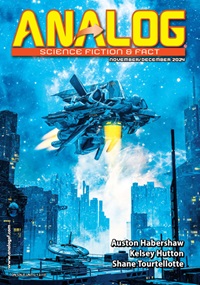

Analog, November/December 2024

Analog, November/December 2024

“That Far, Uncharted Ocean” by Auston Habershaw

“Lady Ballistic: Fast and Accurate Cleaning” by Alexander Jablokov

“Mirrorstar” by Sean McMullen

“Hell Five” by Arlan Andrews, Sr.

“Emergency Calls Only” by Kelsey Hutton

“Galilean Crossing” by Pauline Barmby

“Death of an Intelligence” by Mjke Wood

“If This Flesh Were Thought” by Matt McHugh

“A Short Future History of Whales” by Jenny Williams

“In Your Dreams” by Jerry Oltion

“Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc” by Mary Soon Lee

“A Garden in the Sky” by William Paul Jones

“The New Saharan Energy Company, Annual Report 2058” by David McGillveray

“The Touchstone of Ouroboros” by David Cleden

“The Outsiders” by Shane Tourtellotte

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

Fifteen new works of fiction appear in this issue, including a single novella and a quartet of novelettes.

The novelette “That Far, Uncharted Ocean” by Auston Habershaw opens the issue. The narrator is selected by snail-like aliens to help them win a sailing race on a watery planet, involving multiple species, that lasts for centuries and involves deadly combat among the contestants.

The author does a fine job detailing the culture shock experienced by the narrator. The way in which he uses his expertise in sailing, while dealing with aliens who have no experience with large bodies of water, is often witty, without descending into farce. The story will particularly appeal to readers interested in the sport of sailing.

The protagonist of “Lady Ballistic: Fast and Accurate Cleaning” by Alexander Jablokov makes a living by removing infestations from other universes. Her current assignment involves removing huge spider webs from a house about to be sold. Complicating matters is the arrival of hordes of bees that pose a threat to humanity.

This quirky tale has a premise that isn’t quite comic, but definitely tongue-in-cheek. The way in which the bees and spiders interact is imaginative, even if it does require a large amount of suspension of disbelief.

The title of the novelette “Mirrorstar” by Sean McMullen refers to a pair of enormous telescopes deep in space, perpendicular to the solar system. Their extreme isolation and the vast distance between the two facilities allows them to act like a single telescope the size of the solar system.

The narrator investigates the bizarre case of a woman frozen solid at the focus of one of the telescopes, her naked body covered with thick fur. This weird transformation is just a hint of the extraordinary discoveries that follow.

The premise described in the opening paragraph above is more interesting and plausible than the later revelations, which strain credibility, even if they are highly original. The telescope far above the solar system reminds me of Joan D. Vinge’s frequently reprinted 1978 story “View from a Height,” and I wish more had been done with that idea.

“Hell Five” by Arlan Andrews, Sr. features a boy who barely stays alive by stealing technology from the wealthy and selling it to a fence. With the help of the fence and a fellow street urchin, he faces an unexpected future.

The story has the slangy, hardboiled style of cyberpunk, which will seem familiar to many. The final two words add an interesting twist, which astute readers may be able to predict from the title.

“Emergency Calls Only” by Kelsey Hutton takes the form of a message from a woman about to fall into a black hole to an estranged lover. This fairly brief tale has emotional appeal. The woman’s lover happens to be an alien, although this is irrelevant to the plot.

Only two pages long, “Galilean Crossing” by Pauline Barmby describes how the protagonist skates a vast distance from one base on the moon Europa to another, in order to carry bone marrow that will save the life of a leukemia patient. There’s little doubt that this desperate mission will be a success. This tiny tale is vividly written, but I question whether the use of second person narration adds anything.

In “Death of an Intelligence” by Mjke Wood, an historian, accompanied by a student, investigates the destruction of one of the powerful artificial intelligences that control the world, making it something of a utopia. Questioning of suspects leads to a surprising solution.

The story follows the format of classic detective fiction, with the narrator acting as an audience for the investigator’s brilliant deductions. It features the familiar climax of the detective gathering all the suspects together to announce the name of the culprit. Cleverly plotted, this whodunit will best appeal to fans of the genre. Others may find it a little dry.

“If This Flesh Were Thought” by Matt McHugh takes place at a time in the near future when severely disabled people can have their minds control robotic devices that are then sent into the outside world to perform various errands for their owners. A police officer investigates a murder committed via such a device. With the help of a lawyer representing the woman who owns the device, himself bedridden and using his own device to work with the officer, the crime is solved.

The speculative technology is interesting and plausible. The devices are not fully humanoid robots, but resemble metal stick figures, and are thus more realistic. In comparison with the previous story, also a whodunit, this one has more depth of character and emotional appeal. In particular, the lawyer is an intriguing character, witty and brightly optimistic despite his disability, as well as a highly skilled professional.

The novelette “A Short Future History of Whales” by Jenny Williams alternates sections of text told from the points of view of two characters. One is a scientist, pregnant from frozen sperm taken from her husband, who has been dead for a few years. The other is a naval officer, investigating what seems to be a minor error message received during the test of a sonar system controlled by an artificial intelligence. Together they discover the explanation for a mysterious sound that devastates ocean life.

Just from this synopsis the reason for the destructive sound may be obvious. The story is not as much concerned with this basic plot as with its two characters. The scientist’s interior monologues, directed at her unborn child, are the heart of the story. The sections dealing with the officer, which are often technical, seem colorless by comparison.

In “In Your Dreams” by Jerry Oltion, two survivors of a car crash have dreams of their lives in alternate realities. A dream researcher helps them learn how to share their dreams, and even communicate with their other selves.

The premise is intriguing, if somewhat mystical and implausible. It leads to a philosophical conclusion very similar to that which appears in Larry Niven’s famous 1968 story “All the Myriad Ways.” Namely, the knowledge that all possible universes exist renders decision-making meaningless, so that people will do things they would not normally choose to do, reasoning that every possible action must take place in some reality. I found this conclusion questionable when I first encountered it, and I still do.

Only half a page long, “Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc” by Mary Soon Lee describes how superstitious Martian colonists rely on signals from cat behavior to determine how their construction projects should proceed. There is not much to this miniscule bit of whimsy other than the premise, which should please ailurophiles.

“A Garden in the Sky” by William Paul Jones takes place in a habitat floating in the upper atmosphere of Venus. The protagonist is in charge of a large collection of plants, genetically altered to survive in this environment, that grow on a platform hanging down from the habitat. A crisis causes her to be trapped outside of the habitat. When a severe storm approaches, she has to figure out a way to get back inside to survive.

As may be evident, this is a problem-solving story, of the kind often found in Analog. In typical fashion, the resourceful protagonist suffers many setbacks, but triumphs through a combination of courage and intelligence. There is nothing new about the basic plot, and this is a decent example of the form.

As its title implies, “The New Saharan Energy Company, Annual Report 2058” by David McGillveray takes place at a time when much of the Sahara is filled with solar panels. The protagonist wanders through the desert with his goats. He inadvertently comes across the scene of a bloody battle, and receives an object containing vital information from a dying woman. Dangerous encounters with the brutal security forces of the energy company follow, then an announcement that will change the world.

This short story has the richly imagined setting and thematic complexity of a full novella. The main character is an ordinary fellow who finds himself in a difficult situation, and proves worthy of the challenge. The notion that a benign project to supply clean energy could be corrupted by the greed of those in charge of it is a worthy theme, and the author makes use of it in a mature and sophisticated fashion.

In the novelette “The Touchstone of Ouroboros” by David Cleden, a religious cult worships an ancient alien object. Pilgrims come to touch the thing. If they stay in contact with it for too long, it absorbs them. The main plot deals with a cleric, who is losing his faith, and his superior, who plans to perform a seeming miracle in order to retain his position. Subplots involve the cleric’s confessor and a scientist who wants to study the strange object.

Although some of the mysteries surrounding the object are explained by the end, it remains an enigma. In a sense, it is also a character, albeit one that is impossible to comprehend. The story has a dark mood throughout that may not please all readers.

The novella “The Outsiders,” part of a series by Shane Tourtellotte, concludes the issue. Previous stories related how an alien society was devastated by an induced plague, how they recovered over a long period of time, and how they discovered an object that allowed them to track down its source. In this story, their descendants travel to a human colony planet, thought to be the source of the plague. Tense interactions between alien and human eventually reveal the truth.

Despite a dramatic plot, in which the aliens must decide if the humans were responsible for the disaster and, if so, how they should be punished, this is a rather leisurely story. Much of the text deals with the repressive government of the human colony world, and with the interactions among the various crew members aboard a trio of alien starships. (One enjoyable aspect of the story is that the aliens are not all alike, but come from various nations on their native planet, and have different languages and cultures.) I had to wonder if any species would actively seek justice, even for the most destructive act of genocide, after more than a thousand years.

Victoria Silverwolf is an ailurophile.