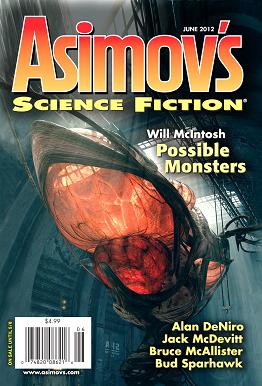

Asimov’s, June 2012

Asimov’s, June 2012

“Waiting At The Altar” by Jack McDevitt

“Final Exam” by Megan Arkenberg

“The Flowering Ape” by Alan DeNiro

“Free Range” by Bruce McAllister

“Missionaries” by Mercurio D. Riviera

“Possible Monsters” by Will McIntosh

“Scout” by Bud Sparhawk

“The Widdershins Clock” by Kali Wallace

Reviewed by Daniel Woods

“Waiting At The Altar” by Jack McDevitt

Warning klaxons, the hiss of air through vents, and the reeling of an unsteady ship greet Priscilla Hutchins as she is jolted into waking: the Copperhead has fallen out of FTL flight, and all eyes look to her for what to do next. It is an exam after all. When Hutch scans the surrounding space for danger and picks up an old style distress signal, the choice to go off-mission and investigate is all hers.

McDevitt’s piece is two stories in one. While ostensibly an account of Hutch’s first taste of command, it also tells the tale of Dave Simmons, the ill-fated space adventurer, and throws in a few aliens for good measure. McDevitt does a decent job of splicing these plots together, but the piece lacks an overall sense of peril or excitement. Even the dramatic opening becomes bland, because Hutch’s danger is an exam simulation, and she knows there’s no need to panic. A wan conclusion, an overly-familiar setup of “jump technology” and AI computers, and some rather underdeveloped aliens (“big black ship” is about all the info we get), make this a casual read only. It’s a shame too, because there is real poignancy in the tale of Dave Simmons. Unfortunately, his story (particularly his interaction with the aliens) is skimmed over, and told from too far a distance for me to feel it.

“Final Exam” by Megan Arkenberg

The slow death of a relationship is a difficult thing. Even the tiniest action – a tilt of the head when your partner leans in for a last kiss – can prove haunting and fatal, so when terror grips the world, what chance do two faltering people have? In “Final Exam” Megan Arkenberg tells the story of a life that is forever changed by the shambling things from the water.

This is an excellent piece, written in the style of a multiple choice exam paper (though whether it is an end of marriage exam, or an end of life exam, is left unnervingly vague). The questions are written with a cruel sneer by some awful narrator, and addressed directly to “you”. In just a few words, you’ll find yourself needing to know why “your marriage” failed, what happened to your ex-husband, and where the invading creatures came from. Indeed, your insecurity is picked out in merciless detail by constant references to people that are “skinnier than you,” and the effect is quite powerful.

Arkenberg’s narrative works because it taps into the nuanced, multi-faceted way we perceive and remember things. With each set of answers, a subject is broken down into layers of insight, and these layers add tremendous depth to the piece. However, I occasionally felt that Arkenberg was being edgy for the sake of being edgy. The inclusion of “semen” in an otherwise innocuous list, for example, achieved nothing, and these shock-value moments shatter the glassy images that Arkenberg has spent paragraphs piecing together.

Nevertheless, “Final Exam” is an engaging read that surprises and entertains. The “extra credit” question is wonderfully sadistic; the answer paper given at the end provides an unexpected and rather exciting twist, and the thing writing it is absolutely ruthless. When it is finally revealed what happened to you and your husband, you’re left to wonder: who is writing the answers? Who is this terrible, all-seeing narrator? Filled with lines like “… the hideous satisfaction of the hard granite sound your hand made when it collided with his jaw”; this is a vivid, gripping story, and a particularly interesting take on the second person narrative that I very much enjoyed.

“The Flowering Ape” Alan DeNiro

At the Chartering School for Young Telepaths, gifted teenagers spend the days honing their powers, dodging the curfew avatars, and waiting to be chosen by a shepherd: one of the enigmatic aliens that allow humans to travel between the stars. When six young students come together at their local hangout, the Flowering Ape, the barriers of gender and status begin to break down under the bright lights and glass ceilings.

“The Flowering Ape” is an ambitious story about rape, control, and the tacit manoeuvres of social interaction. The protagonist, an intersexed telepath, is unflinchingly honest with us as he tries to win the affection of a boy named Kathy: “[…] why did I suddenly want him, the stooge? Was it his beard and blackened dress?” His stealthy progress as he gains the trust of the group is handled extremely well, and anybody who remembers their awkward teenage years will appreciate the subtle shifts in group hierarchy. DeNiro’s world is an interesting mix of postmodernism and “Beat culture” (like a new Kerouac SF), full of disaffected teens and fluid sexuality. Yet, while his protagonist is impressive, I think his story ultimately overreaches itself. Aside from a scene in which the characters all show each other their “parts” and swap clothes, the role of gender is never fully explored, and this was disappointing from a piece that makes such a show of its intersexed characters. I was left feeling like DeNiro had been building to a point (something about gender as a social construct) that in the end he never made. “The Flowering Ape” is entertaining in its way, mostly due to the narrator’s strength of character, but it is a challenging read with a sad conclusion.

“Free Range” by Bruce McAllister

In Orange County, California, it’s not often you see something genuinely supernatural. Not for want of looking, of course; from crystals to seances, Johanna’s tried it all. But when a creature from the night tears a gaping hole in her roof, Johanna knows she’s stumbled into something real, and something dangerous. The race is on to protect Johanna (and Mignon the cockapoo) from an unseen threat, and boyfriend Michael will do whatever it takes… even if it does involve an attic full of chickens.

“Free Range” is a cutesy, tongue-in-cheek tale about supernatural forces invading our lives. It opens with an eye-watering dialogue about “man poles” (with “man pole discussion” being McAllister’s polite, infuriating synonym for “sex”), then segues into the smitten ramblings of Micheal-the-boyfriend. In a nutshell, the Owls from Beyond the Fifth Star are stealing children and pets from our homes in the night. I had a great deal of trouble buying into McAllister’s mythology of owls that travel across the cosmos, and chickens that chant in concentric circles… but there’s an endearing absurdity to it. McAllister straddles a difficult line here between humour and ridiculousness, which is not helped by an unprompted, whiplash-inducing criticism of the Vietnam war. And yet, I came to quite like Johanna’s aloof galline saviours. There are only two possible reactions to this piece: love and hate, so be prepared, but I suspect that there is an audience out there for it.

“Missionaries” by Mercurio D. Riviera

“Take the leap, Cassie,” it says/thinks/sings.

Cassie and her fellow Saviours are crawling towards the abyss. It is the end of a pilgrimage, and the ritual requires endurance; their pain is exquisite as it burns inside their muscles. Pain is life, and the only fit offering to God. On a rogue, dead planet, the Saved One – an alien creature of dark energy – sits inside its pod of Bose-Einstein condensates, and watches them suffer.

“Missionaries” is the second of two standout pieces in this issue. Riviera takes a classic “science vs. religion” format and twists it, until the line between theology and physics is blurred beyond recognition. The story revolves around human attempts to communicate with the Saved One – a dark energy life form at the galactic centre, and the first of its species (the “Sagittarians”) to acknowledge humankind. It was Cassie’s ritual with the Saviours that finally engaged the creatures’ attention, and the scientists studying them hate this fact. The scientists’ disdain is combined deliciously with their begrudging concession that yes, it seems the alien is responding to your religious nonsense, and this creates an impressive tension between the two schools of thought.

Cassie herself is an excellent protagonist, whose story is told in flashbacks. The narrative jumps between past and present, which provides us with glimpses into Cassie’s life before the Saviours, and comes to represent her shattered perception of space and time. Her transition from atheism to devout worship is extremely compelling to read, and I enjoyed the use of narrative structure as a thematic tool. Riviera has found exactly the right balance here between entertainment and “cleverness,” so that his thoughts on the nature of the universe are just as engaging as Cassie’s tragic history.

I recommend this piece unreservedly. The science fiction contains enough genuine physics that Riviera’s world rings true, and the story leaves enough unanswered questions to keep us wanting more. Are the Saviours a cult? Was Cassie manipulated into believing? What happened to her at the abyss? Riviera proves once again that a piece doesn’t have to start with a bang for it to be instantly gripping, and as we’ve seen in some of his other works (e.g. Dear Anhabells), he is not afraid to enhance his storytelling by playing with its structure. This is an excellent piece of SF, and a thought-provoking read about mankind’s search for understanding.

“Possible Monsters” by Will McIntosh

A few hours ago, Cooper had been a ball player – a real baseball player, a pitcher for the Mudcats in Triple-A. But six years is a long time to go without getting noticed, and for Cooper, it was time to throw in the towel. At the end of a drunken car journey back to his parents’ place – his place now – Cooper is shocked to find the front half of the house smashed in, and something even stranger lodged inside.

“Possible monsters” is about the hell of missed opportunities. Thanks to an alien’s gift, Cooper is forced to watch what could, might, and should have happened to him if he’d only acted differently, when he begins to see alternate Coopers (the “possible monsters”) living out his alternate lives. The story opens with a bitterness that will be familiar to all of us who’ve had to give up and come home – that heady mix of self-loathing and disdain for the people around us. It’s not an easy emotion to convey; McIntosh’s craftsmanship here is impressive, and soon we’re presented with a convincing portrait of a man faced with the extraordinary, who tries to carry on with his mundane life. Unfortunately, when an alien encounter is overshadowed by banalities like an old girlfriend and a job at Moviemall, it leads to a rather boring story. There is an alien in your house: I don’t care about Moviemall. McIntosh has created precisely the feel he was going for, and deserves credit for sticking so ruthlessly to his characterisation: Cooper is a ridiculous, self-centred man, who comes within a hair’s breadth of “getting it” (of realising that you should take chances, and embrace the unknown), before swerving back into his own little world. Sadly, the result is a downright frustrating plot, and I wish McIntosh had been a little less stringent with it.

This is an average piece, improved somewhat by a few genuinely gut-wrenching twists (look out for the lottery syndicate), but it resolves itself too cleanly, too quietly, to achieve its potential. Worse, there is the faint smell of a moral lingering around McIntosh’s words, and it wrinkles my nose.

“Scout” by Bud Sparhawk

“My form might have been much reduced, to be sure, but nevertheless I retained my inherent humanity.”

It’s taken countless lives, and an almost desperate push by human military command, but Falcon and a few ships have made it into enemy territory. The Shardies have taken another colony, and wiped out every trace of human existence. If humans are to survive the coming bloodshed, they need to understand their aggressors, but all scans, all studies have failed. Now, Falcon will go straight to the enemy’s heart, and try to provide the first-hand intel that humanity desperately needs.

Bud Sparhawk’s piece has a shaky start at best. From firing the main character at a planet, inside a bomb casing, during an orbital bombardment, it stretches credulity to the breaking point. Throw in a few moments of clumsy action-movie drama (who doesn’t enjoy a quick explosion, and a protagonist getting hurled slo-mo through the air?), and you’ve got a real mountain to climb. Thankfully, Sparhawk seems to find his footing near the halfway point, and the better part of his creation is a harrowing, poignant tale of a soldier’s final moments in the service of mankind. There is something immediately difficult about Falcon. Even at the start, he seems devoid, as if his “inherent humanity” has been reduced somehow. As the horror of what happened to him is revealed, we grow progressively more attached to Falcon, until seeing him hurt further becomes almost unbearable. I even found myself getting caught up in his powerful anti-Shardie propaganda. The Shardies violate the essence of what it means to be human, and I felt rage towards them, towards these fictional aliens. That is testament to great storytelling.

There is a lot that I do not like about this piece – the Die Hard meets Demolition Man movie heroics, the stereotypical vision of a human society that has reconciled itself into a single whole during “the Enlightenment,” etc. But Sparhawk’s tale turns into something so haunting that all my complaints were eventually forgiven. Falcon suffers from a directionless rage: a desire for revenge for crimes he can’t remember, with only his own ruined body as evidence, and it is so easy to get swept up in it. “Scout” is the only piece in this issue with a moment of real, nail biting, edge of your seat tension, and it builds to a steadily more shocking conclusion as the full scope of events reveals itself. Don’t judge this piece by its opening paragraphs, read it for Falcon, and for the account of his suffering.

“The Widdershins Clock” by Kali Wallace

On even the most unremarkable of days, small events can combine to reveal glimpses of a story more intriguing than our own. Marta is folding her laundry when she discovers that her grandmother is missing. As she scours the town in search of grandmother Agnes, the invisible currents of time swirl about her, and deposit strange events at her feet. The hands of the Widdershins Clock are moving in erratic circles, and though time propels Marta onward, grandmother Agnes drifts further and further out of reach.

“The Widdershins Clock,” near plotless in itself, tells a story that hovers just out of our reach. On the surface, Wallace’s piece is about a woman looking for her grandmother, but it leaves you with the impression that something rather more interesting to do with causality and time is going on, all wound up in that mysterious clock and the arrangement of its gears. Yet, we are left uninformed, unsatisfied, and that becomes eminently frustrating. Marta quite clearly meets her older self at one point, for example, who has somehow travelled back through time, probably with the aid of the Widdershins Clock, but there is no confirmation of it. No explanation. Wallace uses mathematical concepts – Euclidean space, determinism and dynamic systems, etc. – to hint at the story she is actually telling, yet the piece never seems to “go” anywhere. Perhaps that is a comment on the cyclical nature of time… Despite occasionally poetic prose, I found little more than idle curiosity here, and unfortunately it seems that the title – the wonderfully named Widdershins Clock – is more fun to read than the piece.