accounts eventually confirmed his death in battle, so his status wasn’t “missing” long). There are a lot of takes an author can offer in a tale set in wartime, and those choices can feel a lot more pointed when it’s a real-world war with the kind of death toll associated with World War I; it’s affected many readers’ nations, and many readers’ families. There’s some camaraderie depicted between two pilots from allied nations, and there’s some action that seems to suggest willingness by belligerents to attack noncombatant bystanders simply for being in the wrong place or looking different, and the conclusion may imply prioritization of the current war to the discovery of truths that might affect humans forever. One might discern a critique in any of these facts, and given the gravity of the setting it’s tempting to try. Perhaps there’s a message in pilot comrades, in love with flight, discovering they never need land.

If you liked the dystopian horror scene in the first season of Altered Carbon in which the family of a released inmate was made to receive their young daughter in the body of an older man, you’ll appreciate the opening in Sam W. Pisciotta‘s “On the Last Day You Die” in which a soldier discovers he’s been reanimated by his sergeant into the body of an old man. It’s a dark world: the old man was an unsympathetic civilian, and the military doesn’t seem to acknowledge anything like human rights. The worldbuilding is deftly delivered, including a military so tight with resources it won’t let exhausted soldiers just die. In a world so dark, one isn’t expecting an uplifting conclusion (though if one thinks too long how the reanimation mechanics work, it’s right back to darkness). It’s interesting, short, and offers an escape-as-victory conclusion.

Gregory Norman Bossert‘s “Forget-Me-Not” offers the entertainingly outrageous premise of a lint trap that mysteriously collects hair and fibers that could not belong to its laundering owner. The main character’s compulsive effort to collect, separate, and evaluate the mystery materials is exceeded by some unseen force’s work to sort and organize what he merely separated. It’s so ridiculous, it’s hard not to wonder where this could possibly be going. Obsession consumes the protagonist, whose vision for how the lint trap material should be organized stands at odds with the force that corrects his intervention. One hopes the main character will, in pursuit of his weird mission to make sense of the lint trap collection, stumble into a relationship with a research librarian on whom he relies to find photos to help him understand what might be materializing in his apartment. One hopes a lot of things. The rejection history suggests selling the story ran afoul of genre selection: who represented the market for a weird fantasy like this, which doesn’t produce faeries and doesn’t lead to romance and, while creepy, isn’t really horrifying except in a piteous kind of way? But this may be for you, if you like the weird and the fantastic and the socially disconnected and the obsessed. The glory of this piece is that one can be completely certain that it’s not trying to be somebody else’s story or follow some kind of formula: it’s going where it’s going, and if that’s your direction it’s for you.

Paul Dale Smith‘s “Boddah” opens on a science-fiction Kurt Cobain who, through the miracle of gene therapy, lives on through an anointed successor centuries after the original. And records new work: there’s money in re-launching a lost celebrity. Between the gene-manipulated man who’s undertaken the Kurt Cobain role and the doomed history of the original and the various pressures to perform or try addictions likely to end his life, there’s plenty from which to build drama. “Boddah” presents a dark view of life as an entertainer backed by investors who expect a return, confronted by doubts about themselves and their work, and offered a path to turn off the pain. The climactic choice is surprisingly uplifting.

Amelia Dee Mueller‘s “The Sea Monster” is a fantasy that seems to be a commentary on institutional denial: she can see her co-worker is a sea monster, complete with tentacles and a clacking beak, but others in the workplace dismiss these details as insufficient to draw a conclusion, or above their pay grade, or not worth taking up with HR. The excuses offered to explain why it’s no big deal are crafted from the normalizing rhetoric offered for why people should tolerate bigots or creeps. If this isn’t clear enough, the narrator’s reminiscence on the complaints of others echo the stories one hears from and about friends and relatives in abusive relationships. The ignored workplace complaints lead to the harms one expects, including the protection of wrongdoing sea monsters by their sea monster chief executive. The piece’s strength is its clarity of message, and the force of its climax comes from the reader’s desire to see the same fate befall real-world monsters.

Sam Harris opens “Horses of Pazyryk” in a museum where a bullied child seeks shelter when his coat is stolen by bullies in winter. It’s unclear there’s a science fiction or fantasy element in the story; the child’s imagination that hears the screams of horses in the museum exhibit, slaughtered to serve as grave goods for a mummified master, is not really presented as a fantasy element. The story takes place in several settings: the museum, where the narrator reacts to the horses and his hatred of the mummy; the street, where he’s beaten and robbed by bullies whom no authority stops; and his apartment, where he’s berated by his father and his father is berated by his grandfather. The messages this tale has about bullies aren’t new, though of course they’re true to life: passively tolerating a bully’s abuse really does invite further and escalating abuse, and beating the tar out of your bully really does reach the bully with the message his fun is over.

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.