Sci Phi Journal, Spring 2024/1

Sci Phi Journal, Spring 2024/1

“To Catch The Light Off Other Stars” by A. J. Rocca

“Untitled” by Jeff Currier

“The Map And The Territory” by Isa Robertson

“Charlie v. Inman” by Mary G. Thompson

“Stereopolis” by Gheorghe Săsărman

“The Problem Child” by Richard Lau

“The Cleft” by Javier Fernández

“Don’t Eat The Garum!” by Matias Travieso-Diaz

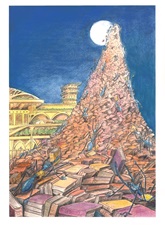

“The Mound” by Nicolas Badot

“Between Scylla And Charybdis” by Dexter McLeod

“In Astrorum Mari” by Edmund Nasralla

“The Taming Of The Slush” by Michèle Laframboise

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

A dozen new works blending speculative fiction with philosophy appear in this issue.

In “To Catch The Light Off Other Stars” by A. J. Rocca, Lucifer travels throughout the universe, aided by another rebel angel, in order to bring sin to all the lifeforms he can find. Pausing in his endless quest to corrupt all sentient beings, he discovers the true identity of his assistant, and learns about the hidden reason behind his odyssey.

This is a theological fantasy likely to appeal to readers of science fiction as well. Much of the text deals with the various organisms tempted by Lucifer, and these are quite imaginative. The story’s conclusion offers much food for thought.

In “Untitled” by Jeff Currier, Charles Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, somehow winds up in a pub where multiple paradoxes occur. Some will be familiar to most readers, such as the time traveler who kills an ancestor. Others require familiarity with logic and mathematics.

Essentially a catalog of paradoxes (including the title of the story itself), this lighthearted jape will amuse readers who take pleasure in such things. Others may find it self-indulgent and lacking a real plot.

In “The Map And The Territory” by Isa Robertson, a man makes a very detailed map of an unexplored area. Forced to remain in one place after an injury, he discovers that his map is far from ordinary.

I am deliberately being vague about the story’s speculative content, as this is not revealed until midway through the text. The idea is not completely original, but the way it is used in the climax is provocative.

“Charlie v. Inman” by Mary G. Thompson takes the form of a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States. The case involves an alien discovered by a human couple on Earth, and whether they can legally consider it their property.

The story may be intended as satire, possibly directed at the legal notion of original intent. Be that as it may, this brief tale offers little more than its basic premise.

“Stereopolis” by Gheorghe Săsărma, translated from Romanian by Monica Cure, is one of a series of tales about imaginary cities. (Many others, translated by Ursula K. LeGuin, can be found in the collection Squaring the Circle.) The title refers to a “fully dimensional” city. The inhabitants must have “spatial orientation” to dwell there without ill effects. Unfortunately, this ability is not passed down by genetics, so those who possess it face the possibility of their children being unable to live in the city.

My use of parentheses indicates that I am not at all clear as to what the author means by these terms. Are these two-dimensional beings living in a three-dimensional city, with a nod to Edwin A. Abbott’s 1884 mathematical fantasy Flatland? Are higher dimensions involved? I simply do not know. More perceptive readers may be able to enjoy this enigmatic work as an intellectual exercise.

“The Problem Child” by Richard Lau consists of two letters from a friend of Albert Einstein’s father. They come from different universes, offering opposite versions of what became of Einstein.

The story opens with a quote from Einstein himself that makes the story’s theme crystal clear. There are no surprises in the plot, and this is a very simple example of alternate history.

“The Cleft” by Javier Fernández, translated from Spanish by Álvaro Piñero González, is an example of fiction set in prehistoric times, often considered a branch of speculative fiction. While hunting, a man is badly injured and falls into a deep crevice, unable to escape. Another man passes by and reacts to the screams of desperation he hears in a way that suggests the origin of a certain aspect of human culture.

Without giving too much away, it can be said that the story offers an ironic look at something that many people consider to be of great importance. (A brief introduction by Mariano Martín Rodríguez reveals this aspect of the work, and can be thought of as a spoiler.) The author’s portrait of early human psychology is interesting, but one may question the plausibility of the premise.

“Don’t Eat The Garum!” by Matias Travieso-Diaz is set in the Roman Empire at the time of the emperor Tiberius. The military leader Germanicus has a dream in which his dead father gives him the warning found in the title. Heeding this, he manages to escape being poisoned and goes on to become Emperor himself.

The beginning and end read like a dry account from a history book. The middle is more of a real story, and is far livelier. I had to do some research to realize that this is a work of alternate history, as the real Germanicus died before he could become Emperor. Those well versed in history are likely to realize this more quickly than I did.

As a minor quibble, the author apparently shares the common belief that a vomitorium was a place where the ancient Romans went to vomit. In fact, the term refers to a passageway where crowds could quickly exit a stadium. I am too ignorant about Roman history to know whether the rest of the story is accurate or not.

The title of “The Mound” by Nicolas Badot refers to a hemisphere, said to contain all knowledge, that is always on the horizon no matter how long one approaches it. The narrator is one of those selected to make a mental journey to the mound, from which no one has ever returned.

I have badly explained the plot of this surreal tale, as it is very difficult to follow. The author creates an effective mood of strangeness, even if the concepts are vague.

The narrator of “Between Scylla And Charybdis” by Dexter McLeod is an inmate in a prison that orbits around and between a pair of black holes. The implication is that the prisoners, outside normal time, will be trapped there until the two black holes disintegrate after a vast period of time.

There is little to this tale other than its premise. The author powerfully conveys the narrator’s plight, but the situation is inherently static, without possible resolution.

“In Astrorum Mari” by Edmund Nasralla is set in the year 4357. It takes the form of a letter from the Pope to bishops on a distant planet. Not long before the story begins, one of the Catholic Church’s starships discovered humans on the planet, who apparently arrived there by miraculous means in Old Testament times. They quickly accepted the teachings of the Church, but now the Pope warns of possible theological disputes.

Much of the text consists of exposition, as the Pope describes the situation to people who should already be aware of it. The point may be that all religions are prone to schism. Otherwise, there seems to be little to the story, as with some other works in the magazine, beyond its basic idea. I must admit that the author convincingly conveys a Papal style. (By the way, the title can be translated from Latin as “In The Sea Of Stars.”)

“The Taming Of The Slush” by Michèle Laframboise ends the issue on a light note. In the future, automated writing programs allow a single so-called author to send tens of thousands of manuscripts to an editor at once. The reverse side of the coin is that editors have programs that can reject them as quickly.

Apparently intended as a satire on the way publications are now flooded with worthless manuscripts produced by artificial intelligence, this droll tale is likely to amuse writers and editors. Those outside these professions are likely to appreciate it as well, if not to the same degree.

Victoria Silverwolf would like to point out that this issue also contains an essay by fellow Tangent Online reviewer Mina, the text of which quotes extensively from the Noble Editor.