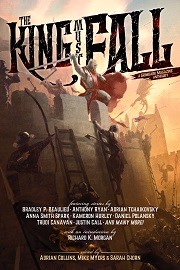

Edited by

Adrian Collins

(Grimdark Magazine, October 2022, 716 pp.)

“What You Wish For” by Devin Madson

“The Dark Son” by Luke Scull

“Glory to the King!” by Anna Smith Spark

“The Book Burner’s Fall” by Anthony Ryan

“Mother Death” by Michael R. Fletcher

“The Black Horse” by Jeremy Szal

“Thrall” by Lee Murray

“King for a Day” by Daniel Polansky

“The King-Killing Queen” by Shawn Speakman

“The Face of the King” by Adrian Tchaikovsky

“Hand of the Artist” by Trudi Canavan

“The Conspiracy Against the Twenty-third Canton” by Alex Marshall

“The Blade-Queen and the Stoneheart” by Anna Stephens

“The Day the Gods Went Silent” by Justin Call

“A Piece of Moveable Type” by Peter Orullian

“The Wizard in the Tower” by Kameron Hurley (reprint, not reviewed)

“The Vârcolac” by Matthew Ward

“On Wings of Song” by Deborah A. Wolf

“The Last Days of Old Sharakhai” by Bradley P. Beaulieu

Reviewed by Seraph

18 original stories and 1 reprint make up a series of stories fit for royalty… or at least to herald their downfall. Some are cautionary tales, while some lean towards the wishful. All serve as a reminder that not everyone who sits on a throne deserves to, and not all those who deserve to sit on thrones do. And, perhaps for some? They’ll wish they never had. Most are set within medieval/ fantasy settings and timelines, but I’ll note when they diverge from that.

“What You Wish For” by Devin Madson

The Kingdom of Vircena was once a mighty empire, prosperous and vast. That was before… before the barrier, before the long decline. Some remember what it was like before the city became a prison, and the fires began to burn into the night as agitators fanned the flames of rebellion. The monsters outside are just a myth to control us they say, the mounting disappearances just the corrupt king vanishing those who would dissent. The king himself doesn’t really do much to inspire, wasting away like a metaphor of the city itself, but little is as it seems and it does not take long for fate to befall his killers. There is a strong horror element, especially towards the end that really elevates this story. The (implicit) warning of the title is paid off beautifully and the foolish earn the reward all fools receive in the end… though not as quickly as they’d have preferred.

“The Dark Son” by Luke Scull

Prince Salidar Karakian is a man scorned and exiled. Once the crown prince of Shar, he was exiled for loving the wrong person, and betrayed even by his lover. Years of wandering and killing now see him return at the head of a fearsome army of merciless warriors. The corruption and decadence of his former home is matched only by the savagery of the invaders. An immortal child Prophet and a cowardly king round out this tale of vengeance, hatred, and murder that doesn’t end exactly as you’d expect it to. Perhaps beneath all the sin and corruption, one last moment of nobility can be found in even the darkest son.

“Glory to the King!” by Anna Smith Spark

King Marith is going to conquer the world. He has everything: power, magic, a massive army fanatically loyal, even a dragon. The crown weighs heavily upon him, though, and the collective voices of the outside world cannot drown out the vicious and demeaning voice inside. This story doesn’t stray from the theme, (it is very much about a king and how he rules), but this is as much a tale about mental health and imposter syndrome as it is a fantasy. I find it leaning more towards the psychological perhaps than the horror or fantasy, though elements of all three are certainly present. The last few lines are a broad and open condemnation of the duplicity and shame of humanity, and really bring full circle why the King struggles to find even the smallest reason why he should continue to live.

“The Book Burner’s Fall” by Anthony Ryan

Kestra Saero is a Sister of the Seventh Order. There were a few different lands named, but I never was able to pin down which was the overall setting. She’s an assassin with a quite literal beast within. As much addicted to killing as she is a vengeful vigilante meting out a bloody brand of justice, she exists in a world somewhere between the pages of a comic book and a land of high fantasy. Hate is the key to her fatal gifts, and her beast coils to strike in the presence of those it preternaturally determines to be worthy of such hate. There isn’t a lot of black and white here, which is good: it wouldn’t work with this style of fiction. Not all the villains are evil, and few of the “good guys” really are. There are shades of grey to everyone, and the consequences of actions are quick to find the actors, main character or otherwise.

“Mother Death” by Michael R. Fletcher

What makes a person? Is it the body, memories, a soul? Add in fantasy elements like being able to store memories and souls inside of stones and the water muddies further. To Mother, life is pain and tragedy as she is forced to watch a rival tribe kill her children and steal their souls, their very potential of the life they will never have. They kill her and rob her of her very self, but this only begins her journey. She rises again and carves a bloody path through warriors and sorcerers alike, each time gaining not only their memories and skill, but those they carry as trophies as well. It’s an interesting twist, as she becomes death incarnate and becomes mother to all that she slays.

“The Black Horse” by Jeremy Szal

If I could put this story into a single concept, it’s a brutal anthropomorphic bloodbath showcasing the worst of humanity. Living in Kharkov as a member of the Guild, Yharv is a Bolokov, a Kin race of horse-people. He carries a dark secret with him, a betrayal that led to the deaths of many of his people. When he finds himself in a position to choose between the life of one nearly extinct Kin and the fall of the entire city, he doesn’t hesitate. I don’t use the word brutal lightly: the story is full of torture, mutilation, slavery, murder, and if it doesn’t directly depict all the other worst sins of humanity it certainly threatens them. There’s a very powerful message in here, but it isn’t a new or inventive take on it, and it mostly gets lost in the descriptive savagery.

“Thrall” by Lee Murray

Though the fantasy elements are still very present here, this story is set in the real world, near New Zealand. It focuses around the mythical selkies, and is a cautionary tale of exploitation, greed and the mistreatment of captives. As above so below, and there aren’t any happy endings in such a tale. The Endeavor is a hunting ship aiming to be full to the deck of the skins of clubbed seals, until one day one of the seals… isn’t. The woman sheds her seal-skin after one of her pups is clubbed, and is captured by the greedy captain after the sailors spare her. At every point the greed and desperation of the captain and crew lead them to their inevitable doom, and it’s with a certain degree of satisfaction that the captain indeed goes down with the ship.

“King for a Day” by Daniel Polansky

What do you get when you take one golden Torc that magically binds to the wearer to make them a living god, a dead god-king, and a city full of misery and greed? A whole lot of death and betrayal, and no ruler. The litany of names that the Torc passes through bear no importance, nor mention. The Pyramid atop his Mountain Cuauhtemotzín serves as much of the setting, and there is a definitively Central American theme to the whole story, but as the Torc passes from person to person, the only thing that really matters or even stands out in the story is just how vile and greedy people can be. Perhaps the only mercy or redeeming quality here is that the author doesn’t feel the need to explicitly detail each and every death.

“The King-Killing Queen” by Shawn Speakman

History is written by the victor, and victory does not guarantee virtue. More often than not, such histories gloss over or omit entirely the sins of the victor, no matter how glorious their achievements may truly have been. The character High King Alafair Goode clearly draws inspiration from both Arthur of legend and David of the Bible, but isn’t just a medley of borrowed history and myths. When he chooses his brilliant but hitherto unknown daughter to be High Queen after him, the many unworthy heirs refuse to accept her, and betrayal waits around every corner. This could have easily been just another tired rehash of Arthurian legend, or another girl-power fluff piece, but it isn’t. Sylvie doesn’t come to rule the kingdom without steel in her soul, and she has been preparing for this her entire life, albeit unknowingly. Hard truths and harder choices are laid before her, but she is the worthy heir. Not because of birth, or gender, or some magical ability… through strength of resolve and character. This is an increasingly rare stroke of the pen, and I recommend it strongly.

“The Face of the King” by Adrian Tchaikovsky

The King of Narad-Var must never show his face. Hidden behind an ornate mask, such theatre maintains the illusion of divinity and separates him from those he rules. It also makes it ridiculously easy to assassinate and replace him. A pact made with a dark god hovering above a forgotten altar leads to a messy vengeance and a surprise twist. The pacing is solid, the twist is intriguing (if a bit macabre, but that fits well here), and the payoff at the end is worth the read.

“Hand of the Artist” by Trudi Canavan

The King of the Mountain is sick, and that word has multiple applicable meanings. The main voice is never given a name, but she is as elegant and artistic as this story. In one of the more artful stories in the anthology, the young lady is hidden away by her parents until an agent of the king’s tax comes searching for hidden treasure. Yet when she finally makes it to the Palace, it isn’t at all what she dreamed it would be. Yet among her many talents, her painting quite literally has the power to cure the madness and corruption that haunts the King. This piece isn’t devoid of ugliness: it’s on full display as much as any of the rest of the stories in this anthology. But the cure here isn’t an execution or a raping, pillaging army…. The cure is literal healing; you could even call it the healing arts if you’d like to be cheeky.

“The Conspiracy Against the Twenty-third Canton” by Alex Marshall

Vhumi is soon to be the Tapei of the Twenty-Third Canton of Ugrakar, once she eats the flesh of her dying father. Yeah, we start with ritualistic cannibalism and kind of go from there. Vhumi doesn’t want the throne, but dreads the younger brother having it even more. What follows is a fever-dream fantasy about changing fate and defying destiny, with a flair of the mystical. Body-swapping, body-eating, and stolen lives round out what otherwise could have been a fairly intriguing tale. It isn’t badly paced, and it is plenty descriptive, but something about cannibalism just… turns my stomach.

“The Blade-Queen and the Stoneheart” by Anna Stephens

Anyone who is familiar with Kerrigan from Star-Craft should have a rather easy time visualizing this story. Take the Queen of Blades and make it a fantasy setting instead of an SF setting and you’re already getting close. That’s not to say this is just a copy: there’s a fair amount of added detail here which is appropriately… squirmy, but there’s not a lot that feels truly original here. Alaya is a Blade-Queen, and rules over the city of Sisterne in the land of Sistral. The populace is essentially in a constant state of revolt, stirred up by a succession of petty, jealous husbands, until the Queen is finally killed in a scene highly reminiscent of Tolkien’s Eowyn slaying the Witch-King. Undoubtedly there is a crowd that this will appeal to, but I can’t get there.

“The Day the Gods Went Silent” by Justin Call

This is a very intricate story with a lot of moving parts. There are far too many characters to name in such a short space, each of them playing a crucial part in the outcome. For the most part, it takes place in Speur Dun, the capital city. The primary thread is the theft of three powerful objects during the coronation of a new King, the first King and the end of an age. Plots swirl around the young ascendant, who unexpectedly becomes a Child-God during the ceremony, but this is not enough to save him from the machinations of those around him. It feels like this could be part of a much more expansive world setting, and is full of references and plot seeds that could feed many more books. It was thoroughly enjoyable, and my only real complaint is that it maybe felt a little bit too full for its length. There is so much going on that would be amazing to read more about, but it deserves a lot more time and space in which to be fleshed out.

“A Piece of Moveable Type” by Peter Orullian

This one is set in Germany during the reign of Frederick, soon to be Holy Roman Emperor, and could fall easily within the category of historical fiction. Given that the subject matter is Gutenberg and the printing press, there are definitely religious/supernatural tones as well, but mostly it focuses on poor Johannes and his many trials. The pacing is a little off in the beginning, but the author quickly finds his stride and throws in several interesting little twists and turns. The one thing that stood out most was how deftly the author sets up and then delivers the twists and reveals, in a way that is constantly subverting the expectations that seem to be implied throughout. That alone earns it a recommendation in my mind.

“The Vârcolac” by Matthew Ward

While this story should absolutely be taken on its own merit, it struck me that it is also a delightful reversal of the “Little Red Riding Hood” fairy tale. I don’t know if that was intended or just happy chance, but this is a wild ride. Govadra Tiranas and his Immortals are seeking to cast down a real monster of a ruler, one who names himself after ancient bloodthirsty creatures. The Tressians who defend this king are no match for his Kentae, especially for his adopted daughter Jennica. As with many tales of vengeance, he digs his own grave alongside that of his foe, and it is only in the last moments that he truly understands who his true enemy is. Far too late, for the real ancient beast was not the king, but one by his side, now at his throat. This was a thoroughly enjoyable story, and an easy recommendation.

“On Wings of Song” by Deborah A. Wolf

Lille is the child of a god, Allyr. With wine-red scales and silvery eyes, she and her sisters are called sirens. While most of the sirens have yet to find their voices, Lille is a masterful bard, with a hauntingly beautiful voice and the skill in music to match. She meets another bard, a handsome young man named Zymander, who grows jealous of her gifts and tries to steal them for himself. The revenge tale element is simple enough and fairly standard, but the artistry in the story comes from Lille’s encounters and interactions with her sisters. It is Lille who teaches them to sing, who gives them the gifts to defend themselves against those who would prey upon them, and is in turn welcomed as a true daughter of her deific father. It is in the arms of her sisters that she discovers love, and of trust, and it is her sisters who bring her the vengeance she claims in the end. There is an elegance to this story, and a beauty.

“The Last Days of Old Sharakhai” by Bradley P. Beaulieu

Ihsan, the last King of the land of Sharahhai and he of the Honeyed-Tongue, is dying. Change has come to his lands and his people, and a new Covenant is being forged that will ensure peace and representation to the people. As one might expect, those who might have been in line for the throne once he passes are less than pleased, as are the old nobility who might see reprisal in a time when they no longer hold such sway. Strangely, old enemies become his closest allies and those closest to him prove to be traitors, but such is the danger of a crown. He has ruled for centuries, and with all that is left of his power he navigates the treachery towards a future of peace for his people. The pacing here is really solid, and the author takes the right amount of time to set up and then pay off the various story threads. There are plenty of mystical elements as well as skilled warriors, and the final story of the anthology does not disappoint.

The King Must Fall

The King Must Fall