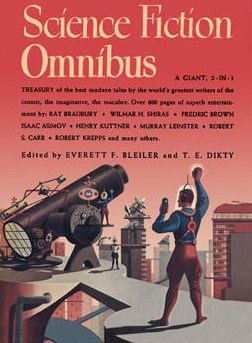

Science Fiction Omnibus

edited by

Everett F. Bleiler & T. E. Dikty

(Garden City Books, 1952)

by Robert Brown

Introduction

Everett F. (Franklin) Bleiler (1920-2010 ) and T. E. (Thaddeus Maxim Eugene) Dikty (1920-1991) were pioneers. For almost a decade (1949-1958) their The Best Science Fiction Stories annual collections paved the way for many more to come, and several aspects of their format are still in use today, more than sixty years later.

From 1949 through 1954 the series was compiled and edited by both Bleiler and Dikty, as well as the companion volume Year’s Best Science Fiction Novels (which also included novellas) from 1952-54. Both volumes, edited by Bleiler and Dikty, would cease in 1954. However, the now retitled The Best Science Fiction Stories and Novels, under Dikty’s sole editorship, would continue with three more volumes: 1955, 1956, and 1958.

The aforementioned final three Dikty volumes would begin with semi-lengthy introductions titled “The Year in Science-Fiction.” Not only did he speak of the state of science-fiction during each particular year – the stories, conventions, magazine launchings and demises, and more – but he would also include notice of significant world events in various disciplines, scientific and otherwise. We can see this influence today in the introductions to several annual Year’s Best SF collections, most notably in Gardner Dozois’ lengthy introductory “Summations” with which he prefaces each of his annual collections.

The aforementioned final three Dikty volumes would begin with semi-lengthy introductions titled “The Year in Science-Fiction.” Not only did he speak of the state of science-fiction during each particular year – the stories, conventions, magazine launchings and demises, and more – but he would also include notice of significant world events in various disciplines, scientific and otherwise. We can see this influence today in the introductions to several annual Year’s Best SF collections, most notably in Gardner Dozois’ lengthy introductory “Summations” with which he prefaces each of his annual collections.

Also paying homage to Dikty’s “The Year in Science-Fiction” style were the late Martin H. Greenberg and Isaac Asimov, co-editors of the long-running, 25-volume DAW series (1979-1992) Isaac Asimov Presents The Great SF Stories (1939-1963), wherein each introduction would speak to historical world events of each year as well as those inside the “real world” of SF.

Bleiler and Dikty’s pioneering efforts and their long-felt influence is with us today, ably carried forward by any number of Year’s Best SF annual collections. But they were the first, and below Robert Brown takes a story-by-story look at an omnibus edition of the first two years of this groundbreaking series, 1949 and 1950.

— Dave Truesdale

This is an omnibus of the first two annual editions of the first “Year’s Best SF” series. Some claim the “golden age” of sf spanned the years 1939-1946, others make the same claim for the years 1950-1956. I’ve always believed that every year has seen the publication of terrific sf, and this volume is evidence in the affirmative, at least for 1948 and 1949. So return with me to the years when four of the top five sf writers were Lawrence O’Donnell, Henry Kuttner, C. L. Moore and Lewis Padgett!

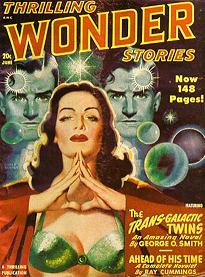

Ray Bradbury‘s “The Man” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, Febuary 1949) is a fable about faith and meaning, involving an excitable spaceman and his emotionally unstable Captain who land on a planet just after a very special visitor has appeared and departed, leaving his message of peace. The implication is a visitation by Jesus, though Bradbury offers only an—intentionally—vague representation of the warm and fuzzy aspects of the Christ legend. The real message is that all this rationalism and reason and science is such a drag, man, and why are we out here in space anyway? An early New Wave story with a pious twist, basically.

Martin Gardner‘s “Thang” (Comment, Fall 1948) is a jape in which a giant entity who devours planets as a light snack finds itself the delectable bon bon of something greater still in a cosmic reimagining of the chain of life. Though played for laughs, it does provide food for thought.

“Flaw” (Startling Stories, January 1949) by John D. MacDonald assumes for the sake of a gothic widow’s tale that the universe isn’t expanding, rather the solar system is shrinking, and the astronauts voyaging boldly out into the dark are in for a surprise upon their return. The focus here is more on the storycraft and less on the plausibility of the concept. (The ship is gone for a short while, so if the Earth were shrinking fast enough to make the difference it makes in the course of the story, the Earth would either have been as large as the visible universe at the beginning of time, or would have long since shrunk to a singularity. But I don’t think MacDonald cared.)

“Flaw” (Startling Stories, January 1949) by John D. MacDonald assumes for the sake of a gothic widow’s tale that the universe isn’t expanding, rather the solar system is shrinking, and the astronauts voyaging boldly out into the dark are in for a surprise upon their return. The focus here is more on the storycraft and less on the plausibility of the concept. (The ship is gone for a short while, so if the Earth were shrinking fast enough to make the difference it makes in the course of the story, the Earth would either have been as large as the visible universe at the beginning of time, or would have long since shrunk to a singularity. But I don’t think MacDonald cared.)

“Flaw” is one of the more prominent examples in this book of the difference between the fiction production of the pulp era and that of today. Stories in those days were produced quickly, and often with only a single person between writer and print: the editor of the publication. No crit groups, no editorial edifice, no how-to library. A man, a typewriter; another man, a blue pencil: a streamlined process which resulted in breezy, fun, but often flawed work which—except in the case of the truly exceptional “classics” we revere today—simply doesn’t withstand even cursory scrutiny.

“Flaw” is also one of several stories which inform the reader that no communication is possible between the ships and Earth. This was before teevee, of course, and before any person had ever gone into orbit. So perhaps this incommunicado motif is a result of narrative necessity, or perhaps it is due to lack of knowledge. In either case it gives the stories a strange, closeted feel.

In “Knock” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, December 1948) Fredric Brown adds a layer of play to the game by engaging in a sophisticated bit of metafictional deconstruction…on one of his own earlier stories. He opens with his own classic twenty-word stunner, dragging the concept of the knock on the door of the last man on Earth through a few twirls and capers, emerging with a tale of Adam and Eve triumphing (sort of) against an ET menace. Nonsensical when broken down, it convinces as it is being read, which is all that really counts.

Another Fredric Brown tale, “Mouse” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1949) opens with a flying saucer landing in Central Park, follows the investigation of the vessel and its dead pilot through to the chilling implication that the ET within didn’t perish in the ship after all…concluding with an unsuspected development which I am confident will pounce on you and give you pause.

Robert W. Krepps provides an insanely odd, and completely nonsensical farce in “Five Years in the Marmalade” (Fantastic Adventures, July 1949) in which a Martian regales two travel-weary Terrans with tales of his magical technology which allows him to travel to imaginary places, so long as the places are strongly-enough established in cultural memory: Lilliput, for example. So one of the men extemporizes Marmalade to mock him, and the little Martian engages his gadget…only to find himself on the surface of the teaser’s brain. Spiteful, the Martian sets up his camp to live a few years right on the poor man’s cerebral cortex. It’s absurdly charming, inventive, and daft.

Robert W. Krepps provides an insanely odd, and completely nonsensical farce in “Five Years in the Marmalade” (Fantastic Adventures, July 1949) in which a Martian regales two travel-weary Terrans with tales of his magical technology which allows him to travel to imaginary places, so long as the places are strongly-enough established in cultural memory: Lilliput, for example. So one of the men extemporizes Marmalade to mock him, and the little Martian engages his gadget…only to find himself on the surface of the teaser’s brain. Spiteful, the Martian sets up his camp to live a few years right on the poor man’s cerebral cortex. It’s absurdly charming, inventive, and daft.

The stories herein are not all light entertainment, however. It would be hasty to draw too many conclusions about the state of science fiction from the contents of such a book as this one, a product of the informed discernment of two men, editors, scholars, and fans, but I think some idea of what sf was capable of and what it was used for in that period is clear, the selections’ tendency toward the fablistic, for instance.

There are morals aplenty, but specifically I refer to the sketchy aspect of the fable. In our times literary realism has flavored all fictional aspiration. It has been the dominant mode for half a century, esteemed by the estimable, supported and favored by the publishing armature. In the late 1940s, mimesis had not yet risen to dominance, and the penny-per-worders who supplied the column inches for sf mags resorted to the storytelling arts of yore to ply their trade.

This selection of stories is subject to the taste and whim of the editors, and they were hardly in a position to send extra-textual messages across unknown decades to us today regarding the nature of pulp narrative and the evolution of the sf story which lay in their own future, but a general distinction can be drawn even from this sampling: sf stories—and stories in general—were written to a different standard and for a different audience before 1960. Old sf was airier and more generalized; today’s sf—just as with most fiction—is denser, richer, and more particularized. The needs of story have become suborned to the dictates of psychological naturalism. Neither form is superior, but they are very different. It’s all a matter of taste. I think in recent years the pendulum has begun to swing back toward the exaggerated, the emblematic, the incredible. Only time will tell where the sf story is headed.

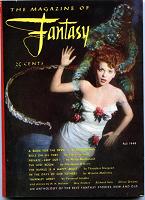

A good example of the story values of this earlier age is Theodore Sturgeon‘s “The Hurkle is a Happy Beast” (The Magazine of Fantasy, Fall 1949). A whimsical tale of invasion which falls apart at the end, it nonetheless provides a very different take on the war of the worlds, and suggests strangeness beyond human ken as well as can be accomplished with merely English prose. But Sturgeon makes no attempt to fully rationalize the action of the story or fully detail the characters or their motivations. They are mythemes, engaged in a narrative which imparts the special affect of a myth, albeit in this case a modern myth. Sturgeon was certainly capable of providing mimetic detail—he’s one of the pioneers of doing just that in science fiction, after all—but in this case such detail would not have served the interests of the story, nor perhaps the reader. It’s a lark.

A good example of the story values of this earlier age is Theodore Sturgeon‘s “The Hurkle is a Happy Beast” (The Magazine of Fantasy, Fall 1949). A whimsical tale of invasion which falls apart at the end, it nonetheless provides a very different take on the war of the worlds, and suggests strangeness beyond human ken as well as can be accomplished with merely English prose. But Sturgeon makes no attempt to fully rationalize the action of the story or fully detail the characters or their motivations. They are mythemes, engaged in a narrative which imparts the special affect of a myth, albeit in this case a modern myth. Sturgeon was certainly capable of providing mimetic detail—he’s one of the pioneers of doing just that in science fiction, after all—but in this case such detail would not have served the interests of the story, nor perhaps the reader. It’s a lark.

ETs play an important role in another loosely-fitted fable of slightly more serious intent, “Easter Eggs” by Robert Spencer Carr (The Saturday Evening Post, September 24, 1949). Two Martian ships arrive on Earth, one to the US and the other to the CCCP, and are—somewhat predictably, alas—caught up in Terran geopolitics to the point that they make war on each other. The Martians aren’t convincingly alien, rather they seem like naïve humans. This parablistic use of the Other is another example of the difference between literary sf and fablistic sf. The ending is a cheap dodge, involving unnecessarily withheld information, which nonetheless provides Carr with a chance to moralize about the incipient Cold War and human short-sightedness (I do not disagree with his diagnosis, but his medicine is a bit strong). Sadly, we still had to work through several decades before the foolishness of the conflict finally resolved, though I wonder if we’ve really ever recovered from it.

Another—though logically-sound—example of the whimsical approach is an early alternate history story, “The Life-Work of Professor Muntz” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1949), in which Murray Leinster (pseudonym of Will F. Jenkins) follows up his famous story “Sidewise in Time” with a logical-loop of a tale involving a lout who comes into possession of the device which the hapless, late eponymous inventor used to create a connection to alternate nows. It turns out the lout is the unintentional cause of the professor’s death, and by the end of this story, he has also unwittingly destroyed the device which the professor invented, but not before it has rescued him from the nefarious schemings of his boss. Ironies pile on. Considering the angst-ridden, gruelling uses to which alternate realities are put these days, this story is positively pallid and vapid. It’s also a terrific bit of sfnal satire.

The team of Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore provide the most outstanding examples of both the whimsy and the fablistic types, one more sfnally interesting, the other a seamlessly perfect example of mid-20th century short storycraft, a marvel of compression, concision and concept.

The more sfnal story, “Ex Machina” (as by Lewis Padgett) (Astounding, April 1948) concerns the hopeless sot professor Gallagher, who in this episode is desperate for cash and must outwit himself, for he has awoken from his drunken slumber to find that his booze disappears  every time he attempts to take a drink, and he is intellectually blunted without his liquor. The mystery is unsolvable, but the working out of the secret is fun, with legal proceedings for murder running in the background. It’s all absurd, but the transparent robot assistant provides an ominous coda when he declaims that he is in fact the Prime Mover. A lush bouquet of spirit and a saucy binge.

every time he attempts to take a drink, and he is intellectually blunted without his liquor. The mystery is unsolvable, but the working out of the secret is fun, with legal proceedings for murder running in the background. It’s all absurd, but the transparent robot assistant provides an ominous coda when he declaims that he is in fact the Prime Mover. A lush bouquet of spirit and a saucy binge.

The masterpiece of narrative technique is the sinister and painfully clever “Happy Ending” (as by Henry Kuttner) (Thrilling Wonder Stories, August 1948). A man enters a fortune-teller’s tent and learns that he is being hunted by an unspeakable horror, and the chase is on. A mobius strip of narrative which reveals all, but only at a price. Though hardly profound, this is one of my all-time favorite stories, and is worth seeking out.

Three of Ray Bradbury‘s Martian Chronicles stories are reproduced here: all of them fables. “Mars is Heaven!” (“The First Expedition” in the book) (Planet Stories, Fall 1948) relates the tragedy of the first humans on Mars. The natives defy them by luring them into a trap. They appear as the Earthlings’ departed loved ones in a reproduction of the American myth of the Midwestern small home town. The plan works, and the flies are dispatched by the spiders. A sensible response to first contact, and a different kind of Mars adventure, one which no doubt startled the contemporary reader.

In “Dwellers in Silence” (“The Long Years” in the book) (Maclean’s, September 15, 1948), after most of the human colonists fled back to Earth in an emergency, a man who remained behind on Mars and whose family perished in a plague awaits rescue in the company of autmatons formed in the image of his loved ones. The rescue when it comes is too late. It’s a poignant tale, though it strains credulity. But of course, Bradbury wasn’t aiming for credibility, rather the affect of modern myth.

In “And the Moon Be Still as Bright” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1948) an expedition to Mars meets tragedy when one of its crewmen goes native and begins murdering the others in order to save the Martian ruins from the depredations of human contact. It’s hard not to identify with the killer’s trepidation given what we know about human nature and tourism and pollution and litter and such, though the action of the story is off-kilter and logically absurd. No one heard the shots as the killer guns down several of the crewmen? There is a forced communion between the killer and the Captain, who resolves to take up the gauntlet on behalf of the Martians, albeit in his own way, on his own terms. There’s no ostensible reason for this protectiveness; perhaps it’s Aresian voodoo.

In “And the Moon Be Still as Bright” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, June 1948) an expedition to Mars meets tragedy when one of its crewmen goes native and begins murdering the others in order to save the Martian ruins from the depredations of human contact. It’s hard not to identify with the killer’s trepidation given what we know about human nature and tourism and pollution and litter and such, though the action of the story is off-kilter and logically absurd. No one heard the shots as the killer guns down several of the crewmen? There is a forced communion between the killer and the Captain, who resolves to take up the gauntlet on behalf of the Martians, albeit in his own way, on his own terms. There’s no ostensible reason for this protectiveness; perhaps it’s Aresian voodoo.

I hadn’t read Bradbury in a long while. Reading him now provides me with little of the pleasure it gave me when I was a lad. I think Ballard provides for my much older self what I once sought in Bradbury on the rare occasions when I need it. Ballard doesn’t dismiss reason, instead finding fault with human frailty, an approach I appreciate. Although I think the main difference is the psychological acuity of Ballard’s characters, and the heft of detail. I guess I’m a product of my era, responding to the careful simulation of reality over the comforting vaguery of myth.

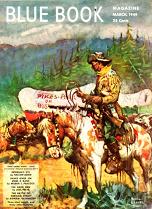

In “Doughnut Jockey” (Blue Book, May 1948) Erik Fennel takes a nuts-and-bolts approach to the future of space exploration, in a story about a supporting lift engine system that was never utilized, as far as I know. Instead of a single rocket, launch into orbit in this future is accomplished with the aid of a “doughnut,” a kind of tugboat (or “pushboat” I suppose) which provides most of the lift, taking the place of rocket stages. The doughnut is piloted, and returns to the ground as the interplanetary ship achieves escape velocity. In this story a dedicated and talented doughnut pilot is itching for his chance to go to Mars, but fate intervenes when a desperately needed shipment of medicine to prevent a plague on Mars is on the line. Office romance complicates the proceedings. A good example of the “hard sf” tradition, although in a “slick” magazine style, light on the rivets and heavy on the courtship banter, Clarke as written by Cartland.

I also find it intriguing that the “hardest” sf story in the book appeared in a non-genre publication.

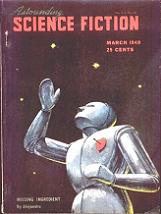

Wilmar H. Shiras appears with a famous story and its sequel. “In Hiding” (Astounding, November 1948) and “Opening Doors” (Astounding, March 1949, cover at right) concern Timothy, a mutant genius who struggles to maintain his secret life and his dignity as a small boy in a small town elementary school, but whose secret is discovered by a remarkable guidance counselor who aids Tim in locating more of his kind. There’s a lot of regressive child-rearing guff in here, and some religious apologia, as well as a provocative interpretation of the pedagogical value of chess, but the lingering sense of the limitations of the human mind and the frightening possibilities of the unfettered genius are what mark the stories as memorable. Very much in the tradition of Van Vogt and I’d say formative in the development of Orson Scott Card’s Ender stories. (In particular Tim’s literary life reminds me of Peter and Valentine Wiggin’s development in “Ender’s Game.”)

Wilmar H. Shiras appears with a famous story and its sequel. “In Hiding” (Astounding, November 1948) and “Opening Doors” (Astounding, March 1949, cover at right) concern Timothy, a mutant genius who struggles to maintain his secret life and his dignity as a small boy in a small town elementary school, but whose secret is discovered by a remarkable guidance counselor who aids Tim in locating more of his kind. There’s a lot of regressive child-rearing guff in here, and some religious apologia, as well as a provocative interpretation of the pedagogical value of chess, but the lingering sense of the limitations of the human mind and the frightening possibilities of the unfettered genius are what mark the stories as memorable. Very much in the tradition of Van Vogt and I’d say formative in the development of Orson Scott Card’s Ender stories. (In particular Tim’s literary life reminds me of Peter and Valentine Wiggin’s development in “Ender’s Game.”)

Isaac Asimov‘s “No Connection” (Astounding, June 1948) is a story of the bear-like beings who inherit the Earth. They have discovered fossils of monkey people, but cannot accept the correlation of those remains to the evidence of awesome destruction. It’s a poignant tale of what happens after the Bomb, in a world so removed from our own that the cataclysm itself is long-forgotten, let alone the fools who created it. The story reminds us that we are not in fact the pinnacle of anything and we ought to tread lightly. The reader should note that the story was written only a year or so after the Bomb was invented.

In fact, there are many Cold War and nuclear armageddon elements present in these stories, suggesting that the violent closure of WWII had people scared to death, and that many people anticipated the détente which would harden between the West and the communists. Too bad all these cautionary tales didn’t prevent the events that followed.

By far the oddest expression of these anxieties is in Robert Moore Williams‘ “Refuge for Tonight” (Blue Book, March 1949), a pre-Red Scare bit of paranoia. In lieu of a military invasion, the European block has decided to use germ warfare to weaken the US before taking it over by force. A motley group of cagey survivors makes its way to the Colorado Rockies, chasing a wild rumor that there’s a Bomb there which can be fired at the invader. What they find instead is the installation of a mad scientist who has secretly built a rocketship. After weaving their way through a firefight, the ragtag remnant climbs aboard for greener pastures under other suns.

By far the oddest expression of these anxieties is in Robert Moore Williams‘ “Refuge for Tonight” (Blue Book, March 1949), a pre-Red Scare bit of paranoia. In lieu of a military invasion, the European block has decided to use germ warfare to weaken the US before taking it over by force. A motley group of cagey survivors makes its way to the Colorado Rockies, chasing a wild rumor that there’s a Bomb there which can be fired at the invader. What they find instead is the installation of a mad scientist who has secretly built a rocketship. After weaving their way through a firefight, the ragtag remnant climbs aboard for greener pastures under other suns.

While I wouldn’t call this story, or the selections in this book in general, reactionary, there are some decidedly jingoistic, as well as culturally conservative elements throughout. Bradbury suggests reason without faith is a crock, Shiras excoriates atheists and non-believers, Williams casts doubt on the motivations of the Europeans (who at the time were deep in recovery from the devastation of their second continental war in three decades) in what is clearly an attempt to impugn the United Nations, Carr’s fable celebrates the obvious rectitude of American philosophy while denigrating the Enemy as beyond redemption, and most of the stories are of adventurous, bold men and docile, accomodating womenfolk. Even the uppity women in these stories know their place (or learn it).

Many of the remaining stories, all of them more explicitly sfnal than the preceeding examples, were published in Astounding. The relative dearth of material from Astounding in this volume, compared to the contents of the huge anthologies (Healy & McComas, and Groff Conklin’s four tomes) which appeared around the time this one did, but which covered slightly older material, suggests either a more catholic taste on the part of the current editors, or that perhaps Astounding‘s primacy in the field was ending even before F&SF and Galaxy made their appearance (1949 and 1950, respectively). Certainly developments in the real world increased general interest in science fiction, opening lucrative slots to able and willing writers. War’s end probably increased the number of aspirant hacks, as well. Though the pulp era was closing at this time, it wasn’t quite over yet. Teevee was a decade away from domination.

John R. Pierce’s (as by J. J. Coupling) “Period Piece” (Astounding, November 1948) is a short, intense vision of an Eloi future in which simulacra are constructed and implanted with the relevant memories and knowledge of various historical and geographical periods intended to provide amusement. Our hero is such an automaton, but he discovers his own artificiality too late, and the knowledge causes him to malfunction and commit suicide. The idea here being that the Gatsbyan rich of the future need diversions and entertainments commensurate with their vast intellects and technological prowess. It’s an empty and futile life, but when has life not been empty and futile? A Wellsian coda to Huxley’s Brave New World.

John R. Pierce’s (as by J. J. Coupling) “Period Piece” (Astounding, November 1948) is a short, intense vision of an Eloi future in which simulacra are constructed and implanted with the relevant memories and knowledge of various historical and geographical periods intended to provide amusement. Our hero is such an automaton, but he discovers his own artificiality too late, and the knowledge causes him to malfunction and commit suicide. The idea here being that the Gatsbyan rich of the future need diversions and entertainments commensurate with their vast intellects and technological prowess. It’s an empty and futile life, but when has life not been empty and futile? A Wellsian coda to Huxley’s Brave New World.

In Henry Kuttner‘s “Private Eye” (Astounding, January 1949), a man plans the perfect murder in another brave new world which possesses the technology to observe past events. The law has morphed around this disruptive technology by making intent subject to constitutional provisions guarding against self-incrimination. So the only evidence which is admissable is the recorded physical evidence. Intent to kill must be decided by a jury without recourse to the accused’s memory, in other words.

In Henry Kuttner‘s “Private Eye” (Astounding, January 1949), a man plans the perfect murder in another brave new world which possesses the technology to observe past events. The law has morphed around this disruptive technology by making intent subject to constitutional provisions guarding against self-incrimination. So the only evidence which is admissable is the recorded physical evidence. Intent to kill must be decided by a jury without recourse to the accused’s memory, in other words.

Our “hero” sets out on a long con and succeeds. He murders the man he hates and is acquitted. Unfortunately the object of his affections sneers at his claim to her that he has planned such a caper and murders her in righteous indignation, but this time he isn’t going to escape justice. Or will he? Did he intend to kill his beloved, or just snap? Only a jury of his peers can tell.

This is a swift, swirling story, the thrust of which is the way society incorporates new technologies. In this case, the time viewer makes hash of secrecy and privacy. How might we adapt to such a development? Kuttner provides a chilling and clever response. It also illustrates my earlier points about the differences between today’s fiction and yesterday’s. The motivations of the characters are clear, but simplistic. The action plays out on an almost bare stage, and are constrained by a telegraphic laconicism concerning the mise-en-scène. We are told just enough about this future to appreciate the plot, but not enough to immerse us in this future or make it seem real. That level of detail would build over the ensuing decades. Here the focus on the machinations of the plot suffices: different times, different values.

Another “long con” story with social implications (as well as some of the rudiments of Herbert’s later “Dune” series) is found in Poul Anderson‘s “Genius” (Astounding, December 1948). In the far future, a group of social scientists has established a set of planets with experimental subjects whose societies possess certain extraordinary traits under a variety of conditions. The group’s long-term plan is to produce a stasis-shattering population of supermen who will goad humanity to ever greater heights of accomplishment. Two men are on their way to visit a planet of exceptional people who have developed a high level of technology without a trace of aggression or violence: a brutish soldier skeptical of the genius colony and an academic with great hopes for the experiment. The scholar is determined to stop the military man at any cost; he believes the military man will destroy this astonishing fruit of breeding and planning. It turns out that the military man is a ringer, a native of the planet in question, on a mission to test the scholar’s commitment. The native geniuses are a step ahead of even the bright scientists. The question which lingers is: given enough time, and enough reiteration, can human beings produce a better variety of itself? In the past robots were seen as the answer, lately AIs. Anderson suggests mere human beings could fill that role, sifted like wheat berries, selected and carefully cross-bred.

In “Eternity Lost” by Clifford D. Simak (Astounding, July 1949), a method of extending life through rejuvenation is jealously guarded by the few who have been judged crucial to the ongoing project to achieve immortality, a prospect delayed solely by the availability of another planet to accommodate a species whose members never die. The ruthless senator who lies at the heart of this story is approaching his latest rejuvenation session, but is refused. Bitter, angry and vindictive, he makes plans to break all the laws he helped set in place to procure one more extension. He fails. Disconsolate, he publicly repudiates the process, embarrassing the haves. Unfortunately, in his senescent feebleness, he has failed to comprehend that he has been offered a chance at immortality on another world. Researchers have found a new planet to accept the immortals, but now the senator has lost his chance at the prize. The story has the feel of a machine rapture story.

In “Eternity Lost” by Clifford D. Simak (Astounding, July 1949), a method of extending life through rejuvenation is jealously guarded by the few who have been judged crucial to the ongoing project to achieve immortality, a prospect delayed solely by the availability of another planet to accommodate a species whose members never die. The ruthless senator who lies at the heart of this story is approaching his latest rejuvenation session, but is refused. Bitter, angry and vindictive, he makes plans to break all the laws he helped set in place to procure one more extension. He fails. Disconsolate, he publicly repudiates the process, embarrassing the haves. Unfortunately, in his senescent feebleness, he has failed to comprehend that he has been offered a chance at immortality on another world. Researchers have found a new planet to accept the immortals, but now the senator has lost his chance at the prize. The story has the feel of a machine rapture story.

Speaking of which, so many “new” story memes seem to follow from “old hat” memes. Immortality on another planet has evolved into consciousness-uploading to a computer, psionics has become cyberspace, robots become AIs, lost worlds have become alternate history.

Finally, two stories by the “dean of science fiction authors” hisownself. Will F. Jenkins (as Murray Leinster) in “The Strange Case of John Kingman” (Astounding, May 1948) tells the tale of a man in a mental institution…for centuries. He’s an odd man, always running a fever, with a curious, haughty mien, and a way with machine diagrams. He may turn out to hold the secrets to a fabulous future for humanity, if he can be convinced to reveal them. It turns out he’s a criminal from another world, a man whose sociopathy is so ingrained that his marvelous capacity for genius is inextricably woven into it. Curing him of his madness destroys his knowledge, rendering him useless to the powers-that-be. This gem of a tale is both a fable of the inherent peril of knowledge and technology, while at the same time a powerful and convincing psychological portrait of a being so at odds with the world around him that the only place he fits into is an alien madhouse.

Finally, two stories by the “dean of science fiction authors” hisownself. Will F. Jenkins (as Murray Leinster) in “The Strange Case of John Kingman” (Astounding, May 1948) tells the tale of a man in a mental institution…for centuries. He’s an odd man, always running a fever, with a curious, haughty mien, and a way with machine diagrams. He may turn out to hold the secrets to a fabulous future for humanity, if he can be convinced to reveal them. It turns out he’s a criminal from another world, a man whose sociopathy is so ingrained that his marvelous capacity for genius is inextricably woven into it. Curing him of his madness destroys his knowledge, rendering him useless to the powers-that-be. This gem of a tale is both a fable of the inherent peril of knowledge and technology, while at the same time a powerful and convincing psychological portrait of a being so at odds with the world around him that the only place he fits into is an alien madhouse.

Then there’s “Doomsday Deferred” (The Saturday Evening Post, September 24, 1949) which relates the story of a man uneasy with his own tale. In the rainforest of Brazil he has met an implacable enemy, a conscious being that could overrun the human world within a generation, a seething mass of drive, toil and indefatigable effort: ants. He defeats the colony he encounters, but he fears this victory will be short lived. He knows no one will believe his tale, but he must tell it just in case. A creepy sfnal take on an old and honored story form, this is a chilling story of a possibility that could still happen.

One interesting note about these Jenkins stories is they both meld the fable form and the mimetic, yet they were written by the oldest, most established writer of the bunch. Leinster/Jenkins was truly a master science fiction writer, incorporating the best of the halcyon days of story yore and anticipating the era of psychological naturalism to come.

The selections here seem preoccupied with the menace of human ingenuity and invention. There’s concern about who’s watching the watchers, and with who decides what is of value, and what is chaff. I’ve always maintained, and shall always maintain, that sf is a useful artform. In its purest form, it helps human beings relate to the modern condition: knowing our place in the cosmos, understanding at least the rudiments of how that cosmos works, and appreciating the human predicament, the interface between the mind and the body, between humans and their tools. Science fiction ponders issues considered esoteric by our pre-modern antecedents but which are inescapable now.

In these stories, that work of mediation is well and adequately carried out. There’s frolic and frivolity, but there’s engagement with the new world aborning too. Perhaps these stories made the succeeding decades easier for some to endure. I think the decisive mark of the value of these choices made over half a century ago is how relevant some of them still are, even after all those changes and disruptions.

Good old science fiction. Of any vintage.