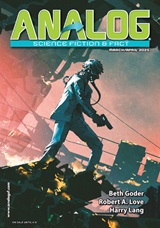

“Murder on the Eris Express” by Beth Goder

“NOT Optimus Prime” by Lorraine Alden

“It Eats Metal” by Mark Ferguson

“To Reap, To Sow” by Lyndsey Croal

“The Emergency Contact” by Arendse Lund

“Those Other Replicator Manufacturers are Ripping You Off” by Jon Lasser

“Track Eats Track” by Avi Burton

“Concerning the Multiplicity of Children in Central Florida’s Suburbanized Wetlands” by Ichabod Cassius Kilroy

“Mr Palomar Goes to Space” by Hayden Trenholm

“The Code of His Life” by Owen Leddy

“Echo, Write To All” by Nate Givens

“The Timecop and the Timesocial-Worker” by S.L. Harris

“In Her Element” by M.T. Reiten

“If the Weather Holds” by Marissa Lingen

“Murder with Soft Words” by Mike Duncan

“In the Hole” by John Markley

“Heat Death” by Kate MacLeod

“The Return of Tom Dillon” by Harry Lang

Reviewed by Mike Bickerdike

“Murder on the Eris Express” by Beth Goder is an entertaining novella; a ‘whodunnit’ murder mystery set on a spaceship. It’s written in a light-hearted, comedic tone, yet maintains a serious plot thread throughout. With only four humans on board, an AI entity who manages the ship, and two cleaning bots, the possible suspects of the murder are not many, though the truth is well hidden by the author until the end. In this way, it’s quite a successful murder mystery, following the accepted rules of such literature. If it falls down in any regard, it is perhaps in its speculative SF elements. One issue here lies in the apparently inconsistent capabilities of the AI entity ‘Mo’ (essentially a self-aware computer). Upon boot-up at ‘birth’ she downloaded a million lives worth of books and movies in only a few minutes but then in the story she takes over a minute to check her memory for some dialogue in the recent past. This illustrates a problem with having computer AIs provide the readers’ point of view: they have to think and act at the same speed as the reader in order to provide an internal dialogue that resonates, when we know they can actually think and act millions of times faster than we do. This has the potential to create a disconnect in the internal logic of the story, which occurs on a few occasions here. That said, it is an enjoyable tale, and if you’re happy to suspend disbelief about the shifting capabilities of the protagonist AI, it should provide good entertainment.

“NOT Optimus Prime” by Lorraine Alden is an interesting and inventive short SF story. A young university researcher is searching for large prime numbers, using a quantum computer. Her efforts attract unexpected attention, as well as leading to an entanglement with a university cleaner. By providing both a significant, distant threat, as well as close physical threat, the author cleverly blends a source of SF tension and intrigue, with a situation offering immediate peril. In this way, the story maintains interest and excitement, while also delivering a satisfying SF idea. Recommended.

“It Eats Metal” by Mark Ferguson is another good SF story, though it perhaps offers less novelty than the preceding tale. This is essentially SF horror, telling the tale of something living in the disused swamp at the edge of a town. While this doesn’t sound especially novel, the tale is well-paced and well-written, with an appealing set of characters. And while we can guess pretty much where the tale is going, it manages to keep us guessing enough to make it an enjoyable read.

“To Reap, To Sow” by Lyndsey Croal is not such a successful piece. A researcher is trying to optimise the growth of tomatoes through the use of nanotechnology at a facility in the highlands of Scotland. The tension here is supposed to lie in her challenges in achieving success, and the consequences of her not owning her research such that she cannot do what she wants with it. A couple of things let the tale down; on the one hand, the critical need for her work is never explained, so we have little reason to root for her; secondly, the use of nanotechnology bots within the fruit to act at an epigenetic level sounds unlikely (why not use modern molecular biology techniques—nanotech sounds like a daft approach); and thirdly, of course the research would belong to her employers who pay her salary—that’s how all corporate research the world-over works, and always will do.

“The Emergency Contact” by Arendse Lund is a very short story, with a jokey premise. An elderly woman is stranded in her house after a storm and calls emergency services. However, having called the wrong number, her approach for help is far from what she expected. This sort of SF idea has been seen many times in the past, and there is little here to raise it above the average.

“Those Other Replicator Manufacturers are Ripping You Off” by Jon Lasser is written in the style of an infomercial, with an ironic approach. The format enables the author to take a swing at both advertising and the morally weak nature of the target customers. It’s quite readable, but without a plot the joke and cynicism struggle to provide enough interest on their own.

“Track Eats Track” by Avi Burton gets the magazine back to story-telling, but it’s only partially successful. A SenTrack driver is grieving the loss of a fellow driver. He doesn’t believe the other driver died naturally and wishes to quit racing. The prose is fine, and characterisation isn’t bad, but the exact nature of the ‘SenTrack’ (with its ever-shifting asphalt) is not well explained. Is it purely a virtual reality sport, or is there a real element to the racing? How do the fans watch it if it’s virtual? It’s far from clear what the sport is, we cannot really picture it, and accordingly it ultimately fails to convince as a story.

“Concerning the Multiplicity of Children in Central Florida’s Suburbanized Wetlands” by Ichabod Cassius Kilroy is rather an odd short story. It reads like a fantasy, not SF, with the ‘ghosts’ of children representing (presumably) alternative reality pasts and futures. Perhaps the story presents an idea of how a multiverse of all possible outcomes would look like if we could see the outcomes that didn’t happen, as ghosts. Unfortunately, the idea is not very clearly expressed, there is not much plot, and we are given little reason to care what happens to any characters, for whom there is no jeopardy or dramatic tension.

“Mr Palomar Goes to Space” by Hayden Trenholm is quite a brightly written SF story, somewhat in the vein of a Heinlein tale in which someone unwittingly goes into space. The set up promises much, with a fresh, jokey approach and some anticipation for what might transpire. Unfortunately, what eventuates isn’t especially novel and doesn’t quite satisfy our initial expectations.

“The Code of His Life” by Owen Leddy is a dystopian SF novelette, in which underground biotech provides a black-market economy for disenfranchised ‘biohackers’. This is a well-written tale, with well-developed characters and good pacing. Essentially a bio-thriller, the tensions are kept high throughout, and the biotechnology details are plausibly presented. It is often the case that biotech-based SF misses the mark when it comes to extrapolating current science to an SF setting, but here the author has done an admirable job bringing verisimilitude to the tale. Satisfying to the end, this story is recommended reading.

“Echo, Write to All” by Nate Givens is an intriguing SF short story, set on a colony world where the colonists have forgotten their origins. Having lost their scientific understanding of space travel and computation, they retain the vestiges of their knowledge by religious rites. One acolyte is asked to sacrifice themself for the Wardens, but can he turn the tables on the ‘assessors’? The plot exploits the use of computer code, which the acolytes learn by rote. This works well, though readers who are not software engineers will doubtless miss some of the details (I’m sure I did).

“The Timecop and the Timesocial-Worker” by S. L. Harris is a very short piece, set in a world where time travel is quite commonplace, and time cops correct errors in the timeline. The protagonist is a temporal social-worker and seeks to help a grieving widow. The idea is quite nice, but the story is too short to explore the idea properly, and there’s not much here to get excited about.

“In Her Element” by M. T. Reiten is flash fiction. Engineers are working on a ‘gleaner’ prototype—a machine that will break down any material to its constituent elements. There’s a twist of sorts at the end, but as a story it is rather weak, and too short to develop any tension or dramatic depth.

“If the Weather Holds” by Marissa Lingen is not described as flash fiction, though it’s exactly the same length as the preceding piece. This serves as a polemic against those who are laissez-faire about climate-change. There’s not much to it from a plot or character standpoint.

“Murder with Soft Words” by Mike Duncan strives to be literary, employing an off-hand and erudite style, and it generally well-written, but it lacks sufficient clarity to be really enjoyable. In a war between colonists of the Galilean moons of Jupiter, one naval officer on Callisto makes a bet with another officer that a comet will crash into Io, ending the war. The outcome and the reasons for it are clouded in obscurity. Asimov’s sage advice to be clear in one’s writing above all else, would be advice worth following by many modern authors.

“In the Hole” by John Markley is quite a well-told story, in which the protagonist tries to cheat a poker game using high-tech detection of special cards, in order to pay off huge debts. Tension is well managed here, and the characters have reasonable depth, though we don’t especially warm to the narrating character.

“Heat Death” by Kate MacLeod is an entertaining and well-written SF murder-mystery novelette. In the future, temperatures in Texas reach dangerously high levels, and in the scrub and hills of the state a man is found dead, apparently of heat stroke and dehydration. But how did he get here, and is his death more suspicious than it looks? The main characters are quite well rounded, and we are left guessing for some time as to what occurred, which makes for quite an engrossing read. If it lets down in any way, it’s that the conclusion does not fully satisfy—the rationale for the death doesn’t draw upon the reader’s sympathies, giving it rather a downbeat ending.

“The Return of Tom Dillon” by Harry Lang is a novella set on Mars and continues the murder-mystery theme of the prior story. A series of murders have taken place on Mars, carried out by a revolutionary group. When a new grisly murder occurs, referencing the revolutionary murders, it looks like the perpetrator may actually be a different individual. The story’s protagonist, a hard-drinking Martian cop, will bend any rule to get to the bottom of the case. This is written with more than a nod toward the hard-boiled detective fiction of Philip Marlowe or Sam Spade, though it doesn’t have the stylised patois of the gumshoe novels. The tale is engaging and it’s a crisply written tale. The advantage of a novella over much shorter work is that it has room to let the story breathe and develop—Mars here is painted with good depth and provides and interesting and realistic backdrop. Most readers should enjoy this story.

More of Mike Bickerdike’s reviews and thoughts on science-fiction can be found at https://starfarersf.nicepage.io/

Analog

Analog