The City of Baal: Adventures in Colonial Africa by Charles Beadle

Edited and with an introduction by John Locke

(Off-Trail Publications, 2007)

“The Cave” (Adventure, October 3, 1918)

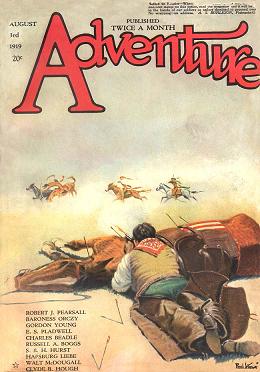

“The Tree of Life” (Adventure, August 3, 1919)

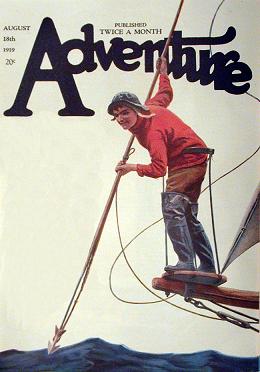

“The White Frog” (Adventure, August 18, 1919)

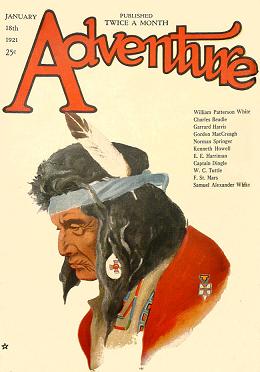

“The City of Baal” (Adventure, January 18, 1921)

“Buried Gods” (Adventure, September 3, 1921)

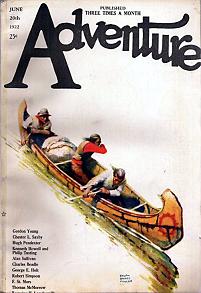

“Gifts of Diamonds” (Adventure, June 20, 1922)

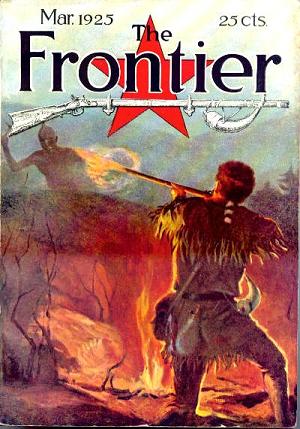

“White Magic” (The Frontier, March 1925)

Reviewed by Dave Truesdale

The nostalgic resurgence of interest in the pulp magazines of yore (1896 to roughly the early 1950s) was formalized with the first Pulpcon in 1972. Interest has increased geometrically since then, with any number of small press publishers reprinting stories from all genres: detective, mystery, spicy mystery, weird horror, science fiction and fantasy, war, gangster, romance, superhero, and rousing adventure stories set in all parts of the world–from Africa to the Amazon to China and all points in between. The interest shown for the pulp experience generated by Pulpcon has led to other conventions catering to rabid pulp magazine fans. In its 11th year, Chicago hosts the Windy City Pulp and Paper Convention, and Columbus, Ohio is in its 3rd year of hosting Pulpfest (the reincarnation of Pulpcon, which ceased in 2009). And there are others scattered throughout the country.

The small press pulp reprint publishers focus on different aspects of the early pulp magazine experience according to their own interests (publishing either in trade paperback editions or more expensive and lavishly produced hardback editions). Some concentrate solely on SF/F authors whose stories first saw print in the pulps. Some reproduce expensive facsimiles of individual issues of various pulps–perfect in every detail from the originals. A few publishing houses are more eclectic, producing trade paperback volumes showcasing collections from all the early pulp magazine genres. Most of the stories are in the public domain, making the acquisition of rights a non-issue. Nevertheless, much work and many hours of research are needed to rediscover authors’ stories (often scattered over a plethora of pulps spanning several decades), and then they are scanned, edited, and packaged. A labor of love, but to the avid pulp fiction collector worth every penny, as a fair number of stories have hitherto never been reprinted from their original magazine appearances from nearly 80 to 100 years ago. While prices from the top end, lavishly produced hardback or facsimile publishers run in the neighborhood of $30 to $40, the ballpark average for a nice trade paperback runs anywhere from around $14 to $20. These affordable trade paperbacks usually sport a photo of the author (when available), and at least something of an introduction by the editor, with a brief history of the author and the work under consideration. Original publication sources and dates are always included as a matter of course. As a relative newcomer to these small, independent pulp magazine reprint publishers I have yet to be disappointed in any of their publications.

A prime case in point is publisher John Locke’s Off-Trail Publications. John was kind enough to send along several of his books, one of which we’ll take a look at here.

Off-Trail Publications (OTP) specializes in the obscure. Locke explains the philosophy behind his enterprise:

“I called the imprint Off-Trail (i.e. out of the mainstream) because I specialize in obscure pulps, authors, stories, etc., material that in many cases has not been examined since original publication. I try to provide as much history with the stories as possible; I feel that the complete package is stories plus author biographies plus magazine history plus genre examinations, etc. One would hope to be unearthing forgotten treasures at every turn–and much of the stuff I’ve reprinted has been terrific reading. But many pulps turned out fiction at assembly-line rates, and some pretty gamey prose was the result. Sometimes the best history accompanies bottom-rung material–the complete package gives a broader view of the medium. As opposed to the typical best-of collection which cherry picks. I’m more likely to reprint a story that reflects the author’s personal experience than one which reflects his best work, for example. Or a story that illustrates a magazine’s change in direction; or shows borrowing from other media, or reflects current events.”

Which brings us to The City of Baal: Adventures in Colonial Africa by Charles Beadle. The collection opens with a thoroughly captivating introduction by Locke. To say it is complete would be an understatement. It goes back hundreds of years in its detail of the origins of European exploration, colonization, and exploitation, marking out the territories the Portuguese, French, Dutch, British, German, and others carved for themselves. Along the way we learn the various political intrigues of the time and what influences they contributed to how Africa was divided and why. We are also given instances of native African rulers and internal politics and their role(s) in dealing successfully or unsuccessfully with those who had invaded their homeland for profit. We learn factual details of the geography of the stories Beadle wrote–who himself was meticulous about such details, having fought in the Boer War (1899-1902), then traveled the continent extensively for years afterward as an odd-jobber and adventurer. Little is known of Beadle, though best guesses are he was born somewhere in the 1880s and died sometime in the 1950s–though evidence is sketchy at best and guesstimates are inferred from incomplete paper trails. After reading the introduction I felt as if I had passed an introductory course on the history of Africa, from its politics, its geography, its economic relevance, and its people–including the history of the slave trade, elements of which I was totally unaware. Almost worth the price of admission in and of itself. Locke places each of the stories in these various contexts, with excerpts from the stories and factual material produced at the time (newspaper pieces, period histories, letters from the author, etc.). By the time the reader finishes this historical immersion process the feeling is one of deep familiarity; at the least, the appreciation level of each tale skyrockets from the historical perspective gained via the introduction. It concludes with a full page black and white map of continental Africa of the time, which also helps in placing local story geography and other references in clearer perspective.

Of the seven stories, all but one are taken from the pages of Adventure, and range from 1918 to 1922. The seventh is taken from a 1925 issue of The Frontier. Several have little or no fantastical element to them as we use the term today, but are straight adventure stories fraught with various perils. “The Cave,” for instance (the shortest of the tales), has to do with the local witch doctors stirring up the natives and causing all kinds of deadly mischief. When one of the Rhodesian Mounted Police is sent to quash the uprising he becomes the hunted. Escaping into a cave he finds himself lost in its maze of small tunnels. After one harrowing experience after another (most of the story, of necessity, takes place in absolute darkness)–including the discovery of human bones–he is rescued by his mates, only then to discover a surprise only the light of day could reveal, and is the true cause of the injuries he sustained while in “The Cave.”

“The Tree of Life” begins with this:

“The Tree of Life” begins with this:

“A vein of platinum on a jade ring was the river Mfunyaballa flowing through the forests of the French Congo. Above the place of a thousand islands is a slight rise of ground like a furry tongue protruding from the cavern of the forests, brown with the huts of the village of Basayaguru.

“On a hot afternoon, when the only moving things were the scraggy goats, lazily scratching, open-beaked native chickens and chromatic lizards, a faint throb vibrated on the sulky air like the pulse of a distant drum.”

After this snapshot description of a hot, lazy afternoon we quickly change gears and are thrown into deadly intrigue involving Arabs and the ivory trade, a local native tribe at the center of it all, a would-be sacrifice to the Tree of Life for two captive Britishers, magical hoodoo, six holy maidens, and a strange, unpredictable potion upon which the very lives of the protagonist and his co-captive hang. The growing tension slowly mounts–ably aided and abetted by the intensely vivid description of the night jungle and its impending evil–as it looks as if there is no way out for the good Doctor and his companion. Atmosphere, danger, and magic. Great stuff.

“The White Frog” interjects an initial bit of humor into the collection as several Britishers sit around a campfire. One tosses a magazine he has been reading by campfire light and exclaims of the improbability of stories taking place only “in imagination.” Wry banter ensues until our storyteller is cajoled into telling a supposedly real story–not a flight of fancy. As you might imagine, the story eventually (but cleverly) centers upon a white frog–both symbolic and real as it turns out. The tale begins at a fort of the British South African Mounted Police somewhere in Central Rhodesia. It soon draws us in with black magic vs. white magic, the white frog as devil god of the mountain who invades men’s souls, and amidst further twists and turns slides into darker and more dangerous territory. Again, quite a page-turner.

“The White Frog” interjects an initial bit of humor into the collection as several Britishers sit around a campfire. One tosses a magazine he has been reading by campfire light and exclaims of the improbability of stories taking place only “in imagination.” Wry banter ensues until our storyteller is cajoled into telling a supposedly real story–not a flight of fancy. As you might imagine, the story eventually (but cleverly) centers upon a white frog–both symbolic and real as it turns out. The tale begins at a fort of the British South African Mounted Police somewhere in Central Rhodesia. It soon draws us in with black magic vs. white magic, the white frog as devil god of the mountain who invades men’s souls, and amidst further twists and turns slides into darker and more dangerous territory. Again, quite a page-turner.

“The City of Baal” creates a lost city tale much in the vein of A. Merritt, or when looked at in a different light, H. Rider Haggard. It is based on myth and sketchy evidence that the Phoenicians had traveled to the heart of Africa millennia earlier and had established themselves along with their gods. It contains all the trappings of such “lost civilization” tales: a forbidding and cavernous temple, a ruling religious class of priests subjugating the populace, lots of gems and other valuable booty, cannibals (!), the requisite scenes of skulking around the interior of the temple before the inevitable discovery by the bad guys, then the fights and flights, death and destruction, and a final tooth-and-nail escape with whomever is left alive. Good old Phoenician-inspired, lost-city (back in the day) rock and roll.

“The City of Baal” creates a lost city tale much in the vein of A. Merritt, or when looked at in a different light, H. Rider Haggard. It is based on myth and sketchy evidence that the Phoenicians had traveled to the heart of Africa millennia earlier and had established themselves along with their gods. It contains all the trappings of such “lost civilization” tales: a forbidding and cavernous temple, a ruling religious class of priests subjugating the populace, lots of gems and other valuable booty, cannibals (!), the requisite scenes of skulking around the interior of the temple before the inevitable discovery by the bad guys, then the fights and flights, death and destruction, and a final tooth-and-nail escape with whomever is left alive. Good old Phoenician-inspired, lost-city (back in the day) rock and roll.

The remaining trio of tales, “Buried Gods,” “Gifts of Diamonds,” and “White Magic,” provide thrills and excitement aplenty. “Buried Gods” has several unfortunate colonialists captured and thrown into a pit/cave, from which the stacks of bones they find are testament to the fact that no one has yet escaped their prison. How they survive and why they were left to starve form the crux of this harrowing tale.

“Gifts of Diamonds” opens with a Foreword (by a writer, no less) recounting the delivery of a package from the Office of the District Commissioner of the British Central Africa Protectorate, to wit:

“Gifts of Diamonds” opens with a Foreword (by a writer, no less) recounting the delivery of a package from the Office of the District Commissioner of the British Central Africa Protectorate, to wit:

“A writer’s mail-bag is usually supposed to contain rejection slips and bills, varied by way of breaking the monotony, by a check. But one morning, in 19–, among the aforesaid classical contents was a registered package which I naturally took to be a returned manuscript or a bundle of proofs.”

The writer discovers that the package contains a number of letters forwarded by the aforementioned District Commissioner. As the title implies, the letters have to do with diamonds, and our writer is drawn into the story head first. As the fascinating story unfolds in this epistolary sequence of letters spanning several years, so too is the reader drawn into its heart and soul, the lives of several people (a brother and sister most notably) and how the adventure of the diamonds has followed them through the years and affected their lives. As with all of the stories here, it pulses strongly with the very life-blood of colonial Africa, its sights, sounds, smells, dangers, tragedies and triumphs, and is brought to life as only one who has lived there could capture its exotic, bitter-sweet contradictions. I really enjoyed this one.

The final offering in this sterling collection is “White Magic.” In this one, the British South African Police are summoned to a nearby village to forestall a woman being executed for witchcraft. What they discover is not what they expect. Local superstition, a witch doctor with his own agenda, and various plot turns pepper this tale of murderous chicanery and local custom gone awry. Whether intended or not, it reminds one of the Salem witch trials, which shows that in more ways than we can imagine, human nature is really not much different from culture to culture, separated in time by centuries, or half a world apart.

The final offering in this sterling collection is “White Magic.” In this one, the British South African Police are summoned to a nearby village to forestall a woman being executed for witchcraft. What they discover is not what they expect. Local superstition, a witch doctor with his own agenda, and various plot turns pepper this tale of murderous chicanery and local custom gone awry. Whether intended or not, it reminds one of the Salem witch trials, which shows that in more ways than we can imagine, human nature is really not much different from culture to culture, separated in time by centuries, or half a world apart.

The book ends with a Glossary of terms and Place Names. I usually hate these things because they detract from the flow of reading. One can usually figure out what a foreign word means through context, anyway. But this time I took a shot at it. Before long I hardly needed to consult the glossaries at all, much to my enjoyment. It was worth the effort, quite painless, and I came away much the richer for the experience.

The City of Baal: Adventures in Colonial Africa was an educational and entertaining read. The erudition publisher Locke shows in his exhaustively researched and penned biographical and historical introduction is matched only by his attention to detail, thorough knowledge of his subject, and careful selection of stories. I heartily recommend this collection.

The City of Baal: Adventures in Colonial Africa by Charles Beadle; edited and with introduction, map, and glossaries by John Locke.

(Off-Trail Publications, 2007, 240 pp., tpb, $20 US)

While Off-Trail Publications doesn’t appear to have its own website, one can easily order the book through Amazon.com here. Or order the book directly using this address:

OFF-TRAIL PUBLICATIONS

2036 Elkhorn Road

Castroville, CA 95012

For those with even the barest hint of interest in the pulp magazines and/or anything associated with the pulp experience, I point you to the most complete, up-to-date watering hole I have yet to find. The website is Coming Attractions, and if you’ve any interest at all in this broad and ever-expanding area of pulp nostalgia, you’ll find yourself bookmarking at least a handful of wonderful websites, including dealers offering more of John Locke’s Off-Trail Publications titles.