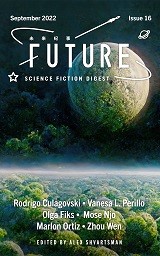

Future Science Fiction Digest #16, September 2022

Future Science Fiction Digest #16, September 2022

“Liz’s Tea House” by Rodrigo Culagovski

“Their War” by Vanesa L. Perillo

“The Loving Home” by Olga Fiks

“Siri, My Love; Zuckerbook, My Home” by Mose Njo

“Services” by Marlon Ortiz

“How the Stars Were Connected” by Zhou Wen

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

In addition to half a dozen stories from around the world, this issue offers an article about artwork created by artificial intelligences, based on prompts from human users. Appropriately, the cover features an example of this controversial new process.

“Liz’s Tea House” by Chilean writer Rodrigo Culagovski takes place over several years on a gigantic space station full of bizarre aliens. The narrator starts off as a new arrival, her initial disorientation eased by the Earth-like facility mentioned in the title. She returns to it from time to time after having exotic adventures in deep space.

This is a very lightweight story, with the feeling of fiction intended for younger readers. The pleasant, familiar atmosphere of the tea house creates a warm mood, in contrast to the weirdness of the station and its inhabitants. Even in a semi-comic tale, allusions to modern popular culture (such as I Love Lucy reruns) tend to take the reader out of the story.

“Their War” by Argentinian writer Vanesa L. Perillo is a very brief account of two astronauts aboard the International Space Station who have reasons to hate each other. When war breaks out between their nations, the conflict on Earth has an effect on their personal battle. The premise is provocative, and the author deals with important themes of rivalry and cooperation, but one wishes the story were longer and more fully developed.

“The Loving Home” by Israeli writer Olga Fiks, translated from Russian by editor Alex Shvartsman, features an elderly narrator living alone, but cared for by several artificial intelligences. Those within the house have the personalities of relatives, lovers, and acquaintances, some living and some dead. One is attached to the narrator’s head, serving as an ever-present companion and guardian, and even helping with creative work. When a walk outside turns into a dangerous situation, the limits of AI caretakers become clear.

The premise of the sentient house caring for its inhabitant may remind readers of Ray Bradbury’s famous and oft-adapted story “There Will Come Soft Rains,” but otherwise the works are completely different. The narrator’s personal AI is the most vividly realized character, overshadowing the humans in the story. The ending is heartwarming, but may make the reader wonder why the narrator lives alone in the first place.

The narrator of “Siri, My Love; Zuckerbook, My Home” by Malagasy writer Mose Njo, translated from French by Allison M. Charette, is a refugee from a war-torn nation, escaping on a boat with others, some of whom are already dead. The narrator experiences the world through the rose-colored lenses of virtual reality, so that the horrible situation seems less real than this artificial utopia.

The author powerfully conveys the addictive power of modern electronic media, creating a character more concerned with missing an episode of a favorite series than basic survival. This grim, bitter satire offers an important and provocative lesson, forcing readers to consider their own relationships with distractions from the real world.

In “Services” by Brazilian writer Marlon Ortiz, technology allows the consciousness of a newly deceased person to be stored in a computer, but only for about two hours. Someone who purchases this expensive service in advance is thus able to make last-minute decisions at the time of death, and even enjoy a final meal by being connected to the senses of a living person. The narrator works for the company that provides this posthumous service, and relates an experience with a client.

The author depicts the technology in a realistic, convincing way. The lack of melodrama in the plot adds to the story’s believability. The calm manner in which the client faces her death and impending loss of consciousness also provides verisimilitude. The premise forces one to contemplate one’s own mortality through the use of a deceptively quiet narrative style.

In “How the Stars Were Connected” by Zhou Wen, translated from Chinese by Judith Huang, so-called stargates allow a large number of human colonists to settle other worlds. The company in charge of the program uses tests that reveal individual neurological patterns to choose colonists. Those whose neural connections are too loose are highly creative, but unstable and lacking in foresight. Those with too rigid connections, on the other hand, are unimaginative. Only those who fall between these extremes are selected.

The plot deals with a woman working for the company who secretly exchanges the record of her own neurological pattern with that of a friend. The friend wants to travel to another world, but falls into the unstable category. The woman fits into the medium category, but wants to stay on Earth. When the company’s records become public knowledge, those who have overly loose connections are discriminated against, unable to obtain basic services. A further complication occurs when the colonized planets break off communication with the home world, or send incomprehensible messages in new languages.

I have provided a lengthy and oversimplified synopsis in order to indicate that this is a complex story with multiple speculative premises, some of which I have not mentioned at all. The various concepts are intriguing, even if not all of them are plausible. The almost instantaneous prejudice against those with loose neural connections, who are kicked out of apartments and are not even able to request a shared ride, for example, strains credibility. The climax adds a touch of mysticism to an otherwise scientifically based tale, which may seem out of place to many readers. The plot requires a fair amount of exposition, and the story even comes with its own bibliography of scientific articles.

Victoria Silverwolf found out that the preferred adjective for persons and things from Madagascar is Malagasy.