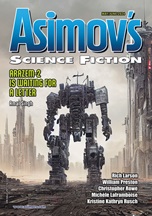

Asimov’s, May/June 2024

Asimov’s, May/June 2024

“Barbarians” by Rich Larson

“Last Thursday” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

“Arazem-2 is Waiting for a Letter” by Amal Singh

“The Rattler” by Leonid Kaganov

“The Shadow Box” by M. Bennardo

“To Make an End” by William Preston

“Renting to Killers” by Elena Pavlova

“In the Palace of Science” by Chris Campbell

“Cynthia in the Subflooring” by Christopher Rowe

“Maragi’s Secret” by Michèle Laframboise

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

This issue is unusual for a couple of reasons. It offers three full novellas, instead of the usual one or two, as well as two newly translated stories from Eastern Europe.

The novella “Barbarians” by Rich Larson features a pair of starship operators who have been involved in questionable activities in the past. One of them is only a disembodied head kept alive in a special solution, the result of his imprisonment for smuggling. The other is his partner, best friend, and narrator.

The pair are hired by twin brothers to take them on a tour of a dead planet-sized organism orbiting a star. The creature is so huge that it has its own ecosystem, including deadly plants and animals. Besides the inherent danger of the environment, the hidden motive of the twins leads to a much more hazardous situation.

The exotic setting is richly imagined and creates a true sense of wonder. The plot moves quickly, with a great deal of suspense. In addition to being a compelling science fiction adventure, the story also raises serious issues of guilt, greed, and loyalty.

In “Last Thursday” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch, a time traveler from the future arrives in Las Vegas during the COVID-19 pandemic. He finds the time and place dreary. In response to a sign posted outside a bar, he makes several illicit trips back further, one week at a time. Eventually he faces the question of whether the past should be, or even can be, changed.

The premise of altering the past is a familiar one. More effective is the story’s account of a tragic event the time traveler witnesses and tries to prevent.

The title character in “Arazem-2 is Waiting for a Letter” by Amal Singh is a robot, formally a war machine and now performing various mundane tasks on the demand of clients he cannot refuse. (Male pronouns are used throughout the story.) Like others of his kind, he hopes to win his freedom via a slow bureaucratic process. Meanwhile, mobs of protesters attack the robots.

The author manages to make the protagonist and other robots into characters with which one can empathize. The fact that the main character was a combat device is vital to the plot, but one has to wonder why his armaments were not deactivated before he became a civilian worker. Part of the resentment of some people against the robots is their belief that the machines took away the honor of battle from humans. I found it hard to believe that very many soldiers would rather face death in war rather than let robots do the dirty work.

“The Rattler” by Leonid Kaganov is translated from Russian by Alex Shvartsman. A strange thing, possibly living or possibly a machine, appears on Earth. About once a second, it uses a mysterious power to randomly kill a person, who might be anywhere on the planet. Anybody who attempts to attack it is immediately killed as well. A team of television newscasters interview a professor who suggests a possible way to defeat the thing, even though just talking about it causes him to be killed also.

Partly a puzzle story, with discussion of game theory, this grim tale can also be seen as an allegory for ways in which people might deal with powerful oppressors. (An afterword from the translator makes it clear that the text includes a hidden message of support for Ukraine during its struggle to fight against Russia’s invasion. This is a remarkably brave action for a Russian author to take while living under a regime that brutally represses dissent.) The situation, as intriguing as it is, is highly artificial, lessening its intended impact.

In “The Shadow Box” by M. Bennardo, a couple living on wilderness land discover a tall pole holding a large box. Their young son finds a website claiming that such a thing, built in a very specific way, is meant to attract shadow birds, which are impossible to see or photograph. Going along with what they think is a hoax, the parents learn an important lesson about the boy’s passionate desire to prove the birds exist.

It is possible to interpret this story as either fantasy or mainstream fiction, as the shadow birds, by definition, cannot be witnessed directly, and the only hints that they might be real could easily be explained in more mundane ways. Be that as it may, this gentle tale makes for pleasant reading, although the lack of a definite answer to the existence of the shadow birds may frustrate some readers.

In the novella “To Make an End” by William Preston, brother and sister discover a fabled hero in suspended animation within a hidden underground chamber. Using clues from times in the past when he appeared, they manage to track him down so he can deal with serious problems facing Earth. In particular, people disappear without explanation, including their parents. When he awakes, the hero discovers that his exploits have not only inspired many novels, but a cult as well. An apocalyptic event leads to an encounter with an old adversary.

This synopsis may not be fully accurate, as the current story is the latest in a series that began in 2010, the previous entry appearing ten years ago. Familiarity with previous stories is probably necessary to fully appreciate this final tale.

There are hints that the hero is based on the pulp magazine character Doc Savage. The author’s attempt to make such a figure more human, and to tell a more sophisticated story about him, is admirable. The extraordinary abilities of the adversary are much less realistic.

“Renting to Killers” by Elena Pavlova is translated from Bulgarian by the author and Kalin M. Nenov. Two thugs with body enhancements rob and assault a couple who run a boarding house. One of their guests, who seems to be completely harmless, sets out after them

To say anything else about the plot would give away too much, although certain outcomes are predictable. Suffice to say that it has something to do with the relationship between reality and fiction. The setting is subtly strange, although it’s impossible to tell if the story takes place in the future or another world. Sensitive readers should be aware that the text includes explicit violence.

“In the Palace of Science” by Chris Campbell is set in the early 20th century. It takes the form of phonograph recordings from the narrator. He explains how he came to work with a reclusive genius in his extraordinary home full of highly advanced scientific equipment. Together they reactivated an ancient robot that went on a rampage. When the machine returned, they faced an even greater challenge.

I can both praise and damn this story by saying that, if it had appeared in Amazing Stories in the late 1920s or early 1930s, it would be considered a classic of early science fiction. The author’s style is much more sophisticated than most SF writers of that time, but the plot is similar to something that might have appeared in the yellowing pages of Hugo Gernsback’s magazine. I might also quibble about the unsolved mystery that occurs at the end of the story.

“Cynthia in the Subflooring” by Christopher Rowe is a brief tale in which the title character falls through the floor of her aunt’s house, winding up trapped in the space beneath with a bizarre being. After some conversation with the creature, she continues her weird journey.

This is a strange, quirky little story, something like Alice in Wonderland mixed with a peculiar version of the afterlife. It may be a telling point that I found a long paragraph describing in great detail what goes into the building of a floor the most interesting part.

The novella “Maragi’s Secret” by Michèle Laframboise concludes the issue. It takes place many centuries after the surface of the Earth became unlivable, so people dwell in floating cities and travel in airships. (Despite the futuristic setting, the story feels more like steampunk set in Victorian times.) A young woman accompanies her father aboard his airship. Among the many challenges she faces are the inherent dangers of working on the outside of the vessel; the need to disguise her sex in a culture where a female working on an airship is unacceptable; the unwelcome attentions of a young man who knows her true identity; the presence of the extremely valuable egg of an albatross, located in a nest on the surface of the airship; the theft of her father’s gold compass; and a collision with another vessel.

Obviously, there’s plenty of plot; too much, perhaps. I found myself wondering if I was supposed to be primarily concerned about the egg, the accident, or the compass. The most dramatic scene takes place long before the end, so the rest of the story is anticlimactic. The author supplies more realistic details about the operation of an airship than in most stories dealing with such vessels, but their presence is likely to be overly familiar to readers of steampunk.

Victoria Silverwolf is currently reading Adventures in Time and Space, a pioneering science fiction anthology first published in 1946.