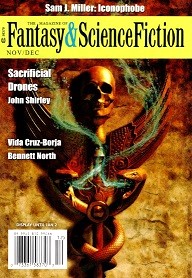

Fantasy & Science Fiction November/December 2022

Fantasy & Science Fiction November/December 2022

“Sacrificial Drones” by John Shirley

“Optimist Cleaver’s Last Transmission” by J.C. Hsyu

“Crypt Currency” by Sara Ellis

“To Carve Home in Your Bones” by Aigner Lee Wilson

“Though the Heavens Fall” by Louis Evans

“The Shotgun Lucifer” by Bennett North

“Child of Two Worlds” by Vida Cruz-Borja

“Iconophobe” by Sam J. Miller

“Skin of the Beast” by Alexander Flores

“Santa Knows” by Jo Miles

“Water Music” by Michael A. Gonzales

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

From this issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction Tangent reviews eleven new pieces consisting of seven works of short fiction and four novelettes. The issue does contain some works this reviewer would have considered flash fiction, but they appear in the table of contents as “poems” and Tangent‘s official position is that it does not review poetry. Alas. On the upside, the proportion of stories that can be recommended in this issue is high, easily exceeding the one-third threshold the reviewer ordinarily sets as a benchmark. There’s something here for fans of comedy, horror, drama, fantasy, science fiction, and fairy tales—and still the reviewer is surely missing somebody. Worth reading.

Sara Ellis‘ “Crypt Currency” is a first person urban fantasy narrated by a self-employed purveyor of magic ingredients supplied largely by grave-robbery. Strong humorous elements repeatedly appear, but the dark characters, jobs, and problems in the “Crypt Currency” world balance them for an excellent roller coaster. The villains are properly villainous, and the good guys’ cause deeply just; the stakes escalate quickly on a rush job and things fall apart wonderfully. Ellis sets expectations so that the story’s various reversals feel consistent with the world. “Crypt Currency” delivers a grand slam home run conclusion the reviewer can’t resist saying you can take to the bank. Bonus points for a character paid crypto to rob a crypt.

John Shirley‘s science fiction novelette “Sacrificial Drones” teases near-to-hand technological utopia but dashes hope in tragedy. Told in close-third person, it opens over the protagonist’s shoulder witnessing the murder of a family in the middle of the 20th century. It’s an effective scene. The rest of the story is related from the perspective of a scientist in 2049 whom the protagonist hopes to recruit to support his own high-tech projects. Following the scientist’s perspective, the reader may reasonably expect her to have the highest stakes and to make the story-shaping decisions, but this isn’t borne out. The time she spends deciding whether to trust him feels crafted to support a workplace romance: her friends gush about how gorgeous he is, and reveal that in addition to being a zillionaire with the resources to rejuvenate himself into a 30s-ish body at will, he oozes virtues such as having single-handedly but anonymously put a halt to the dog-meat industry in Asia. Few of the virtues ascribed to the protagonist affect the plot; they’re color, delivered by various trusted sources, to signpost for the reader that the protagonist is a solid catch or, at least, a Good Guy™ on whom the characters and their world and (most importantly) the reader can depend. Rather than hook the reader with a specific problem or some emergency, “Sacrificial Drones” skips from the witness’ Disney-style orphaning tragedy directly into what appears a low-stakes drama involving a single woman keen to improve the word with her research, and her encounter with an apparently-forever-young philanthropist. “Sacrificial Drones” feels like it delivers too much good news about him: he seems to solve too many of the POV character’s problems not to secretly be a disaster in the making. Maybe if the good deeds were byproducts of an unfolding plot they’d feel more natural, rather than feeling like carefully-placed strobes along an airport runway. If the reviewer’s mind hadn’t unintentionally rebelled against the planted evidence that proved the protagonist’s virtues, the ending might really have felt like the tragedy. Often when a POV character turns out not to be the protagonist, it’s the result of a story’s commitment to a first-person point of view (e.g., Jim Butcher’s Ghost Story is full of scenes in which the incorporeal narrator can do little more than observe the scene protagonist). In a story told from third person it’s unclear how the reader should benefit from having the story climax related from the point of view of a character who not only has no access to the protagonist’s inner thoughts and deliberations, but is physically absent for safety reasons. The reviewer speculates that the reader is expected to hope the scientist will build a future with the gorgeous and virtuous multibillionaire hero, and therefore reel with horror when his tragic decision leaves her instead with merely funding for her life’s research. The reader isn’t made to look very hard at stakes beyond those of the researcher whose point of view is being followed. In order to accept the legitimacy of the protagonist’s framing of his problem, the reader must believe the statements of people talking about the decision, or the protagonist in recordings. This feels so distant from the access one might have through thoughts of the tragic protagonist that it’s difficult to understand why that character was given the tragic choice instead of the POV character (or why the POV character wasn’t changed to follow the character with the higher stakes). Another reader, more willing to accept a description of a recorded statement at face value, might successfully buy into the climactic decision and thereby better appreciate its aftermath. The reviewer could not.

J.C. Hsyu‘s first-person short story “Optimist Cleaver’s Last Transmission” is a one-last-job revenge plot dystopic science fiction mystery. Fans of Cyberpunk will appreciate the grimy world of fee-for-service couriers trading on their reputations to risk their lives for pay to deliver messages on behalf of (and to) anonymous strangers in a post-apocalyptic San Francisco. Hsyu’s effective use of longstanding traditional story elements is particularly outstanding. The reviewer is reminded of Jim Butcher’s answer to a convention fan question about avoiding tropes: Why would you want to avoid them? They’re tropes for a reason. Executed badly one might be dismissed as cliché, but done well each can leverage the entire power of the idea that made the element so attractive that artists have been drawn to execute it so many times that it has become a recognizable trope. Hsyu weaves so many well-executed story craft elements into the work that it’s hard to pick examples. Everything – the revenge plot itself, the One Last Job scenario, a couple of “What kind of name is that?” challenges—has been artfully formed from rough clay into a masterwork. It’s a solid story and a fun read. Nobody with a yen for Cyberpunk should miss “Optimist Cleaver’s Last Transmission.”

Aigner Lee Wilson opens the third-person multiple-point-of-view novelette “To Carve Home in Your Bones” on an injured wreck victim being found by her teammates. The tale mixes ideas from shipwreck disasters, the pandemic, and perhaps zombie fiction to narrate injury and flirting and suicide and mercy killing and, of course, anticipation of the next round of disaster. It’s a dark story set in a dark world, but it doesn’t immediately telegraph a specific genre; identifying the genre seems to turn on what a “faerild” is and whether it’s a natural parasite or a fantasy beast. The reviewer leans toward Fantasy but it doesn’t matter: the story’s genre is horror. If you like horror, this one’s for you.

In “Though the Heavens Fall” Louis Evans presents science fiction set in deep space among intelligent starships whose sensors and propulsion depend on physical principles not yet known to science. Evans presents a universe whose varied inhabitants, who may lack a common culture and may share no common language, may interact using a Protocol that enables willing participants to use their propulsion systems to make a high-stakes interaction from even such pedestrian occasions as a dinner party or a trade opportunity. Since the Protocol gives rise to the story’s stakes, and is revealed immediately, the reader might as well understand that while the Protocol facilitates interactions, it does so at life-or-death stakes: no ship entangled in the Protocol can leave without the same kind of mutual assent that created it. Since it turns out all the story’s characters actually do have a common language, and there is no need to join a suicide pact to interact with one another in space, it may be more appropriate to view “Though the Heavens Fall” as a fable or parable than a thought experiment in how the future would look if the technology in the story existed. And the uses to which the Protocol is put—the specific rituals revealed at the story’s various junctures and the grievances raised about violation of their rules—seem to prove that the Protocol isn’t actually for strangers that can’t communicate because they have no shared culture, but is a class of interactions that depends for its use on sharing an existing culture about the Protocol and the specific rituals that can be invoked by its users and the peculiar rules of each ritual. Having said that, one may easily look at the story as a parable about human relations and the expectations of different social groups as they interact with one another, and draw the conclusion that regular civilized interaction could be likened to strangers who have joined in a life-or-death ritual just to share a continent or a nation with one another forever or for a time. The idea that different groups have radically different ideas about what constitutes fairness and reasonableness ought not be a stretch for a reader from this world to believe, nor the idea that groups will willingly threaten death or even mutual destruction if they don’t get their way in some conflict that needn’t actually involve death threats. The idea that one can in such a world find community and purpose by advancing justice is a heartwarming idea and may by itself be fuel enough for a reader’s enjoyment. Likewise, the idea that selfish and indignant oppressors might pretend to demand the benefit of rules while refusing to suffer any cost to live in a world full of rules may resonate with a lot of readers, who may at such villains’ demise take the kind of pleasure one finds in a well-crafted revenge plot. It’s not obvious to which category of reader the story should be recommended—it doesn’t posit a credible science fiction world, but it certainly spins a parable whose good guys and bad guys are readily identified and whose fates are easy to celebrate. The reviewer suggests that “Though the Heavens Fall” should be viewed not so much as science fiction about alien communication but more as a space fable about justice and just desserts.

Bennett North‘s “The Shotgun Lucifer” is a science-fiction short story set in a place where humans have evolved echolocation as their primary sense for detecting objects at range. Since quite a bit of the story’s appeal comes from revelations regarding the setting and the characters’ senses, it’s difficult to discuss facts about the world without risking spoilers. Told in third person, it follows a man acting as a caravan guard while he attempts to escape a community where he is wanted. Naturally, the escape goes badly and the result reveals the abilities and values of both the main character and the woman he decided to rescue from his own pursuers. The protagonist’s heroic choice doesn’t directly save anyone, but his demonstration of character results in his being rescued in return. Some editors dismiss stories that depend on concealing from the reader things that would be obvious to the reader if the reader were present, but this reviewer takes the view that if the point-of-view character would not choose to remark on something—whether because that character would be unaware, or because the character would take the fact or circumstance for granted to such an extent as to render it unnecessary for comment—then it’s fair game for springing on a reader late. North does exactly this, and it works precisely as intended. The climactic confrontation includes a Riders of Rohan moment that presents a delightful surprise precisely because the protagonist doesn’t sense things the reader would. This story offers hard SF for those who love it, and is a fun read to boot.

Set in the shared fantasy world of Hinirang which the author shares with Dean Francis Alfar, “Child of Two Worlds” by Vida Cruz-Borja is a coming-of-age quest. A reader with existing familiarity with Hinirang might be able to notice recurring characters or appreciate references to related works but, alas, this reviewer cannot. It’s worthwhile to be introduced to Hinirang: natural and magical perils and creatures from folklore—all with Philippine flavor, which some readers may discover is itself a new thrill. Much will seem familiar to readers of fiction inspired by other folklore, such as supernatural creatures bound by rules and keen to make bargains with witches about children not yet of age, and the utility of wearing clothing inside-out to repel certain inhuman threats. In about 7500 words, Cruz-Borja manages to relate the life of Adelfa from her Disney-style abandonment as an orphan, through an upbringing under two different magical traditions, and to an ordeal through which she seeks to throw off the yokes of two competing mistresses to choose her own fate. It’s a lot of distance in a short story. It inverts the trope of a young man winning the hand of a princess; “Child of Two Worlds” depicts a young woman overcoming obstacles to free a lost nerd explorer whom she hopes will expose her to a larger world than the fiefdoms of her competing mistresses, thereby enabling her to find her own path in the world. She doesn’t want protection or to settle down with a spouse, she wants to keep learning. It’s a worthy goal and her victories are well-suited to a culture-hero style clever victor.

Sam J. Miller’s third-person fantasy short story “Iconophobe” is set in an alternate 1979 (a year after the mass-suicide at Jonestown) in the aftermath of a cult’s large-scale suicide bombing of film processing infrastructure around the world. (Yes, in 1979 photographs required an enabling technology called film. No, no, it’s true. I saw it myself. The chemicals involved in the process explain the color palette of images from the Seventies. I would not make this up. Every photo chemical process ever invented involved silver, an element once also used to make mirrors.) The main character, an author/reporter, thrills at the news the cult has blown itself to bits: his midlist novel about the cult is about to hit the bestseller list, and he needn’t fear them if they’re all dead. Alternating between an anxious, unhappy present, and a flashback timeline while part of the cult, “Iconophobe” lays out the emptiness of the protagonist’s life, the wild doctrines of the anti-photography cult, and the protagonist’s guilt over the lover he abandoned with the cult. Descriptions of sex and nudity emphasize the narrator’s vulnerability and emotional connection while exposing his journalistically inappropriate relationship with his subject matter. The difference between the cult’s rituals as depicted in the author’s book (exotic but vacuous) and the author’s own experience (simple but profound) show the protagonist isn’t so much reporting on the cult as he is trying to convince himself, or perhaps the people around him, that he’s normal and the cultists are mad (and maybe sell books). The dark ending suggests the cultists understand more about the world than the supposedly sane. The climax is more in the nature of a reveal than a confrontation in which a protagonist must make a hard heroic choice, and the suggestion the main character is not in control of his life supports the dark conclusion. If you like dark, creepy horror fantasy you will want to read “Iconophobe.”

Michael A. Gonzales’ short story “Water Music” is an urban fantasy featuring a river cryptid with a taste for sax players. Ensorcelled musical acts date back to the dawn of urban fantasy in Emma Bull’s War for the Oaks, and as an element represent virtually a hook by itself. Unlike rigid magic systems that seem to operate like a vending machine (“accio broom!“), much of the magical music one finds in Fantasy seems instead ethereal, limitless, and hard to pin down with rules. “Water Music” features the cryptid Monongy, known to live in the Monongy River that flows north into the protagonist’s hometown Pittsburgh, and beside which the protagonist grows up practicing his horn and, as it happens, making a fan of the cryptid. Pittsburgh isn’t the same kind of music market as New York, though, so he’s lured away for work. Since the protagonist doesn’t face his fate in a confrontation that culminates in a character-identifying climactic decision, the story has a structure akin to a just-desserts fairy tale in which the main character’s largely passive behavior causes powers beyond mortal control to deliver judgment.

Alexander Flores’ short story “Skin of the Beast” is an inverted beast-spouse fairy tale in first-person. Under 2,000 words, it’s a quick delight. The story includes a little poem the beast sings to its mate at the beginning and the end, like a preface and a coda. This conveys a feeling of coming full circle when Flores juxtaposes the dark ending with the comforting feeling from the repeated verse; it’s executed so well the effect is poetry itself. If you like dark justice, fairy tales, story inversions, or liberation stories, “Skin of the Beast” may be for you.

Jo Miles‘ “Santa Knows” is an urban fantasy comic revenge plot set off by a tech surveillance profiteer destroying childhood with an app-driven, spycam-fueled, activity-monitor-verified analysis of everything every child can be caught doing wrong. The delightful premise is the hook: someone in this world actually reads Santa’s letters and determines that sucking the fun out of kids’ lives is naughty. There are some lines so delicious the reviewer is tempted to quote them, but the reader should be allowed to discover them personally (with or without a fist-pump). Unlike hardened adult revenge plots (Sudden Impact, John Wick) that culminate in brutal murder, “Santa Knows” delivers consequences at a grade-school level that’s both well suited to the story’s agent of justice and entertainingly humiliating for a tech tycoon. Good fun.

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.