“Isolate” by Tom R. Pike

“The Robot and the Winding Woods” by Brenda Cooper

“Outside the Robles Line” by Raymund Eich

“Retail is Dying” by David Lee Zweifler and Ronan Zweifler

“Groundling” by Shane Tourtellotte

“Amtech Deep Sea Institute Thanks You for Your Donation” by Kelsey Hutton

“North American Union v. Exergy-Petroline Corporation” by Tiffany Fritz

“Short Selling the Statistical Life” by C. H. Irons

“Momentum Exchange” by Nikolai Lofving Hersfeldt

“And so Greenpeace Invented the Death Ray . . .” by C. Stuart Hardwick

“Mnemonomie” by Mark W. Tiedemann

“Methods of Remediation in Nearshore Ecologies” by Joanne Rixon

“The New Shape of Care” by Lynne Sargent

“First Contact, Already Seen” by Howard V. Hendrix

“The Scientist’s Book of the Dead” by Gregor Hartmann

“Siegfried Howls Against the Void” by Erik Johnson

“The Iceberg” by Michael Capobianco

“Interconnections and Porous Boundaries” by Lance Robinson

“Bluebeard’s Womb” by M. G. Wills

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

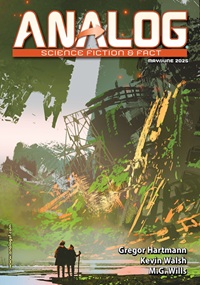

A single novella, four novelettes, and fourteen short stories appear in this issue.

“Isolate” by Tom R. Pike takes place in a galactic empire ruled by a monarch who is worshipped as a deity. The protagonist is a cleric and a linguist, sent to a remote region of a planet recently annexed to the empire. Her task is to determine if the local language is related to the empire’s official language, and thus acceptable, or if it must be eliminated.

Although the empire is clearly an authoritarian one, the relationship between its representatives and the locals is more complex than simply that of oppressor and oppressed. The characters are also realistically multifaceted, one in particular acting as both ally and antagonist to the main character. The method by which the protagonist studies the local language is believable, and the theme of depriving people of their native tongue is one that resonates with events in the real world.

In “The Robot and the Winding Woods” by Brenda Cooper, an elderly couple maintains a campground, even though there have been no visitors for many years. A robot arrives to tell them that the area is to be returned to pure wilderness, and that they must leave. Another fact revealed by the robot changes the situation.

This is a quietly emotional tale that avoids sentimentality. The robot is as fully developed a character as the humans, while remaining true to its nature as a machine. The author displays respect for both people and nature, offering a balance between the two.

“Outside the Robles Line” by Raymund Eich takes place in the asteroid belt, which has been settled for many centuries. A young man from one of many space colonies arrives and gives a council of elders a new plan to supply energy. In turn, they provide a deeper look at the situation, and offer the fellow advice about his future.

The story has a great deal of technical detail, even requiring two graphs. This tends to distract from the theme of a young person receiving wisdom from elders. The detailed background of inhabited asteroids and orbiting space colonies is more interesting than the plot.

In “Retail is Dying” by David Lee Zweifler and Ronan Zweifler, an elderly man pays a visit to a shopping mall that is mostly empty. An encounter with a man offering a dog for adoption changes his reason for being there.

I have deliberately avoided giving away too much about the story and its speculative content, which is subtle but of vital importance to the theme. Suffice to say that this deceptively lowkey tale has a powerful effect.

The main character in “Groundling” by Shane Tourtellotte is a member of the crew of a starship who remains aboard the vessel while others leave to become colonists on the planet it orbits. Those who normally stay on the starship, as he does, consider temporary duty on the planet to be an unpleasant assignment. The protagonist has a different attitude.

The way the author explores the psychology of people born on a colony ship is interesting, even if I found it difficult to believe that most of them would lack even the slightest desire to visit the planet. Otherwise, this is a story with a very simple plot.

“Amtech Deep Sea Institute Thanks You for Your Donation” by Kelsey Hutton is a brief tale told from the point of view of a squid. It becomes clear why the animal has more knowledge than it should.

The astute reader will be able to predict what’s going on from the start. This may not be much of a problem in a story less than two pages long. The main appeal of this tiny work is its vivid descriptions of the deep-sea environment and its inhabitants.

As its title implies, “North American Union v. Exergy-Petroline Corporation” by Tiffany Fritz takes the form of the record of a court case, complete with copious footnotes. The situation involves an environmental disaster and whether the company named in the title should be held responsible for it.

The story’s format makes for dry reading, despite the fact that it involves a dramatic event. The intent appears to be a satiric look at the way corporations avoid punishment for misdeeds. Readers should be aware that much of this theme is revealed in the footnotes.

“Short Selling the Statistical Life” by C. H. Irons takes place at a time in the near future when the value of a human life (e.g. the amount of money that society will spend to preserve a person’s existence) is treated as a commodity, to be bought and sold on the stock market. Vignettes reveal how people secretly lower the market value of this abstract commodity in order to have those working to save lives profit from short selling, thus obtaining funds to continue their efforts.

If the above synopsis is confusing, this may be because my understanding of economics is minimal. Readers as ignorant as I am about the stock market are likely to find the premise difficult to understand. Even so, one has to wonder if making the market value go up would be a more direct way of helping people rather than making use of short selling.

The two main characters in “Momentum Exchange” by Nikolai Lofving Hersfeldt have been on a planet occupied by genetically created versions of pre-Homo sapiens humans for thousands of years. As the society of the created humans progresses technologically, the woman tries to escape from the planet while the man prevents her from leaving.

I found this story’s plot and background very hard to understand. I never knew why the pair was on the planet or why the woman wanted to escape. I failed to grasp the significance of the notebook the woman carries through millennia, or why the two enemies are also lovers. If the author’s intent is to create a strange future, this is successful. If it is to tell a coherent story, this is not as effective.

In “And so Greenpeace Invented the Death Ray . . .” by C. Stuart Hardwick, an unknown group takes control of satellites intended to beam energy down to Earth, redirecting their orientations so they might be used as weapons. The protagonist and her fellow astronauts head into space in order to correct the situation at the risk of their lives.

Before the plot begins, there is a great deal of exposition about the way in which the satellites work. The actual struggle to fix the problem also involves much technical discussion. Those who are greatly interested in technological details will best appreciate this example of hard science fiction.

“Mnemonomie” by Mark W. Tiedemann takes place in a society where boys become men by having their memories completely replaced, instantly changing them from adolescents interested in aggressive sports to adults with careers. One such young man suffers brain injury during an attack by a rival team, so the process is not completely successful, leaving him with memories of his past. In this way, he learns something about the world in which he lives.

The premise is certainly original and is narrated in a way that leaves the reader as disoriented as the protagonist. The fact that the process is only used on men and that women are in control of it raises many questions. Perhaps the author is saying something about the different ways in which girls and boys develop into adults. Be that as it may, the story is intriguing but opaque.

“Methods of Remediation in Nearshore Ecologies” by Joanne Rixon features a woman measuring pollutants in water in a future world where rising sea levels have flooded buildings, thus releasing toxins. With the help of a minimally sentient artificial intelligence, she plans how to deal with the problem by using microorganisms to remove the pollutants.

This is a slice of life, with little plot other than the basic premise. The fact that the woman gathers shells in order to make them into art adds characterization, also provided by the relationship between the woman and her sister. This makes for pleasant, if unexciting, reading.

In “The New Shape of Care” by Lynne Sargent, an elderly woman in hospice is cared for by a robot. She thinks back on the ways in which relatives and robots cared for other members of her family.

Less than two pages long, this brief tale depends on its final scene for its full impact. The way the woman reacts to the simultaneous presence of her adult daughter and the robot is unexpected, and offers insight into the nature of caretaking.

“First Contact, Already Seen” by Howard V. Hendrix offers brief scenes, from prehistory to historical times to the future, of people exterminating others whom they consider to be less than human. The lesson offered here, in less than two pages of text, is an undeniable one, if sadly obvious.

“The Scientist’s Book of the Dead” by Gregor Hartmann takes place years after a devastating war wiped out most of humanity and a revolution resulted in a world ruled by technocrats. The western hemisphere is completely depopulated and left as a wilderness area.

The aging leader of the revolution and his chief of staff, a young woman bred to be at the peak of human ability, lead the narrator and other technocrats on a hike in an otherwise deserted North America. The intent is for the woman to present her plan to sterilize all but the most genetically superior people, resulting in an even smaller human population but one that will be greatly superior. The narrator argues against the plan, and the leader makes his decision.

This lengthy synopsis conveys the fact that the story has a complex background that is directly relevant to the plot. The nearly superhuman woman is not simply an antagonist, but a character with depth. Her argument for preventing ninety percent of humanity from breeding is, from her point of view, logical and beneficent. The narrator is just as sincere in his objections, and the leader considers both opinions carefully. The story offers much food for thought, without easy answers.

The two characters in “Siegfried Howls Against the Void” by Erik Johnson are sentient starships, many lightyears apart in their separate voyages. Over millennia, they send occasional messages to each other. One of them, identified as male, comes to depend on the signals from the other, identified as female.

In addition to making the starships seem like people, the author also anthropomorphizes stars and planets, describing them as mothers and their children. Despite having no human characters, this is a romantic story, with interstellar exploration as a source of emotional wonder and despair. Thus, it may be churlish to question why starships without crew are being sent on these voyages, the female vessel even going into a wormhole in order to explore another universe. This is the author’s first published story, and it reveals a rich imagination and a lush narrative style that could benefit from a little discipline.

In “The Iceberg” by Michael Capobianco, a man is left stranded on a vast piece of Antarctic ice after global warming causes massive flooding of the frozen continent. To make matters worse, failure of all communication satellites makes it impossible for him to signal for help.

There are no surprises in the plot, given the man’s hopeless situation. The simultaneous melting of the Antarctic ice and the sudden loss of communication seem like almost unbelievably bad luck, as there is no apparent connection between the two disasters. The story is notable mostly for its vivid descriptions of the environment.

“Interconnections and Porous Boundaries” by Lance Robinson takes place on an asteroid inhabited by American colonists who mine the giant rock for rare elements. A lack of a trace mineral in their diet threatens the lives of the inhabitants, and realities of space travel make it necessary to wait for more than a year for supplies from Earth. Attempts to fix the situation lead to further complications.

Adding to the problems are tensions between nations on Earth that could lead to war. When a nearby Chinese asteroid colony is decimated by a disaster, the chief of operations, already facing multiple challenges, has to decide whether to risk an international incident to help.

As can be seen, there is plenty of plot in this fast-paced yarn. The theme of all systems, from ecological to technological to political, involving complicated relationships among multiple factors is made clear from the start. It is evident from the title all the way to the very last word. Maybe a little too much goes wrong to be fully plausible, and perhaps the conclusion involves an equally unlikely stroke of good luck, but readers are likely to overlook these quibbles.

The novella “Bluebeard’s Womb” by M. G. Wills deals with a project to create a uterus within a man’s body, which can then have an embryo implanted in it so the man can give birth by Caesarean section. The first volunteer is an acquaintance of the woman in charge. He has his own agenda, which only becomes clear after the child is born.

Although this is not the first story to feature male pregnancy, it is an unusually realistic and scientifically plausible version of the theme. The story has a strong feminist viewpoint, evidenced by the fact that the intent of the project is to fight misogyny by giving men the experience of childbirth. This is supposed to eliminate their envy of women’s ability to bring life into the world, thus reducing their fear and hatred of females.

There is also a bizarre subplot, in which the woman in charge of the project has visions of the radical feminist Shulamith Firestone, said to be the woman’s grandmother. (In real life, Firestone is not known to have had any children.) Some of Firestone’s works advocated for reproductive technology that would free women from pregnancy, so the story can be seen as an extrapolation of her speculation. (The story also features another project, which produces artificial wombs.)

The pregnant man’s behavior is highly irrational, making him an implausible antagonist. The story also features an entirely admirable male character, so this is unlikely to be due to misandry. In any case, this provocative work is sure to create controversy. Readers’ opinions on the issues raised in it will determine how they react to it.

Victoria Silverwolf has never been pregnant.

Analog

Analog