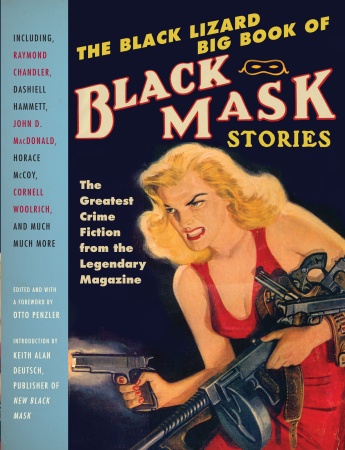

The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories

The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories

Edited by Otto Penzler

(Vintage, September 21, 2010, 1,100+ pp., $25)

Reviewed by Dave Truesdale

Otto Penzler, editor of more than 70 collections ranging from the detective to the vampire story, has once again put together what is sure to become a classic with The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories.

Culled from the pages of the legendary detective pulp magazine Black Mask, this weighty tome (a good five pounds) showcases 51 stories, including 2 complete novels, and runs to a staggering 1,100+ pages.

Penzler begins the book with a short foreword, relating his efforts in compiling the stories, many of which have never before been reprinted since their first appearance in the magazine and which were extremely difficult to track down.

He begins his foreword with the following:

“This is not the first anthology to be devoted entirely to the mystery fiction contained in the pages of Black Mask magazine, but I am confident that I will be accused of neither hyperbole nor immodesty when I state unequivocally that it is the biggest and most comprehensive. Indeed, apart from The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps, published by Vintage in 2007 and to which this volume is a sequel of sorts, The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories is the biggest and most comprehensive collection of pulp crime fiction ever published.”

Keith Alan Deutsch, publisher and editor of the newly revived Black Mask, follows Penzler’s foreword, and provides an extensive historical introduction, detailing the events surrounding the founding of the magazine–including fascinating details of the pulp magazine industry in general, and the various people and publishers involved–its initial focus, its most famous (and not so famous) editors, and spices the mix with his own insider commentary on some of the stories included in this landmark volume.

Deutsch opens his introduction, and sets the stage for what is to follow with these words:

“This panoramic collection of stories and novels from Black Mask magazine (1920-1951) is the most comprehensive presentation of the hard-boiled detective tradition of writing ever published from this great magazine. I believe this is a significant publishing event because Black Mask introduced the hard-boiled detective, and a new style of writing, to American literature.

“In many ways, Black Mask took the nineteenth-century American Western tale of outlaws and vigilante justice from its home on the range in dime novels, and transplanted that mythic tale to the crooked streets of America’s emerging twentieth-century cities. It introduced a new landscape for both American adventures of justice and also a new kind of narration told with the vernacular language of the streets, and featuring new urban villains, and urban (if not always urbane) heroes for the mystery story.

“The first hard-boiled detectives were men of the city, all: Carroll John Daly’s Three Gun Terry and Race Williams appeared primarily on the wild streets of New York, talking wise and walking that eternal tough-guy-detective line between the law and the outlaw. The first great detective narrator of the new hard-boiled fiction, Dashiell Hammett’s professional lawman, the Continental Op (the first Op tale is included in this collection) operated famously in San Francisco, as did Hammett’s iconic detective, Sam Spade.

“Surprisingly, soon after the publication of The Maltese Falcon, Gertrude Stein declared Hammett, not Hemingway, the originator of the modern American, declarative, narrative sentence.

“Arguably the greatest stylist of the hard-boiled genre, Raymond Chandler, observed such a fully realized and corrupting Los Angeles landscape in his poetic vision of the Black Mask detective tale that his writing has become the literary standard for all twentieth-century narratives of that city, or of any other American city.”

These are but the first five paragraphs of what amounts to nine pages of small-type introduction to Black Mask, its authors, their stories, and their historical place within the magazine and the crime/detective fiction genre as a whole. By the time the reader has immersed himself in this beautifully drawn, fact-filled world of the pulp detective story, one can readily understand the eagerness to read the stories themselves. Keith Alan Deutsch has performed his task admirably, for the reader is primed and ready to dive into the world of the hard-boiled detective milieu and experience first hand why it has become so popular–in books, on radio, on the silver screen, and on television.

Some of the most well-known names are of course represented, authors such as Erle Stanley Gardner (creator of Perry Mason, among others), Dashiell Hammett (creator of Sam Spade, among others), Raymond Chandler (creator of Philip Marlowe), as well as a host of lesser known names only the detective fiction aficionado would recognize, but whose work is, in its own way, as important, or which shines as brightly as those of the more well-known.

Take Carroll John Daly (1889-1958), for instance. Daly’s importance to the hard-boiled detective genre cannot be underestimated. With one story he single-handedly invented the genre. As Keith Deutsch explains in the introductory notes to the Daly story included here, “While there had been private detectives in literature before Daly, including Sherlock Holmes, and there had been dark, violent stories by such writers as Jack London and Joseph Conrad, it was not until Black Mask published “Three-Gun Terry,” about the tough, wisecracking private investigator Terry Mack, in the issue of May 15, 1923, that the style and form coalesced.”

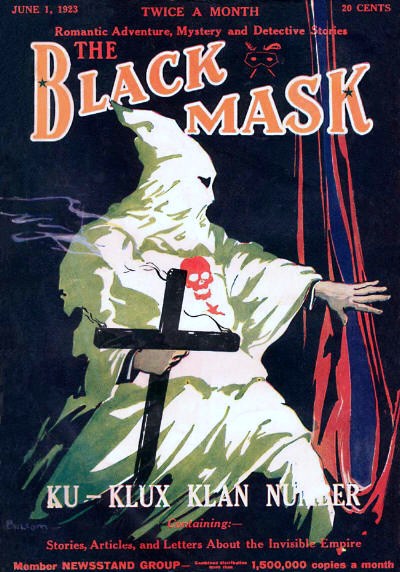

Daly’s story here is his second published story, appearing in the issue following “Three-Gun Terry,” and features his second most famous character Race Williams. “Knights of the Open Palm” appeared in the June 1, 1923 issue, and concerns Williams’ infiltration of the Klu Klux Klan in the solving of a mystery (the Klan was involved in more than just the race issue; this story shows their other activities included corruption and the liquor industry). The “open palm” of the title refers to but one of several Klan signals used to identify themselves to other members.

Daly’s story here is his second published story, appearing in the issue following “Three-Gun Terry,” and features his second most famous character Race Williams. “Knights of the Open Palm” appeared in the June 1, 1923 issue, and concerns Williams’ infiltration of the Klu Klux Klan in the solving of a mystery (the Klan was involved in more than just the race issue; this story shows their other activities included corruption and the liquor industry). The “open palm” of the title refers to but one of several Klan signals used to identify themselves to other members.

“Knights of the Open Palm” is not the only story dealing with the Klan. Appearing in the same June 1923 issue as “Knights” (this has the appearance of a themed issue), Richard Connell’s “The Color of Honor” deals more directly with the theme of racism and the Klan. While not a hard-boiled detective tale, the hard-boiled approach is certainly present, as a young man inherits his family’s generation’s-old southern mansion and land. The “honor” of the title takes on a deeper meaning than that of the family’s honor, when the young man discovers a Klan robe in an attic trunk (his great uncle served with General Lee in the Civil War). This quite short story (nine pages) is excellently crafted, and turns on the young man’s realization that there is greater honor than family tradition when he sacrifices much in aid of a black man (a “nigger”) who refuses to move when the “responsible white men of the community” make him an offer he can’t refuse. A brave, tension-filled and memorable story.

While Connell’s name may not be familiar to many for his fiction, he was rather prolific, dividing his time between his stories for the pulps and the slicks and writing films for Hollywood. A prime example is Connell’s most famous story “The Most Dangerous Game.” Widely anthologized, it has been filmed numerous times, first in 1932 and starring Joel McCrea and Fay Wray (see the Old Time Radio episode here for more on McCrea and Wray), again in 1945 as A Game of Death, and a third time in 1956 as Run for the Sun (starring Richard Widmark and Jane Greer).

Along with stories involving the Klan, and racism, there is the issue of sexism in the hard-boiled detective and mystery magazines, Black Mask being no exception. Introducing the only story written by a woman and featuring a female protagonist, Keith Deutsch says of Katherine Brocklebank’s “Bracelets”: “Katherine Brocklebank was unique in the history of Black Mask magazine, and a rara avis in the detective pulp fiction world in general. In the first place, she was a woman and, unless cloaked behind initials or a male pseudonym, the only one identified in the thirty-two-year history of Black Mask, even when it was under the control of a female editor, Fanny Ellsworth, from 1936 to 1940. Second, she created a female series character, Tex of the Border Service, who appeared in four stories late in the 1920s. Readers of Black Mask, as was true of all the detective pulps, demonstrated in their letters to the editor that they didn’t particularly care for either female protagonists or authors.”*

*[Please forgive the following digression: While this bias against female protagonists and authors existed–and was more pronounced in the detective and mystery pulp magazines than perhaps elsewhere–it showed itself in many of the pulps of the time, including the science-fiction pulps. Much has been made over the past several decades of science-fiction’s sexism in its early years, as if those writing about such matters believed science-fiction was unique in this regard. It was not. Today’s readers must remember that the vast majority of the pulp magazines of all genres were written for a young male audience, and publishers simply published what they learned, through trial and error, would sell the most copies of their magazines. It was a business decision, and a product of the culture and the time in which the magazines were published. That said, and in context, the science-fiction pulp magazines were actually more open to female authors and protagonists than most pulp magazines of the time–and certainly more open than the detective and mystery pulps. Maybe not by much when taken as a percentage of stories published, but nevertheless more accepting than most of the genre pulps. As Deutsch explains, Black Mask was no exception among the many detective and mystery pulps of the time in their almost total avoidance of female authors and protagonists–as witness the Brocklebank story being the only exception he could find in Black Mask’s history. By comparison, if we take a look at an even narrower time period of the SF pulps we can confirm their more relative openness to the female author and protagonists. Isaac Asimov Presents the Great SF Stories (ed. Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg) ran for 25 volumes, chronicling what they perceived as the best SF from the years 1939 (when John W. Campbell, Jr, began his reign as editor of Astounding Science Fiction–now Analog–and ushered in the Golden Age of SF) to 1963 (the year before the Science Fiction Writers of America–SFWA–was formed in 1965 and their first Nebula Awards for stories from 1964 were given proper recognition).

Black Mask ran from 1920 to 1951 and published but one female author. According to the stories selected by Asimov and Greenberg (what they considered the “great” stories, so there were undoubtedly more stories not in these collections) from 1939 to 1951, the SF pulps produced stories by C. L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, Judith Merril, Katherine MacLean, Wilmar H. Shiras, and Julian May, and all under their own names (though the Moore and Brackett could have been taken as male names, to be fair). And three of the six more than once. Not counting the dozen pseudonymously penned stories by the husband and wife team of Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore from 1939-1951, Asimov and Greenberg included another dozen by the names noted above. While one can find the rare grumble against a female writer in the letter section of a few of the SF pulps of the time, by and large the vast readership didn’t seem to care who wrote their favorite type of story. This observation is reinforced when one considers the comments and writings by various male and female authors of the era who recount that female authors were welcomed with open arms into the SF field–both in fan organizations across the country and at the conventions. Therefore, if one goes solely by the numbers in SF magazines and disregards other relevant factors, the science-fiction pulps might therefore appear to be the prime example of a sexist genre some make it out to have been. But if one places the “sexism” in context with other pulp magazine genres–not exclusive to, but especially the detective and mystery pulps–the SF pulps can be seen in broader context and in a somewhat more forgiving light. Indeed, aside from the romance pulps and a few others written specifically for the young female audience, the SF pulps were more open to female writers than any other pulp genre.]

So what about the only known story by a female author in Black Mask’s history? “Bracelets” has a female border security guard known as “Tex of the Border Service” involved with kidnapping, murder, and a bracelet that holds the secret to the intrigue, and which finds Tex crossing into “Tia juana” to do some undercover work in a sleazy south of the border bar tricked out as a “percentage girl.” After taking some hard knocks, she proves herself a smart, tough, and worthy adversary to those who underestimate her. A fast-paced, down-and-dirty tale fully worthy of the “hard-boiled” descriptor.

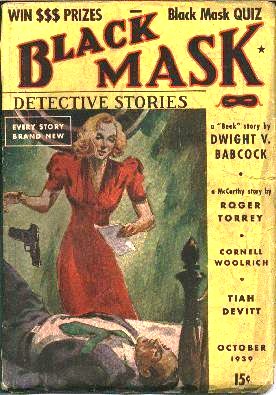

Though Katherine Brocklebank might have been the sole woman author to appear in Black Mask’s thirty-two years, editor Penzler has chosen to include a two-page charge of dynamite with William Cole’s “Waiting for Rusty,” which sports a tough gun moll holed up in a roadside diner waiting for her boyfriend Rusty, who is but one short step ahead of the coppers following a spectacular robbery. As it is soon made clear, he has abandoned her, something her love for him will not admit. When the cops arrive in hot pursuit at the diner and “Dotty” steps out to greet them, guns blazing…well, the ending is unexpected. According to editorial notes written shortly after the story saw print, it “elicited more reader response than almost any story ever to appear in the magazine.” This little gem was published in the October 1939 issue.

Though Katherine Brocklebank might have been the sole woman author to appear in Black Mask’s thirty-two years, editor Penzler has chosen to include a two-page charge of dynamite with William Cole’s “Waiting for Rusty,” which sports a tough gun moll holed up in a roadside diner waiting for her boyfriend Rusty, who is but one short step ahead of the coppers following a spectacular robbery. As it is soon made clear, he has abandoned her, something her love for him will not admit. When the cops arrive in hot pursuit at the diner and “Dotty” steps out to greet them, guns blazing…well, the ending is unexpected. According to editorial notes written shortly after the story saw print, it “elicited more reader response than almost any story ever to appear in the magazine.” This little gem was published in the October 1939 issue.

The bulk of the collection is, as you might expect, comprised of stories featuring detectives or private investigators, though also present are stories with likeable small-time crooks who outwit their fellow criminals, while some feature ordinary guys drawn into strange mysteries often rife with double-dealing and murder.

In the likeable small-time crook category we have Ray Cummings’ “T. McGuirk Steals a Diamond” from the December 1922 issue. Cummings is better known in SF circles as the author of the early 1919 classic (and his first story) “The Girl in the Golden Atom.” With this single story he would later be known as “the founding father of pulp science fiction.” Cummings would write a total of 14 McGuirk stories for Black Mask, of which this is the first. I must admit Cummings kept me guessing as I couldn’t figure out how McGuirk stole an expensive diamond right under his fellow thieves’ noses. A delightful puzzler.

A worthy example of a mystery featuring an ordinary guy drawn into mayhem and murder is “The Shrieking Skeleton” as by one Charles M. Green. Green was a pseudonym (one of many) used by none other than Erle Stanley Gardner early in his career, long before he would enjoy the fame and fortune afforded him by his Perry Mason novels, the first of which saw print in 1933. In “The Shrieking Skeleton” a young man has received a letter from his older friend, one Dr. Alfred Potter, informing him that he has purchased the corpse of his long-time enemy Elbert Crothers, and reduced it to its skeleton, which the doctor has hung in a closet for gloating inspection when the mood strikes him. The young man visits his old friend with more than one question begging to be answered, but before long he is knee deep in unexplained occurrences in Dr. Potter’s old mansion, including the spine-tingling cries emanating from “The Shrieking Skeleton.” Published in the December 1921 issue, this bizarre whodunit provides thrills and chills as well as an element of international espionage. A highly entertaining novelette.

Under his own name, Erle Stanley Gardner also opens the collection with what might be considered a prime example of the stereotypical “hard-boiled” mystery story, with his “Come and Get It” from the April 1927 issue. One of Gardner’s most famous early pulp series characters, Ed Jenkins (the “Phantom Crook“), is warned to beware of a girl with a mole, that she will lead him into deadly peril. This friend and fellow thief, warning given, is then quickly murdered, almost literally on Jenkins’ doorstep. The chase is on, and the knotted mystery is afoot in this deadly page-turner. A fine opener to the collection and well chosen.

Under his own name, Erle Stanley Gardner also opens the collection with what might be considered a prime example of the stereotypical “hard-boiled” mystery story, with his “Come and Get It” from the April 1927 issue. One of Gardner’s most famous early pulp series characters, Ed Jenkins (the “Phantom Crook“), is warned to beware of a girl with a mole, that she will lead him into deadly peril. This friend and fellow thief, warning given, is then quickly murdered, almost literally on Jenkins’ doorstep. The chase is on, and the knotted mystery is afoot in this deadly page-turner. A fine opener to the collection and well chosen.

Following “Come and Get It” we have one of a handful of stories peppering the collection by authors well known to the science-fiction/fantasy reader. Frederic Brown’s “Cry Silence” (November 1948) is a prime example of his brilliance at the short-short length. At a mere three pages Brown’s tale of deception, an abused wife who cheats on her cruel husband, and ghastly murder, turns on the philosophical question of whether or not there is a sound if a tree falls in the forest but there is no one there to hear it. Ingenious.

Lester Dent, who created Doc Savage in response to the success of The Shadow magazine and wrote Doc’s adventures under the house name of Kenneth Robeson, wrote two stories for Black Mask featuring his second most famous character, Oscar Sail. Both the first one, “Sail,” (October 1936) and the second, “Angelfish,” have been widely anthologized as “outstanding examples of the hard-boiled pulp detective.” Alas, Dent was asked to rewrite “Sail” so many times that he “did not care for the final product.” Will Murray, agent for Dent’s estate, found a much earlier version of “Sail” and certainly one which Dent would have preferred. It is published here for the first time anywhere as “Luck,” and a lively bit of mayhem it is, awash in Greeks, gambling, and bloody murder.

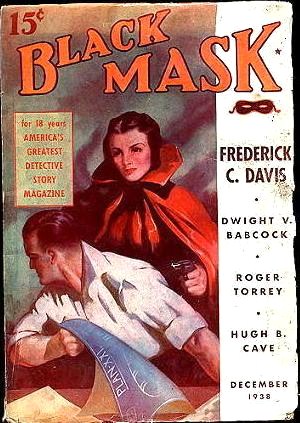

Other excellent stories by SF/F or closely associated authors include Norvell Page’s “Those Cantrini” (February 1933), Hugh B. Cave’s “Smoke in Your Eyes” (December 1938), Cornell Woolrich’s “Borrowed Crime” (July 1939), and C. M. Kornbluth’s deceptively titled “Beer-Bottle Polka” (September 1946). The original pre-story blurb entices with: “A private eye is supposed to be in the know. That was where the blow came to Tim Skeat’s pride–he was supposed to be, but that was all. A carved-up corpse, a punk with a gun, and a mob at his heels for a secret he didn’t have–tough-guy Skeat took and gave a lot of punishment before the ugly picture began to make sense. And he was almost sorry when it did.” No hyperbole here, as the deadly conclusion rewards with a most satisfying payoff. Which, of course, is no surprise to those familiar with Kornbluth’s work.

Other excellent stories by SF/F or closely associated authors include Norvell Page’s “Those Cantrini” (February 1933), Hugh B. Cave’s “Smoke in Your Eyes” (December 1938), Cornell Woolrich’s “Borrowed Crime” (July 1939), and C. M. Kornbluth’s deceptively titled “Beer-Bottle Polka” (September 1946). The original pre-story blurb entices with: “A private eye is supposed to be in the know. That was where the blow came to Tim Skeat’s pride–he was supposed to be, but that was all. A carved-up corpse, a punk with a gun, and a mob at his heels for a secret he didn’t have–tough-guy Skeat took and gave a lot of punishment before the ugly picture began to make sense. And he was almost sorry when it did.” No hyperbole here, as the deadly conclusion rewards with a most satisfying payoff. Which, of course, is no surprise to those familiar with Kornbluth’s work.

Needless to say, I have perforce mentioned but a few of the more than fifty stories here. I could go on forever and would still fall short of conveying the breadth and depth and ingenuity of these hard-boiled crime tales. All of the usual themes are represented, virtually all including or ending in at least one murder (ofttimes grisly): fraud of various types (insurance or inheritance), jealousy, robbery, political corruption, greed, racism, organized crime, illegal immigration, and arson. The locales vary rather surprisingly, from southern Florida to the southwest border, with a few stops in between; though many, as you might imagine, are set in New York, Los Angeles, or San Francisco.

The crowning jewel of this otherwise already sparkling collection must without doubt be Dashiell Hammett’s iconic novel The Maltese Falcon. Hammett (1894-1961) saw his novel serialized first in Black Mask. As the introductory note explains:

The crowning jewel of this otherwise already sparkling collection must without doubt be Dashiell Hammett’s iconic novel The Maltese Falcon. Hammett (1894-1961) saw his novel serialized first in Black Mask. As the introductory note explains:

“Like most of Hammett’s important work, The Maltese Falcon was originally published in Black Mask. It was a five-part serial running from September 1929 to January 1930; Alfred A. Knopf published it in book form on February 14, 1930.

“The book was dramatically revised after serialization, with more than two thousand textual differences between the two versions. Some of these changes were made by copy editors at Knopf but the majority appear to have been made by Hammett himself. This is the first time that the original magazine version has been published since its initial appearance eighty years ago.”

As editor Otto Penzler points out in a Tangent Online interview, many of the changes to the book version were small, on the order of tweaking a word here or there or smoothing out a sentence, both versions gaining or losing a bit here and there, but on the whole neither version being superior to the other.

I had not read the book but have watched the movie at least a dozen times, never losing my enjoyment of this classic noir film. Reading this original magazine version for the first time was like watching the movie all over again, so close was the printed dialogue and descriptions of the characters like the film. Aside from the fact that Hammett’s Sam Spade is tall, well-built, and sports blonde hair, as opposed to Humphrey Bogart as a short, dark-haired Spade (can you visualize anyone else playing Spade in this movie? Impossible.), the casting of the movie is (almost) perfect. Sidney Greenstreet as the fatman Casper Gutman, whose lifelong search for the bird has led to Spade’s involvement, and Peter Lorre as the effeminate Joel Cairo. All three perfectly cast. If you’ve seen and remember the movie, you can hear the voices of Bogart, Greenstreet, and Lorre as you read, seeing the film, scene by scene, as it slides through your mind’s eye. It may sound odd but you can literally read the movie so faithful is its adaptation to film. The only major character miscasting from book to film–and this is not the fault of the book, of course–was Mary Astor as the conniving, lying seductress who attempts to steal Spade’s heart while also in search of the bird. While Astor nails her role admirably, she looks much too old and not nearly as beautiful as the Brigid O’Shaughnessy character as described by Hammett. But that’s just me.

Personal opinion aside comparing the print version to the classic film, it was a rare treat being able to read this original magazine version. It’s a magnificent tale in and of itself, perhaps the best hard-boiled crime novel of all time, and I’m reasonably certain some will argue worth the price of the book itself, for, as the novel’s intro note proclaims, it is “the most famous mystery novel ever written by an American.”

Of several general observations I could impart to the prospective buyer pertaining to the actual stories themselves, one seems to have struck me–for whatever reason–as representative of the overall ruthless, uncompromising world in which these stories were conceived and written, and which they reflect. While one expects the killing and murder to take the usual forms: stabbing, gunshot, bludgeoning, and even poisoning, one can’t help but notice the number of times a victim or villain–both male and female–aren’t merely shot, some multiple times in the chest or abdomen, but right between the eyes.

Hopefully, this is how this historic collection will hit you as well. Right between the eyes.