Special Double Review

Albedo One #39, early 2011

“Frogs on my Doorstep” by Annette Reader

“The Horse Shoe Nail” by Mari Saario (Reprint)

“Hothouse Flowers” by Mike Resnick (Reprint)

“Eskragh” by Martin McGrath

“Partly ES” by Uncle River

“Grappler” by JL Abbott

Reviewed by Kevin R. Tipple

Albedo One is a print science fiction, fantasy, and horror magazine published 2 to 3 times a year (though subscriptions are for four issues). It is published in Dublin, Ireland. There is also a new feature on the Albedo1.com website titled “Albedo 2.0” that showcases new stories and other content that is exclusive to the website.

After an extensive wide-ranging multi-paged interview with author Mike Resnick, the magazine moves on to the stories. The four original stories are of varying quality and, at times, ones that don’t seem to really fit the stated intention of the magazine.

The fiction opens with their 2009 Aeon Award Winner, “Frogs on my Doorstep” by Annette Reader. Fifteen years ago when Jack was five, his three year-old sister Ellie vanished from their very small backyard. She was there and then suddenly was gone. The disappearance of a child is every parent’s nightmare and the disappearance of Ellie devastated the Shelford family.

When the days stretch into weeks and months, the child rarely comes back home at all and certainly not back alive. But, Ellie did come back once, shocking everyone in the family. Jack is praying she can do it again and get it right this time.

An interesting tale about parallel realities and other dimensions that works for the most part. Despite a couple of twists thrown in, there isn’t really anything new here as these sorts of things have been done many times before. Considering the use of the TV personality Oprah to set the story up, the work is dated, as Oprah has moved on and in a different direction with her career.

Author Martin McGrath used a tragedy in his own life as inspiration with “Eskragh.” Family tragedy is also at work in this tale. No parent expects to live longer than their child. Unlike the family in the preceeding story, Thomas’ father knows what happened to Thomas. He just never got the chance to bury his son’s body.

His son and several others had gone swimming in a local lake in Northern Ireland. Six went in and at when all was said and done only five came out. Thomas went missing and presumably drowned in the deep waters of the Eskragh leaving one final memento behind.

I‘m at a complete loss as to why this tale was published in the magazine. Despite the fact that the story is well written and is good one, it does not remotely meet the intent of the magazine. There is no science fiction or fantasy component. It could conceivably be argued by somebody that it contains horror in the death of a friend as well as in the slightly ambiguous ending. However, if one were to accept that premise, then it follows that nearly any story in any genre would meet the requirement as would nearly everything in any magazine or newspaper. Don’t get me wrong. It’s a good story. It just does not fit the stated mandate of the magazine.

The same is true of “Partly ES” by Uncle River. According to the sidebar introduction, this is a work by a returning author and one can’t help but wonder if that was the primary criteria, though there are a couple of very small science fiction pegs.

Set in Partly, New Mexico located on the Continental Divide and in a time where stringent gas rationing is in effect with Homeland Security in charge of nearly everything, the story tells the tale of the day-to-day existence of a number of residents in the small town. It begins with the interruption of a small dinner party with a call for emergency assistance. It is two days before Christmas and the locals have to rely on fellow resident volunteers to provide any type of emergency services.

This police procedural style story moves on page after page and day by day as readers discover far more than they care about the locals and their back stories. These are isolated people in an isolated area where their only outside contact is pretty much limited to faceless Homeland Security workers manning distant checkpoints and radios. Politics at the local and national level are prominent in this story, that eventually whimpers to a stop having told a tale with no meaning or purpose.

“Grapple” by JL Abbott is another excessively worded story that at least fits the fantasy genre and has a point at the end. It just takes decades to get there in a story full of unclear symbolic meaning and constant repetition.

Set in the Sacramento Valley of California, it begins with a dying woman’s vision. The Maidu people listen as Circle of Stones explains her future vision, and what will happen. In her three-part vision she explains with her last breaths how they can prevent their people from being wiped out.

Eventually the second part, by way of “a deformed man made of dust [will] bring death” comes to pass. Known as “Grappler,” he has two legs and a solitary deformed arm that hangs from his chest. He is monstrous, and the young warriors who by now don’t think much about Circle of Stones and her visionary warnings, make fun of him until one of their own dies a gruesome death before their very eyes. After killing the young warrior, the Grappler drags his widow into the brush to be his wife where she is heard screaming before all is quiet.

Years and decades pass as the people of the Maidu are born, live, and die. Every so often the Grappler returns. He kills again and again and finally stops when the third vision comes to pass.

Along with the gruesome violence across generations, there is some heavy-handed lecturing about sticking with tradition and knowing and respecting the wisdom of your elders. It is when that knowledge of the old ways and the prophecy is lost because the times have changed that the final vision comes to pass. The story takes forever to get to that point, which is reminiscent of a repeated metaphor in the work. The people of the Maidu believe a snake continually consumes his own tail to create the seasons. Reading this ten page story felt like much the same thing as it went on and on with constant repetition of earlier events. The names changed, the manner of death changed, what was done to the women the Grappler chose to be his wives changed, but the story staggered on far too long before finally bringing itself and the fiction section of this magazine to a close.

A couple of pages of reviews bring this 63 page print magazine to an end. Up and down in terms of quality stories that meet the stated mandate of the magazine, I was not impressed with it at all. This was my first experience with it, so I don’t know if this is a representative issue in terms of the fiction or not.

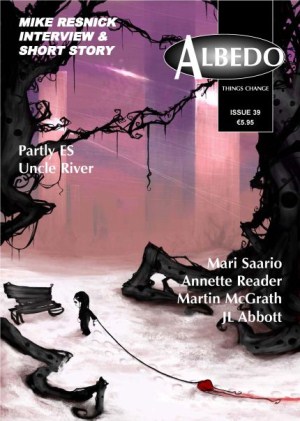

It is clear that the quality in this issue varies all over the place with several stories having either no connection or a very tenuous one to any concept in the science fiction, fantasy, or horror genres. Despite the striking front and back covers, “Ireland’s Magazine of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror” was a disappointment.

Albedo One #39 (second review)

Albedo One #39 (second review)

“Frogs on my Doorstep” by Annette Reader

“The Horse Shoe Nail” by Mari Saario (reprint from the Finnish, 1st English appearance)

“Hothouse Flowers” by Mike Resnick (reprint)

“Eskragh” by Martin McGrath

“Partly ES” by Uncle River

“Grappler” by JL Abbott

Reviewed by Caroline E. Willis

“Frogs on my Doorstep” by Annette Reader won the 2009 Aeon Award for Short Fiction, with good reason.

The story is mostly told by Jack, a boy whose sister disappeared from their backyard when she was three, and reappeared a year later, when she was eighteen. Jack was six when Ellie came back, and only he believed her story – she had Kermit. Kermit was Jack’s favorite toy, and despite the violent years that Kermit had experienced, it was still recognizably his. Jack and Ellie’s parents couldn’t believe, of course, but Jack did.

The conclusion of “Frogs on my Doorstep” almost isn’t a conclusion. Instead, it ends on a reverberating note that echoes and re-echoes long after the story itself has ended. Reader has crafted a superb piece of work.

“The Horse Shoe Nail” by Mari Saario is a fantasy story set in one of those places that acts as an intersection between worlds; specifically, the old smithy in a little village in Finland. In that little village is a girl, Alice, and her drunken father, and almost enough books for her to hide in.

Alice’s grandfather, her father’s father, was the smith; and one summer day she retreats to the smithy to read and finds two travelers, Agenor, and Reynard the Golden. They are messengers, and the fate of kingdoms depends on them getting though. It is, as Alice says, like something from a tale.

“The Horse Shoe Nail” does not tell the story of these men, though; it tells the story of Alice’s life, as it is affected by this intermittent magic. The narrative jumps decades, starting in when Alice is a girl, passing through her late teen years, stopping when she has become a woman and a mother. Alice’s life is very real, for all of the fantasy involved, and the pathos made me cry in spite of myself.

“Eskragh” by Martin McGrath is nearly a haiku. McGrath’s story is the shortest in the issue, and he makes every word count. “Eskragh” is a slow horror piece–the kind in which the story ends without ever finding out if the monster is real.

The narrator’s friend, Thomas, disappears one sunny afternoon while they were hanging out at Eskragh Lough. “Eskragh isn’t a big lake, but it’s deep,” the narrator says. That line repeats throughout the story like a chorus, or the lapping of waves. The timeline of the story also loops back on itself, rocking back and forward through time to the ultimate conclusion of events.

Horror can often be about the ways in which the human mind reacts when confronted with something outside its understanding of the world–an event outside normal causality. “Eskragh” uses that horror to communicate the emotional weight of loss without explanations.

“Partly ES” by Uncle River is set in the near future in Partly, New Mexico. The story follows Golan, an elderly member of the rather elderly volunteer-run emergency services department in Partly. The town is nestled high on the continental divide, and the story takes place before and after Christmas, when snow and ice keep the volunteers busy.

River focuses his story on the lives of the volunteers; “Partly ES” reads like the stories grandparents tell when their grandchildren ask them,

“What was it like?” The world exists only as a backdrop to the people, but that world has hints of very scary things in it. Partly, on the other hand, is simple; normal people, mostly good if a little selfish, living their lives. The main character, Golan, responds to a few calls, has Christmas dinner with a friend, and gets delayed on a non-life-threatening ambulance run by some unexplained activity in the desert. “Partly ES” is simple, detailed, and rich.

There is one tiny error that jarred me–an American character says that she will go back to get a torch, rather than a flashlight. Albedo One is an Irish publication, so this may have been a localization decision, but as an American reader it catapulted me out of the story. However, the strength of the rest of the piece soon drew me back in, and “Partly ES” is well worth a read.

“Grappler” by JL Abbott is by far the most plot-driven story of the issue. It follows a standard ghost story format, with the boogey monster making two attacks before finally being defeated a third time. The monster, in this case, is Grappler. He appears in the form of an old man with shadows for eyes and one withered arm that hangs down from the middle of his chest.

Ghost stories are an oral tradition, and Abbott writes this one in that tradition, with all the varying repetition that implies. He uses the genre conventions with skill, so that rather than being bored, the audience feels the creeping horror of knowing just what evils will befall the characters before they do.

Another ghost story tradition Abbott taps into is the mutilation of women. That’s what Grappler is after; each time he comes to the village, he challenges the men for a wife. A man dies, and a woman is taken away. The woman always returns, mutilated and broken, and is left to die by the fearful villagers. The men in this story die warrior deaths, but the women are tortured, sometimes for years, before being returned to suffer and be denied help by their former families.

It is horrific in as many senses of the word as I can think of.

That is something to think about before reading, if you are the sort of person who might be triggered by that kind of content; Abbott pulls no punches, and even Grappler’s eventual defeat is not cathartic enough to leave you feeling quite safe at the end. That is another ghost story trope, of course; there is always room for a sequel. Abbott demonstrated mastery of his craft in putting this tale together, but if I could scrub the memory of it from my brain, I would.