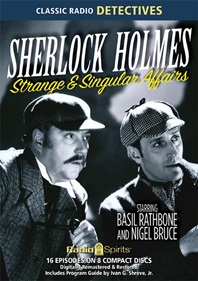

The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939-47) aired “Baconian Cipher” on May 27, 1946. This is the 21st since our first in 2013 and only the 3rd since 2022, so I thought another one was in order. During this incarnation of Sherlock Holmes on radio (the first coming in the early 1930s and the last running to 1959), Basil Rathbone (1892-1967) and Nigel Bruce (1895-1953) reprised their Universal studio film roles of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson for close to 220 episodes. Afraid of being typecast–-and following the cancellation of further Holmes films–-Rathbone wanted out of his radio role. Though the show’s sponsor at the time, Petri Wines, offered him a generous bump in compensation if he would continue, Rathbone declined. Following his final episode as Holmes at the end of May 1946 (which happens to be the one we present this week), the Holmes character was played by popular British actor Tom Conway (who was an excellent Holmes), with Bruce staying on until the series end in July of 1947. For several years (from September 1945–July 1947) scripts were written by the team of future F&SF co-founder Anthony Boucher, and Denis Green. Boucher, a diehard Holmes fan, would pen the outlines of scripts and Green would supply the details. They worked well together and the show flourished.

The New Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939-47) aired “Baconian Cipher” on May 27, 1946. This is the 21st since our first in 2013 and only the 3rd since 2022, so I thought another one was in order. During this incarnation of Sherlock Holmes on radio (the first coming in the early 1930s and the last running to 1959), Basil Rathbone (1892-1967) and Nigel Bruce (1895-1953) reprised their Universal studio film roles of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson for close to 220 episodes. Afraid of being typecast–-and following the cancellation of further Holmes films–-Rathbone wanted out of his radio role. Though the show’s sponsor at the time, Petri Wines, offered him a generous bump in compensation if he would continue, Rathbone declined. Following his final episode as Holmes at the end of May 1946 (which happens to be the one we present this week), the Holmes character was played by popular British actor Tom Conway (who was an excellent Holmes), with Bruce staying on until the series end in July of 1947. For several years (from September 1945–July 1947) scripts were written by the team of future F&SF co-founder Anthony Boucher, and Denis Green. Boucher, a diehard Holmes fan, would pen the outlines of scripts and Green would supply the details. They worked well together and the show flourished.

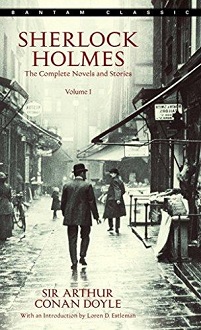

Since 130 years have passed since the first story of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson appeared in Beeton’s Christmas Annual magazine for December 1887 (A Study in Scarlet), much has been written, filmed, or dramatized of the most famous sleuth on the planet. In fact, the Wikipedia page devoted to Holmes, states that the Guinness Book of World Records’ lists the Holmes character as “the ‘most portrayed movie character in history’ with more than 70 actors playing the part in over 200 films.” And while hardly all inclusive, Wikipedia notes that those writing Holmes pastiches number the likes of Anthony Burgess, Neil Gaiman, Dorothy B. Hughes, Stephen King, Tanith Lee, A. A. Milne, and P. G. Wodehouse–to which I will add Manly Wade Wellman, Philip Jose Farmer, James Lovegrove, George Mann, Kim Newman, and Fred Saberhagen. It’s a sure bet there have been many others of genre interest over the years who have tried their hand at a Sherlock Holmes novel as well.

Since 130 years have passed since the first story of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson appeared in Beeton’s Christmas Annual magazine for December 1887 (A Study in Scarlet), much has been written, filmed, or dramatized of the most famous sleuth on the planet. In fact, the Wikipedia page devoted to Holmes, states that the Guinness Book of World Records’ lists the Holmes character as “the ‘most portrayed movie character in history’ with more than 70 actors playing the part in over 200 films.” And while hardly all inclusive, Wikipedia notes that those writing Holmes pastiches number the likes of Anthony Burgess, Neil Gaiman, Dorothy B. Hughes, Stephen King, Tanith Lee, A. A. Milne, and P. G. Wodehouse–to which I will add Manly Wade Wellman, Philip Jose Farmer, James Lovegrove, George Mann, Kim Newman, and Fred Saberhagen. It’s a sure bet there have been many others of genre interest over the years who have tried their hand at a Sherlock Holmes novel as well.

Sherlock Holmes first came to radio solely because of the tireless efforts of one remarkable woman. Edith Meiser (1898-1993) first brought Arthur Conan Doyle’s legendary sleuth to radio in 1930. She would write the scripts based on Holmes’s original adventures for the next 12 years (including this episode), sometimes branching out to pen tales in the Holmes tradition. Meiser was beloved of Sherlock Holmes fans and members of the Baker Street Irregulars (BSI), but until 1991 the BSI was a male-only organization. However, in part to rectify this situation she was welcomed into the Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes (ASH), originally an all-female Sherlock Holmes club, though it would later open its doors and become co-ed. The day every year that the BSI would hold its annual dinner, so too would the ASH, with Edith Meiser as its Guest of Honor. During the 1950s Meiser also wrote a daily Holmes comic strip, and was considered a great Broadway actress who also starred in films and early television, including appearances on I Love Lucy. One of the great unsung heroines of early radio (to the outside world at least), she died in 1993.

Sherlock Holmes first came to radio solely because of the tireless efforts of one remarkable woman. Edith Meiser (1898-1993) first brought Arthur Conan Doyle’s legendary sleuth to radio in 1930. She would write the scripts based on Holmes’s original adventures for the next 12 years (including this episode), sometimes branching out to pen tales in the Holmes tradition. Meiser was beloved of Sherlock Holmes fans and members of the Baker Street Irregulars (BSI), but until 1991 the BSI was a male-only organization. However, in part to rectify this situation she was welcomed into the Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes (ASH), originally an all-female Sherlock Holmes club, though it would later open its doors and become co-ed. The day every year that the BSI would hold its annual dinner, so too would the ASH, with Edith Meiser as its Guest of Honor. During the 1950s Meiser also wrote a daily Holmes comic strip, and was considered a great Broadway actress who also starred in films and early television, including appearances on I Love Lucy. One of the great unsung heroines of early radio (to the outside world at least), she died in 1993.

“Baconian Cipher,” as enigmatic as it might sound to the unenlightened, is actually a real thing as Sherlock Holmes reveals near the beginning of this quintessential Holmes episode.The tale begins with a French detective visiting Holmes in order to compare notes on the differences between English and French criminals, he believing that English criminals are rather dull, and to ask for Holmes’s help in the translations of Holmes’s monographs into French. In an attempt to prove that the English have their fair share of colorful criminals Holmes refers to a current newspaper, and a feature titled “The Agony Column.” It is a section where readers may write about almost anything, with the column’s readers entertained by some of the odd and outlandish accounts shared by their fellow readers. As Holmes, his visiting detective, and Watson scan that day’s column for interesting stories, they come upon one that baffles them at first. It stands out due to the fact that it has two fonts and type sizes instead of the one normally used by the paper’s typesetters, and the brief message is naught but a garble of letters. Remarking on the sloppiness of the message as not up to the professional standards of the paper, it is then Holmes who brings them up short with a reason for the message’s crude appearance. He spots that it is what is known as a cipher used by none other than Francis Bacon, who many theorize was the true author of Shakespeare’s plays. Bacon invented his code in 1605, and some have speculated that it was Bacon’s way to reveal that he was indeed the author of at least one of Shakespeare’s plays. True or not, leave it to Holmes to be the only one of the three to know of this bit of historical trivia. (For those interested, the Bacon Cipher is not invented for this radio drama but a real thing. To learn how the cipher works, I refer you to its own wikipedia page here.) This brief setup to the story scratches but the surface of what is to come. To discover the nature of the hidden message, who placed it for publication in “The Agony Column” and why, and how it leads to one of Holmes’s and Watson’s most unusual cases, you will have to listen to this finely crafted tale that begins innocently enough with the “Baconian Cipher.”

(The CD linked above contains this episode and 15 others.)

Play Time: 29:56

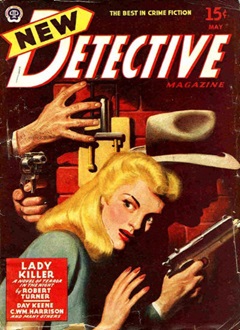

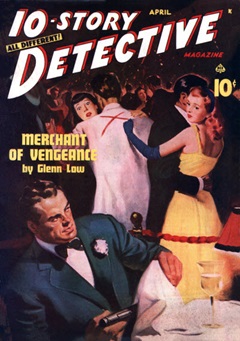

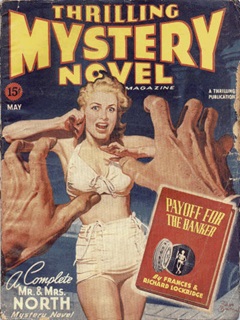

{This episode aired on a Monday evening in late May of 1946. The next afternoon after school found the neighborhood gang at the nearby newsstand, eagerly searching for mystery and detective pulps they hoped would provide the kind of excitement they felt while listening to the Sherlock Holmes drama the night before. They were in luck and brought home the titles shown below. New Detective (1941-55) promoted the magazine as featuring the best in new crime fiction, with much of its fare focusing on police detectives by some of the field’s most popular authors. From 1942-55 it held to a regular bi-monthly schedule except for 1946 when for some reason it shoehorned in a 7th issue in February. 10-Story Detective (1938-49), like New Detective, featured stories centering on police and detective action stories. While it managed a bi-monthly schedule for virtually its entire run, it produced only 5 issues in 1946. Thrilling Mystery Novel (1935-51) began as a weird menace pulp but after a few years began its shift to more conventional mysteries. This proved a wise decision as it ran for a respectable total of 88 issues. It was a bi-monthly until the war took its toll with it and other pulps with the paper shortage. From 1943 forward it couldn’t quite manage a full 6 issues a year but did manage 5 in 1946.}

[Left: New Detective, 5/46 – Center: 10-Story Detective, 4/46 – Right: Thrilling Mystery Novel, 5/46]

To view the entire list of weekly Old Time Radio episodes at Tangent Online, click here.