“Walking on the Moon”

“Free Beer and the William Casey Society”

“The Return of Weird Frank”

“Sugar’s Blues”

“The Flying Triangle”

“The Zoo Team”

“Live from the Mars Hotel”

“The War Memorial”

“Moreau2“

“The Great Galactic Ghoul”

“The Emperor of Mars”

“Zwarte Piet’s Tale”

“The Weight”

“Kronos”

“The Death of Captain Future”

“The Exile of Evening Star”

“0.0G Sex: A User’s Guide”

“Working for Mister Chicago”

“High Roller”

“Shepherd Moon”

Reviewed by Richard E.D. Jones

Read books and short stories long enough, and, if you’re very, very lucky, you’ll find that one author. That one author will be a writer who changes the way you look at your favorite genre. For me, that author is Allen Steele.

Having grown up on a steady diet of galactic empires, amazing spaceships powering through a populated universe at exponentials of light speed, powered by pure gee-golly-wizz reading Steele’s early fiction, his Near Space stories were like a full-body splash of ice water: a shock, leading to invigorating new thrills and chills.

Steele’s Near Space stories haphazardly form a future history of mankind’s first furtive, staggering moves off Earth and out into the wider solar system. Filled with flawed men and women who were motivated by easily understandable drives – money, freedom, love, survival – the stories took a more realistic look at what living and working in space might look like.

In Steele’s stories, it’s not the brave and daring space commander who overcomes the nasty xenomorph and saves the day. No, it’s the burnt-out, Grateful Dead-loving, working slob who finds a way to survive a solar flare while he’s helping to build the first large-scale space habitat in Earth orbit who takes center stage.

It’s like the Capt. Kirk line from the fourth Star Trek movie: “I’m from Iowa. I only work in space.” That sentiment could apply to a great number of Steele characters slinking along the spaceways, cadging a drink wherever they can.

As with any writing project that takes place over almost twenty years, there are a number of inconsistencies and continuity gaffs to be found when you read all these stories in a short span. Don’t let it bother you. Just chalk it up to non-reliable narrators and move on. These stories are too good to get anchored in the gravity well of picked nits.

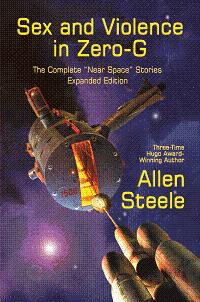

This is the second edition of Sex and Violence in Zero-G, the first published in 1998. Since the publication of the original, Steele has gone on to write five more short stories in the Near Space series – “Moreau2,” “The Great Galactic Ghoul,” “Zwarte Piet’s Tale,” “The Emperor of Mars,” and “The Zoo Team” – and they are included in this volume, along with a new introduction by the author.

Having all these stories in collected form also showed me something I’d apparently been missing when I read Steele’s short fiction earlier. Most of these stories have a passive point of view. That is, the story is being related by someone who wasn’t the prime mover of the incident being shown.

For instance, the Diamondback Jack stories (set in a bar located near the Kennedy Space Center) are told by a reporter. He’ll go into the bar, see or meet someone interesting and then tell the story as related to him.

I’d say a majority of the stories are told in this manner. Mostly this sort of thing works. I mean, not all stories can be told by or from the viewpoint of the hero. Sometimes a little distance is a good thing, to give us perspective on what happened. It’s just that having Steele use the same device again and again has a bit of a distancing effect as I continued reading deeper into the collection.

Which leads me to my first suggestion regarding this book: Take a while to read it. Read a couple of stories and then put the book away for a while. Mind you, I’m not saying the point of view diminished my enjoyment, but it did begin to seem a bit overly familiar.

No Near Space book would be complete without the inclusion of “The Death of Captain Future,” which won the Hugo award in 1995 for best novella, and “The Emperor of Mars,” which won the Hugo for best novelette in 2010.

“The Death of Captain Future” is, I think, the more interesting of the two. In it, Steele compares the differences between the future of space travel to be found in the early SF pulps with what could be considered the more realistic depiction of space flight found in his, and other’s, stories published nearer to today.

Capt. Future is a fat, delusional slob who thinks he’s a pulp-era space hero and insists that others treat him as such. Once again, the story is told from the point of view of someone seeing the action from outside, although this protagonist does get in on the action as the story progresses. Through arrogance and stupidity, Capt. Future accidentally damns himself, but manages to save thousands of lives.

“The Emperor of Mars” continues Steele’s tradition of having a narrator outside the story who relates what happened, giving the story a rather clinical feel. In this story, a worker in a beginning Aresian colony mourns the death of his sweetie and his family back on Earth in a unique way.

Both of the stories are, as always with Steele, well written. Which is good for the reader, as “The Emperor of Mars” is more of an anecdote than a story. But it’s still one humdinger of a great anecdote. This is the sort of anecdote that would get you free drinks in any bar for as long as you desired.

That’s the thing about Steele’s stories. These characters feel like real people, not the cardboard cut outs or thinly disguised, walking philosophical viewpoints of some authors.

That feel is critically important, especially in an environment that’s literally out of this world. Steele’s stories strive for a welcome verisimilitude, and how things might work in an environment that actively works against that sort of thing. And it works. Put ordinary people into a harsh, hostile environment, do bad things to them and then watch how they deal with it. It’s a winning combination, especially as written by Allen Steele.

In looking back over my notes for these stories, I realized that I spent most of them recording little things that bugged me. But I want to be very clear on this: Those little things? They don’t mean a thing. Seriously, I had a ball (re)reading these stories. Steele paints a hard-edged picture of life in an unforgiving environment, and how people who seem distinctly lifelike still manage to eke out a living, some finding peace and some finding love, but all of them finding a place to belong.

These are good stories.

Which leads to my second recommendation for this book: Go buy it right now. Buy it and read it and enjoy it.

I give this book my highest recommendation. I can’t stress this strongly enough: These stories are the good stuff. Go and read. You will be glad you did.