Tangent Online Presents:

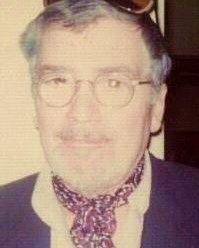

An Interview with Alfred Bester

(1913-1987)

Interviewer:

Dave Truesdale

Location:

MidAmeriCon, 34th World Science Fiction Convention

Kansas City, MO, September 2-6, 1976

Muehlebach Hotel

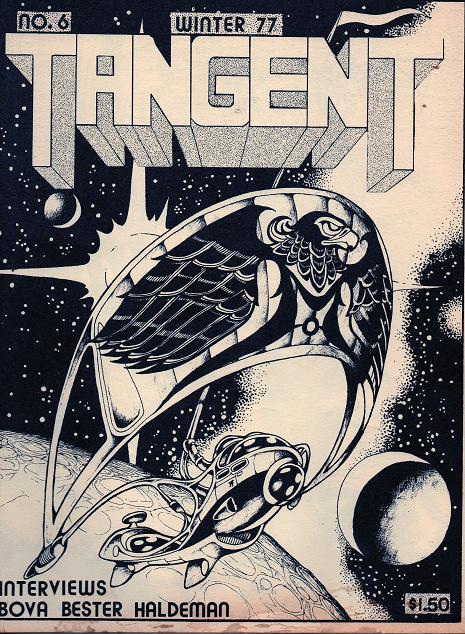

Interview originally appeared in Tangent #6, Winter 1977, and is reprinted here for the first time.

(Front cover art by Robert Fuller — Rear cover art by Barry Kent MacKay)

Introduction

This was my first worldcon, and I think only my fourth convention. I was a month shy of my 26th birthday. I had driven home from Oshkosh, Wisconsin to Kansas City to stay with my folks during the convention. The convention was almost over and I and a few friends were resting in the lobby of the Muehlebach hotel when I caught the eye of Alfred Bester. Alfred Bester! I nod and we say hello. The next thing I remember I had asked for an interview to which he readily agreed. I was shocked. I was going to interview Alfred Bester? We soon found ourselves in one of the hotel bars at a corner booth, my friends and I looking outward and Alfie, pulling up a chair from a nearby table, with his back to the room. For two hours we sat and talked, drinking pitcher after pitcher of beer (and a few other adult beverages, courtesy of Alfie). Transcribing the tape was difficult. Alfie talked a mile a minute, emphasizing this word or that phrase, and I wanted to try and capture the excitement and passion he brought to our talk. Even after all these many years I still feel the excitement of my 25 year-old self as I sat there with Alfred Bester for almost half an afternoon, drinking, and getting this interview. It was a wonderful experience.

Alfred Bester’s accomplishments are too many to list with any attempt at specificity (he would write for radio, comic books, and television, as well as travel to many parts of the world for Holiday magazine), so here are some of the highlights:

The Demolished Man (1953) won the first science fiction achievement award for Best Novel. (Two years later at the worldcon the award was officially chirstened the Hugo, so Alfred Bester is credited as winning the first-ever Hugo for Best Novel.)

1956 saw The Stars My Destination published. It is acknowledged as one of science fiction’s enduring classics.

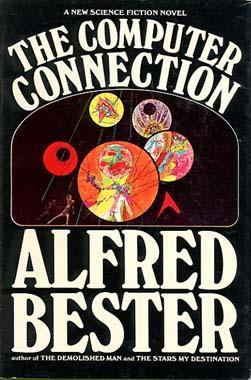

The Computer Connection was serialized first in the November 1974 through January 1975 issues of Analog as The Indian Giver. It was nominated for both the Hugo and Nebula awards.

He was highly regarded as a brilliant short story writer, many of his stories also considered classics. Though there have been several collections of these stories over the years, probably the best of the lot is Virtual Unrealities (1997).

Alfred Bester was named a Science Fiction Writers of America Grand Master in 1987 (only the 9th), as he lay dying. He would pass away before the honor was officially awarded, but as Grand Master’s are given only to living writers, he nevertheless met this eligibility requirement.

For those who have not had the pleasure of reading Alfred Bester, his work is essential to an overall understanding of modern science fiction (primarily the earlier pair of novels noted above and virtually all of his short fiction from the mid-40s throughout the 1950s).

No sooner had we sat down and ordered drinks than Alfie began talking. It took me several minutes to dig out the tape recorder and set things up. The interview begins in the middle of Alfie speaking to a question about his (then) newest book, The Computer Connection.

ALFRED BESTER: (On the character Rajah in The Computer Connection) My editor friend said to me, Alf, you’re not going to believe how this man behaves. This guy is a God; he is a God. And this next took place in a resort north of Monte Carlo back in the 40s: Now, as a God he knows no rules, he knows nothing; he is indifferent to civilized behavior. I have been with him when this rajah was walking with his entourage through a lobby, and he had stopped an unzipped himself and peed into a potted plant. And I said, “Oh, Harry, that’s not true.” And he said, “I’ve seen it. I’ve seen him again in a gambling casino walking to the roulette table to blow ten gillion dollars–and suddenly he is overtaken and he squatted down and shat on the floor in public–and the attendants rush up to him with toilet paper or silk scarves or something and wipe him.” That’s the guy I used for the Rajah in The Computer Connection.

ALFRED BESTER: (On the character Rajah in The Computer Connection) My editor friend said to me, Alf, you’re not going to believe how this man behaves. This guy is a God; he is a God. And this next took place in a resort north of Monte Carlo back in the 40s: Now, as a God he knows no rules, he knows nothing; he is indifferent to civilized behavior. I have been with him when this rajah was walking with his entourage through a lobby, and he had stopped an unzipped himself and peed into a potted plant. And I said, “Oh, Harry, that’s not true.” And he said, “I’ve seen it. I’ve seen him again in a gambling casino walking to the roulette table to blow ten gillion dollars–and suddenly he is overtaken and he squatted down and shat on the floor in public–and the attendants rush up to him with toilet paper or silk scarves or something and wipe him.” That’s the guy I used for the Rajah in The Computer Connection.

TANGENT: I was amazed at the mish-mash of weird characters you were able to assemble, and make fairly plausible, in The Computer Connection. All in one setting.

BESTER: (Chuckling) I was amazed, too.

TANGENT: In The Demolished Man you used the best elements of the detective genre and the science fiction genre and combined them, but what struck me was the ESPer party, the way you laid that out on the page. Was that new for back then?

BESTER: I don’t know if it’s true, but to the best of my knowledge I was the first person to do that. I didn’t borrow from the mainstream or anywhere else. I knew exactly what I was doing with that. Now, I have a party, an ESPer party, and I melded all these characters I needed to develop the plot, to move it along–and you know damn well that when you write, a scene is no damn good, it’s not valid unless it moves the action. Everything must move forward; you must at every point move forward. You’ve got to move that story; man, get that story off its ass and keep it going! And too many writers, I’m afraid, fall in love with a scene that is not moving anything, and they keep it anyway. And I think it’s a mistake to do that.

However, this was coming up and I said, okay, we’ll run a party scene here, there are some characters I want to introduce at this point; I’ve got to establish them because I want to use them in the future, but c’mon man, this is a mindreading party, this is an ESPer party! What the hell would an ESPer party be like? How can I make it different? I sweated this one out David, I really did.

I can’t think of all the original alternatives that I had in mind and discarded, but I went over and over them for days. In fact, it took me an entire day, from about six in the morning to about five in the afternoon when it hit me, “Oh, Jesus shit Mariah, I’ve got it!” And I grabbed a great big legal-size pad of yellow paper–no lines–and I just began to block the lines. As I was doing this, suddenly I thought party game, game, game, make it a GAME! And then I went on to what kind of a game would espers play? But also, what kind of a game could be visual with the typography? So then I had to slave a little more and work and I made little pictures of houses and things like that in order to fuse the two mediums. So, that’s how it came about. Nobody said much about it. I wish they had, it would have made it easier. That one I did from scratch.

TANGENT: I couldn’t make up my mind where my sympathies lay–with the hunter, Lincoln Powell, or the hunted, Ben Reich. You kept switching them on me.

BESTER: (Laughing) Yep! Thank you for spotting that. Well, look, I’ll tell you; very often I write out of irritation of clichés. And by that time I was so fuckin’ goddamned sick and tired of the good guy/bad guy cliché, in the first place. In the second place, I was rooting for the bad guy. I am always with the anti-hero; I’ve always, all my life, been an anti-hero man. So I of course concentrated on Ben Reich. But my big problem was, David, I had a lot of trouble with the hero, Lincoln Powell. When I was writing I had to keep going back and say to myself, C’mon Alf, you’re letting him down, he is not sympathetic enough, he is not balancing. Reich gave me no trouble at all, because in him I reflected all of the son-of-a-bitch in me. So I was very sympathetic toward him; I felt for him.

BESTER: (Laughing) Yep! Thank you for spotting that. Well, look, I’ll tell you; very often I write out of irritation of clichés. And by that time I was so fuckin’ goddamned sick and tired of the good guy/bad guy cliché, in the first place. In the second place, I was rooting for the bad guy. I am always with the anti-hero; I’ve always, all my life, been an anti-hero man. So I of course concentrated on Ben Reich. But my big problem was, David, I had a lot of trouble with the hero, Lincoln Powell. When I was writing I had to keep going back and say to myself, C’mon Alf, you’re letting him down, he is not sympathetic enough, he is not balancing. Reich gave me no trouble at all, because in him I reflected all of the son-of-a-bitch in me. So I was very sympathetic toward him; I felt for him.

But I really hate heroes, so I had to slave over Powell. It was murder, really.

You know, Robert [Heinlein] said to me once–we were talking shop, writing techniques and stuff like that–and Robert said I’ll tell you what I do, Al. What I do is get a bunch of characters together and I get them into difficulties, and by the time I can hear them talk they’ve solved their difficulties and I’m finished.

I was absolutely flabbergasted! I can’t even start a story until I can hear my characters talking. I’ve got to know who they are, what they are…I’ve got to identify with them completely.

TANGENT: Does the story have a tendency to take over, then?

BESTER: When I got about two-thirds of the way through The Computer Connection I knew where I was going and I felt secure enough…and the notes for it, you know, bales of notes cluttering up everything, and I figured I didn’t need them any more so I bundled them all up. But I came across the final outline! The results of two months of planning. And I reread the final outline which ran about 14 or 18 double-spaced pages, and it was a splendid outline, it was a hell of a story…but (laughing) it had nothing to do with the book.

The book had taken over. I looked at the outline and smiled and thought, Well, should I just save it for laughs? Aw, fuck it, and I burned it, too!

These stories very often take over and sometimes I kick like a steer. In The Computer Connection again, the 13 year-old little doll, Fee-5, began to take over, and I gave her a lecture: “Look, doll, you’ve got to mind your own business. I cannot permit you to take over.” She was taking over that story, getting stronger and stronger, and I told her to mind her own business, to behave herself, and she wouldn’t, she wouldn’t, she wouldn’t. So finally I sat down–and it took me a week–and I said to myself okay, you’ve got to kill her off…but her death must move the story. It took me a few days to figure out how to make her death move the story, and it took a couple more days to get the courage to write it–less than half a page–but it took me agonizing hours to bring myself to do it–and I’m not exaggerating, this is the truth–after I killed her off I went into shock and couldn’t write for a week, but it was the end of the chapter. But I couldn’t go near the book, I didn’t want any part of it. You know, I got a little moist around the eyes, drank a little too much, went to the local saloon with some bucks and sat around and drank up a storm with everybody. “Ha, ha, ha!” Cheerful, cheerful, you know….

I was really deeply depressed, deeply involved with her.

Months after the fact when Ben Bova read the book, Ben, I discovered, was as shocked and depressed as I was. He said to me, “Alfie, did you have to?” And I said, “Yes, I had to. You know that, Ben.” And we were discussing rewrites, changes, and so forth, and Ben said to me, “Please, please, please, for my sake and for the reader’s sake, please give her a chance of coming back.” So I did it for Ben.

I loved that kid, that little son-of-a-bitch (chuckling).

TANGENT: Other parts or scenes of the book seemed so mad, surrealistic, when viewed with a fish-eye, in perspective. Elephants crashing through floors and living in basements; again that mixed-up bag of weirdos for characters…

BESTER: (Laughing) I’m demented, you know that. I had a lot of fun writing those scenes; sometimes you can have a lot of fun when you write–not as often as you’d like, though. And then you have to be very careful with yourself and say, “Hey, hey, hey, hey, hey! You’re having too much fun, watch yourself now, man.” And that’s when you start editing. Because you know, every writer, good writer, is half writer, half editor. We are editing ourselves constantly. It’s a vertical sport, not horizontal. That editor in you is looking left at the writer and saying “C’mon, mind your manners, man.”

(At this point a fan stops by the table and asks for an autograph. We all drink some more…and lose our place.)

TANGENT: Do you mind if I get frank?

BESTER: Me? You ask me a question like that? What’s the matter with you?

TANGENT: Do you think you had too many madcap characters in The Computer Connection, and too many things going on all at once, for you to bring them together effectively? It seemed too thin in parts.

BESTER: Turn off your set while I think….

TANGENT: (Click)

BESTER: Yes, that’s half of the answer. The true answer is this: I have a terrible, terrible weakness as a writer. I have a complete lack of confidence in the spine of the story, of the essential story-line. And as a result of this lack of confidence I try to cover it. I fake by covering it with glitter, with bangles, with sequins.

A nice young lady said to me once that this is what you do, Alfie: you design a classic evening gown, but then you’re unsure of yourself so you cover it with spangles. And that’s what I did with The Computer Connection, that’s what I do with all of them. People say to me, “You put so many different ideas into your stories that you’ve got enough for four novels in any short story.” It is true. It is true because–for reasons I don’t understand–apparently, I am up to my ass in ideas. Ideas are nothing for me. I’ve got big notebooks crammed with ideas that I’ve never been able to use. But this is not the point of my accusation against myself. My accusation is, a lack of faith and confidence in the basic story-line. After all these years I still try to cover it up, and it’s like the hand is quicker than the eye. What I’m virtually doing is saying oh, look at this, get a little fact from that, oh, here’s a fine new character–and all of this so you’re not looking at the central story-line. I’m trying to keep you away from it.

TANGENT: You write like you think, then? So fast?

BESTER: Right, right!

TANGENT: Have you ever been able to tone yourself down?

BESTER: Naw, I’ve tried again and again. It’s out of the question.

BESTER: Naw, I’ve tried again and again. It’s out of the question.

You know, in the early days of the magazines when I was writing an occasional story for Thrilling Wonder, the editor took me in hand and laid it out for me. He said, “Al, you are writing in a straight line that goes up 90 degrees from the bottom to the top. You can’t do that, you’ve got to write saw tooth. You give’em a peak then a rest, a peak then a rest, and so on.” He went on to say that I demand too much of the reader. And I do try, I sincerely try to give them a rest period, but my idea of a rest period is apparently somebody else’s idea of high action, so what can I do? I don’t want to write an average script. I want to knock your block off every time. And in case you get up then I want to knock you down again so you can’t get up. I want to knock you dead.

TANGENT: What do you think of writers writing up or down to the readers, that whole question?

BESTER: Oh, boy. This is a very sore point with me. I have fought with networks, with producers, with directors, with editors–I have fought the world over. Now, I talk as a professional editor. I hate editors; they are always putting the reader down. And they say to me, over and over again that I expect too much of the viewer, of the reader, and I keep saying to them that a ten year-old child is brighter than they are.

Now, I treat everybody as an equal. I figure everybody is as goddamned smart as I am, and probably a helluva lot smarter–even if they’re nine years old–and I am writing for them.

Now, if you say I expect them to come up to my level… I hate to think of it in terms of “coming up.” I expect to meet them on a mutual level and I will not lower my level for some dumb, stupid, cockamamie editor, or director, or producer, who says, “Hey, Alf, they’re never going to understand that.” I say, “Yes, they’ll understand it! Of course they will. Give’em a chance for Chrissake.”

That is one of the reasons I’ve knocked off writing television, because they want me to lay it in their laps, make it easy for them.

TANGENT: How can one expect to raise the “level” of the mass market audience in TV? It’ll probably take thirty years!

BESTER: You can do it overnight for Christ Jesus sake. Look what happened with Upstairs, Downstairs. It’s a sensation in New York and that’s been five years now. The people loved it.

TANGENT: If the people get the type of government they deserve, then they’ll also probably get the type of television, books, etc., they deserve. But if the mass medias are always cramming certain things down everyone’s throats then they don’t even have a chance to know what they might want. How would you reconcile this?

BESTER: It’s very easy…I’m anti-democratic. I’m an elitist. I do not believe that all men are created equal in terms of talent, ability, and intelligence. They are all created with the right to equal opportunity, to equal rights, but there must be limits. I want to go back to levels of society. One does find one’s own level, and that’s perfectly true.

In one of Shaw’s earliest plays he makes the point. All of us, each of us invariably find our own level. We cannot remain in a level which is artificial for us. Either we move up or we move down or we stay where we are, but we find our own level.

I do not believe–I’m an elitist I say–that there should be only one level of entertainment. This is why I so strongly support N.E.T. The other networks are in business to make money, and we all know the level of people they cater to. Good luck to them, that’s fine. We know the kind of artists who are doing that work, and they’re doing it for a fast buck. Again, good for them; I have nothing against them. But some of the actors–Shirley Booth for instance, the greatest actor in the American theatre–was dirt poor until she finally got that cockamamie television series Hazel. And that lousy, rotten, stinkin’ show has made her secure for the rest of her life.

(Here there is a pause while more booze is ordered and delivered.)

BESTER: (Just chatting off the top of his head.) My only problem if I ever would go to the Playboy mansion would be keeping a straight face–like my one session with Campbell. Oh, my God!

TANGENT: Would you tell us about that?

BESTER: Well, what happened was–this is my second collection called Star Light, Star Bright. I wrote a story called “Oddy and Id” and back then I was deeply into using psychiatry in my stories–Freud and Jung–as motivations for characters, and stuff like that. And this story had a Freudian background. I mailed it to Campbell and about two weeks later he called and said he liked the story, wanted to buy it, but would I make some changes in it. Would I also come out to Astounding, which was located somewhere out in the boondocks of New Jersey. I was delighted, never having met the man before. I idolized Campbell. I had this tremendous mental picture of him. But I said that sure I’d come. So I hopped on the train and went wherever the hell and gone out there in New Jersey, and I come to this building which was this really sleazy looking printing plant. So I go up to the offices of Astounding Science Fiction, right? Well, John’s office was about the size of this little alcove right here, and there was enough room for Campbell’s desk and chair, and a chair for one visitor, and that’s all the room there was.

BESTER: Well, what happened was–this is my second collection called Star Light, Star Bright. I wrote a story called “Oddy and Id” and back then I was deeply into using psychiatry in my stories–Freud and Jung–as motivations for characters, and stuff like that. And this story had a Freudian background. I mailed it to Campbell and about two weeks later he called and said he liked the story, wanted to buy it, but would I make some changes in it. Would I also come out to Astounding, which was located somewhere out in the boondocks of New Jersey. I was delighted, never having met the man before. I idolized Campbell. I had this tremendous mental picture of him. But I said that sure I’d come. So I hopped on the train and went wherever the hell and gone out there in New Jersey, and I come to this building which was this really sleazy looking printing plant. So I go up to the offices of Astounding Science Fiction, right? Well, John’s office was about the size of this little alcove right here, and there was enough room for Campbell’s desk and chair, and a chair for one visitor, and that’s all the room there was.

And I came in and shook hands with him, and I’m fairly big but he was enormous; he towered over me. He was about the size of a defensive tackle. Anyway, we sit down (and I’ve got a great sense of humor, and that’s why I could never get along with him). I had the same trouble with Arthur Clarke. I said something once about never being able to get along with Arthur Clarke because he didn’t have a sense of humor. And Arthur wrote me this bitter, wounding letter, and the gist of it said, “I have so got a sense of humor.” But he had included clippings from his reviews that he said proved he had a sense of humor.

Anyway, Campbell said to me out of the clear blue sky, “Of course you don’t know it, you have no way of knowing it yet, but psychiatry–psychiatry as we know it–is dead.”

And I said, “Oh, Mr. Campbell, surely you’re joking.”

And he said, “Psychiatry as we know it is finished.”

And I said, “If you mean the various Freudian schools and the quarreling that’s going on between them…”

He looked at me and said, “No, what I mean is that psychiatry is finished. L. Ron Hubbard has ended psychiatry.”

I said, “Really?”

“Ron is going to win the Nobel Peace Prize.”

And I said, “Wait a minute. I’m sorry, Mr. Campbell, but you’ve lost me. You have to understand that I’m out of Madison Avenue. Outside of the normal networks I don’t know what the hell’s going on.” And I thought, Or in this tacky little office, in this tacky little room, and this guy is full of it.

He said to me, “Would anybody who ended war with the Peace Prize?”

I said, “Sure.”

“L. Ron Hubbard has ended war.”

“Wait a minute, you’ve lost me. How?”

“Dianetics.”

“Honestly, Mr. Campbell, I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

And he said, “Here. Read this.”

“Here and now?”

“Yes.”

“Couldn’t I take a set of galleys home with me?”

“No, no, it’s the only set I’ve got.”

So he’s going about his business, talking to his secretary and whatnot, and I read the first galley and said to myself, “I can’t make any sense out of this mishmash,” so I turn to the second galley and I start to skip over a little, then a little more, but I figure this Campbell looks like a pretty shrewd guy, so I allow enough time for each galley, then I go on to the next one — and hell, there must have been 12 to 15 of these galleys, it was an enormous stack — and so I finished, put them on his desk, and he looks at me and says, “Well? Are we going to win the Nobel Peace Prize?”

And I said, “Well, I can’t tell…but it was very interesting, very interesting concepts behind it…I don’t know. If I could read more of it, I…”

“No, no. The galleys are being rushed in right now.”

“Well, I don’t know.”

And he said, “Look, you’re rejecting it.”

“No, Mr. Campbell, I…”

“That’s alright. People always reject new ideas.”

“Not me, Mr. Campbell. I’m like a monkey; I’m always curious about these things.”

And he said, “No, no, no.” He wouldn’t listen to me.

So we went to this tacky little lunchroom. It had no windows, four walls, and people were screaming their orders in, and we finally got our orders in and Campbell all of a sudden turns to me and says, “You know, we can remember…we can remember all the way back to the fetus.”

“Back to the fetus?”

“Ah, yes. The fetus remembers.” And he stands up over me and says, “You can clear yourself. Put your mind back…think, think…remember, remember…when your mother tried to abort you with a button hook and you’ve never stopped hating her!”

And I was really shaken. I said to myself, Oh dear God, don’t let me laugh in his face. And the only way out of it was to agree, so I said, “You’re absolutely right, Mr. Campbell, I can’t go through with it, the emotional scars are too strong.” He sat down and we went on chatting.

But all he wanted was all the Freudian things taken out of the story so it wouldn’t get in the way of the new Dianetics. Of course, when “Oddy and Id” was reprinted I went back to the original. But that was the one session I had with Campbell and it was the last. That guy was a maniac!

But both of us were arrogant — and I am arrogant, a know-it-all — the only difference between us is that I can laugh at myself, but he couldn’t. That’s the big difference. The only thing that saves me is that when I often see myself behaving like him I say to myself, “C’mon, kid, who are you kidding! Get off it.”

TANGENT: How does your humorous side affect your fiction?

BESTER: I don’t know. I have a funny attitude toward life; I have a funny attitude toward people and myself. I laugh at other people. I laugh with them, I laugh at myself. And if it find its way into the stories then fine, great.

I never try, deliberately, to write a “funny” story. I just try to write a story. When The Computer Connection first came out in Ben’s magazine, people would say to me, “Jesus Christ, this is as funny as they come, Alfie.” And I said, “You find it funny? Well, gee…” It didn’t hit me as a comedy when I was writing it. I didn’t try to be funny.

TANGENT: How do you get along with people with no sense of humor?

BESTER: I can’t. I forget’em. I find myself trying harder and harder to get a laugh out of these cats and I end up feeling gauche, awkward, and its gets worse and worse and I make a goddamned fool out of myself, and it’s a real mess…. So, I just don’t worry about them anymore.

TANGENT: In The Stars My Destination, at the scene where Gully Foyle goes through a synesthetic experience– What led you to deal with synesthesia back in the early 50s before it was on everyone’s mind with the psychedelics in the 60s?

BESTER: After I wrote that, and it was published, I got dozens and dozens of calls asking me, uh, “We know you’re into the psychedelic trip–” And I said, “Psychedelic? What’s that?” And they explained to me about LSD and what a psychedelic trip was–and now it comes into focus.

What happened was, quite simply, when I got onto the psychiatric kick I read every damn book I could find. Criminal psychiatry, pathological psychiatry, and stuff like that. And all for one purpose: story ideas, for gimmicks in my stories, is all I was after. And I must have found hundreds of them and listed them all. But I ran across this one, a description of it and everything, which does occur but is rare in patients. FLASH! WOW! This could be marvelous, visually.

[Ed. Note: Alfie gestures and says] …END PART ONE… [He resumes, after taking time to take a few swallows of his drink and catch his breath, as do we. After this brief break he resumes with] …PART TWO:

[Ed. Note: Alfie gestures and says] …END PART ONE… [He resumes, after taking time to take a few swallows of his drink and catch his breath, as do we. After this brief break he resumes with] …PART TWO:

When I was writing The Stars My Destination I got three or four chapters into it and I broke down three times and couldn’t write any further. So I had moved to Rome, and it was very hard to gain back my lost momentum, my enthusiasm, after the third time around, and I was writing very cautiously, and I remember very distinctly getting into a conversation with a young Italian director who spoke about as much English as I did Italian; we had to draw pictures for each other…and we were talking about the things they would not let us write, or do, and I described to him synesthesia, which I had wanted to do for a long time as a television script because it’s a visual thing, and how furious I was because they’d never let me touch it. It was too original, nobody would understand, the budget wouldn’t understand, all of that nonsense; and while I was describing it to this director it hit me like Christ Jeezus on a raft! That is the finale of the book! That’s what holding you up, old Alf! You don’t know where you’re going. Now you know where you’re going–go man, Go! And I hotfooted it back to the penthouse I had, and I really buckled into it, because I had that to look forward to.

I’m of the school that says you start with an earthquake and build to a climax, and I had not realized that I did not have my climax in mind, and that’s what was holding me up.

TANGENT: The logical extrapolation from the reality of synesthetic experience seems for me to be this: Does the world create the mind (modern philosophical materialism) or does the mind create the world (Kantian and/or Berkleyian idealism)? Do you see what I’m getting at?

BESTER: I see what you’re saying. I’ve thought about it very often. I never raised that issue in the book, but, I will tell you this: in the book I’m working on now I am attacking that issue square on. I came up with — not a solution to the problem — nobody is ever going to be able to solve that one; but I have come up with a story pattern which involves that, and is it WILD! I’m terrified that I’m not good enough of a writer to handle it.

TANGENT: Maybe you shouldn’t talk about it.

BESTER: I intend not to, if you’ll forgive me. I don’t want to because there are many motivations for writing. One is to do a professional job, to do justice to an idea in a story…but way back but very powerful, is this: “OH, THE SONS-OF-BITCHES, HOW SURPRISED THEY’RE GONNA BE WHEN THEY READ THIS!”

end

Interview and Alfred Bester photo copyright © 1977, 2011 Tangent/Tangent Online and David Truesdale. All rights reserved.