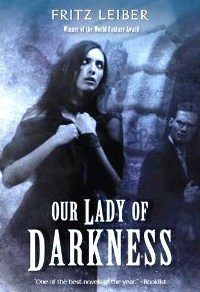

by Fritz Leiber

(Tor/Orb. September 2010)

by

Nader Elhefnawy

In 1977 The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction published Fritz Leiber’s novel “The Pale Brown Thing.” Under its subsequent (and far more evocative) title Our Lady of Darkness the following year, that novel won the World Fantasy Award in its category, and today enjoys the status of a classic. This year Tor Books reissued the book in its own volume, with endorsements on the cover identifying it as a “Masterpiece,” a “pioneering work of modern urban fantasy,” and the “greatest novel” of the storied career of Fritz Leiber (1910-1992). After reading the book itself, some will enthusiastically agree, but others will find themselves completely confused by the accolades.

Our Lady centers on Franz Westen, a widowed and formerly alcoholic pulp writer with a lot of time on his hands in ’70s-era San Francisco (in short, a rather obvious stand-in for Leiber himself) who is intrigued by a figure–a “pale brown thing” he spots in Corona Heights Park from his apartment window. Coincidentally, his eye then falls on a pair of old books he bought years ago–Megapolisomancy: A New Science of Cities by one Thibaut de Castries, and a journal apparently kept by Clark Ashton Smith of Weird Tales fame–and it strikes him that these might have something to do with that mystery. His fancy tickled, he decides to check out Corona Heights for himself, and what starts as a lark soon enough immerses him in a Lovecraftian mystery amid obscure old books and archives, involving the secret history of San Francisco as influenced by Victorian occultism.

Readers anticipating a straight piece of urban fantasy such as the blurb on the back of the book promises may enjoy the book’s well-grounded characters, its allusiveness, or its profusion of ideas, in particular an intriguing central concept in “megalopolisomancy,” a “magic” of super-cities in which urban design has “paramental” effects. They may feel a twinge of nostalgia for the 1970s, and appreciate the story’s touches of what has since come to be called steampunk. However, the book as a whole would seem to them something of a letdown. Not only is the first half of the novel dominated by a slow build-up almost devoid of tension or suspense, but at the end it may seem as if a satisfactory “pay-off” to that build-up never really arrived, especially if they keep the comparison with Lovecraft that Westen himself makes inside the novel in mind. Rather than the grand confrontations with the supernatural at the heart of Lovecraft’s stories, Westen has little brushes that are more ontologically rattling than viscerally horrifying. Instead of witnessing living nightmares that he can only try desperately to suppress, the things he sees come off as unreal, as if they might turn out to be optical illusions and other misapprehensions. Just as Lovecraft tended to be vague about such matters as the contents of the storied Necronomicon, the reader is treated to very little of the contents of Megalopolisomancy. However, where Lovecraft’s hints foster a sense of eons and immensity dwarfing not just the onlooker, but the entire human species, this story felt awfully small in spite of the megacity-level scale of its conjuring techniques, and the evocation of a history as old as civilization. Instead of a figure of power, menace and mystery, the central book’s author De Castries’ seems more like a colorful but ultimately pathetic faker (though his story, the telling of which takes up about an eighth of the book, may seem like a more interesting one than Westen’s rather slight adventure).

In commenting on Our Lady of Darkness in their essential Encyclopedia of Fantasy, John Clute and John Grant correctly note that Leiber smoothly underplays his material. What may seem disappointing or even frustrating to some horror fans is actually quite deliberate. Misleading publicity aside, Our Lady is not a straight-faced update or adaptation of the Cthulhu mythos in the manner of, for instance, Charles Stross’s “A Colder War,” but a subversion of it, in line with the reassessment of the older canon of the kind with which the New Wave of his day was so often identified. More than anything else, this book made me think of the critique of Lovecraft Michael Moorcock presented in his contemporaneous essay “Starship Stormtroopers,” where he put down the creator of Cthulhu as not only a “racist misogynic,” but “a promoter of anti-rationalist ideas about racial ‘instinct'” sharing the “negative romanticism of much Nazi art” and Hitler’s Mein Kampf itself, but an “offensively awful” writer unable “to describe his horrors (leaving us to do the work–the secret of his success–we’re all better writers than he is!).”

Leiber, praised by Moorcock in that very same essay as “the best of the older American sf writers,” for, among other things, “his wit and his humanity, as well as his abiding contempt for authoritarianism,” would seem to live up to that praise with his new take on the Cthulhu mythos, pointedly discarding the older writer’s racial and sexual baggage, cutting the implied horrors down to size and using reason to defeat anti-rationalism, all with a spirit of play much like what he previously brought to sword and sorcery in the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories. It is on this level that Our Lady succeeds–admirably, but problematically, since this approach is best suited for a hardcore readership capable of not only recognizing but appreciating such a spin by one giant of science fiction on the work of another.