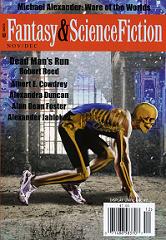

“Dead Man’s Run” by Robert Reed

“Dead Man’s Run” by Robert Reed

“Plinth without Figure” by Alexander Jablokov

“Swamp City Lament” by Alexandra Duncan

“Death Must Die” by Albert E. Cowdrey

“The Exterminator’s Want Ad” by Bruce Sterling

“Crumbs” by Michaela Roessner

“Venues” by Richard Bowes

“Planning Ahead” by Jerry Oltion

“Free Elections” by Alan Dean Foster

“Ware of the Worlds” by Michael Alexander

“The Closet” by John Kessel

“Teen Love Science Club” by Terry Bisson

Reviewed by Mark Lord

Robert Reed’s novella “Dead Man’s Run” is a murder mystery involving a group of elite runners. Wade is a running guru and training shoe salesman who has been murdered, and now his avatar, who has survived his death, wants to know who did him in. In some ways this story would work quite well with the SF elements of the avatar taken out. The setting is near-future Earth with some hints that climate change is a major problem causing weather conditions to falter and internal migration in the US. Yet a lot of the action and the emotional conflict between characters does not rely on this setting or the avatar concept; for instance one could easily replace “avatar” with “memory of”. Despite that, I enjoyed the story because of the way the tension built – every other scene in the novella is part of an organized training run taken by Wade’s former customers, friends and suspected murderers. As the run progresses tensions between the runners increase as does the weariness of their muscles. The run becomes a chase and carries the story and the reader with it. I think that on the level of pure story-telling “Dead Man’s Run” is amongst the front-runners in this issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

“Plinth without Figure” by Alexander Jablokov is a tale of architecture, ghosts and lost love. Frederick is an architect commissioned to redesign part of a city somewhere in the US. He has begun his planning process by collecting data on how people use that part of the city and how they feel about the urban space they engage with and how they might feel if it changed. Frederick gets reports that some of his urban lab rats are experiencing the sensation of seeing a ghost at Carver Square in his part of the city. He discovers that the ghost relates to an incident with a ghost that he shared with Andrea, his ex-girlfriend, and furthermore that she is somehow responsible for the ghostly impression on his urban design. This story does a good job of introducing a paranormal story device into a narrative about lost love, while carrying with it an impression of intellectualism, because of the reference to architectural theory.

“Swamp City Lament” by Alexandra Duncan is set in an alternate near-future where climate change has destroyed civilisation as we know it. Duncan’s world-building is effective enough to almost make the reader feel that this is a secondary world setting. The main character is a girl called Miren who resents that her mother has given up the role of concubine to become the queen of the Swamp City, presumably because of the lack of attention she feels she will receive in the future. There is also a baby on the way. Her friend, a boy by the name of Belly, has spotted something green growing out of a swampy street. It is the first plant the children have ever seen. Duncan succeeds in her aim of portraying the growing pains of a young girl and also of humanity struggling to survive in a world ruined by environmental catastrophe.

The narrative of “Death Must Die” by Albert E. Cowdrey makes use of what I felt was an unnecessary framing device, posing as a learned article in The Journal of Spirituality and Paranormal Studies. I can’t really see why, it really adds little to the story about the ghost of a hangman haunting the house he used to live in. The ghost has been dormant for a while but has revived himself to scare the new tenant of his former home, who is a lawyer representing an anti-death penalty group. The story is from the first person perspective of the Psychic Investigator (P.I.) employed to rid the lawyer’s house of its ghost. I found the story and the means that the P.I. uses to banish the ghost to be too predictable. The title is quite clever, yet I found the story itself a disappointment.

“The Exterminator’s Want Ad” by Bruce Sterling is a more full-blooded first person narrative, which doesn’t follow the pattern of a predictable narrative at all, but still tells a great story. Like several other pieces from this issue, it is set in a dystopian near-future ruined by climate change. The survivors of this near-future are socialist, social networking do-gooders, who insist that everything is shared, nothing is private or privatised. The story’s anti-hero is hated by and hates this regime. He used to make money from hacking social networks and file-sharers, but was imprisoned for his crimes. He confesses that he’s a nogoodnik and he adopts Sartre’s adage that “hell is other people.” I loved this story for its style and characterisation; the language used by the main character works perfectly, for instance. The story also works well as a satire of both sides of the file-sharing, social-network debate.

With “Crumbs” by Michaela Roessner we turn to fairy-tale horror set in the present day. We’ve seen vampires, werewolves and other paranormal creatures given new life in a contemporary setting, but this story uses a well-known fairy tale and neatly turns it on its head to give it new life in a modern setting. Roessner has also certainly done her research on making gingerbread. A well told tale with a great deal of atmosphere and suspense in the mix.

“Venues” by Richard Bowes is set in a contemporary US and begins with the protagonist, a speculative fiction writer, competing for PR coverage with others at an Arts Zoo, meant to give publicity to the plights of poor artists denied air time in the media. The rest of the story follows this writer around a number of live reading venues, where he is haunted by the ghosts of speculative writers of the past. The writing is good and the characters are interesting. The idea of the Arts Zoo struck me as original, but I was disappointed that this was not developed further. I found the descriptions of live-readings interesting and amusing but overall I didn’t feel the theme of old writers haunting current writers was taken as far as it could have been.

“Planning Ahead” by Jerry Oltion warns the reader of what can happen if you don’t have stocks of basic provisions in your home. Nathan has invited Frieda back to his home for a drink and is hopeful of going all the way, but things start to go wrong when he has to visit the local convenience store because he’s run out of something vital to consummate their passion. This event changes Nathan’s attitudes to provisioning forever, so that for the rest of his life he becomes a hoarder, systematically stocking his house and never throwing anything away. I liked the simple but powerful idea behind the narrative, and I think there is also a message in there about how we should deal with a world in which even rich countries like the US may experience shortages. Again, this story is set in a near-future world where environmental problems lead to a downgrading of our current affluent lifestyles. I did feel though that this story would have worked very well without projecting the story into the future, so I wonder if it can really be considered as science fiction. I liked the story nonetheless for that.

“Free Elections: A Mad Amos Malone Story” by Alan Dean Foster is a new story in Foster’s series about a mountain man of the 19th century American West called Mad Amos Malone. This was my first experience with Mad Amos, and although I liked his character and especially his horse (which is a unicorn rather than a horse), the story didn’t work for me. Mad Amos arrives in a town that is suffering from water shortages because an old man has decided to sit on top of the spring that provides the town with water. The old man can’t be budged by anyone and won’t move unless he’s paid a large ransom. Mad Amos takes on the challenge to move the old man and return water to the town.

The outcome is predictable, although of course the reader can’t predict how Mad Amos will solve the problem, and there is some interest in that aspect of the plot. But I never really felt that much engagement with the characters. Mad Amos seemed confident that he would prevail and the townspeople were never really suffering so much that you felt concerned for their plight.

The protagonist of “Ware of the Worlds” by Michael Alexander feels that life without anyone else around would be much more peaceful. He’s a loner who lives miles from the nearest town and would love to be self-sufficient. When capsules that have fallen from space bring the ability for their users to replicate anything they want, it seems that his dream has come true. But for the rest of the world (the capsules land in lots of places), the capsules are a disaster. Somebody wishes for the wrong things and society collapses. It’s interesting that in this story mankind brings on its own problems, but in a rather more unusual way (i.e. not by ruining the environment for once).

John Kessel wrote “The Closet” for a Festschrift to commemorate Ursula Le Guin’s birthday. So you would expect this story to discuss themes prevalent in Le Guin’s fiction. It’s no surprise then that the story deals with a misogynistic central character. This guy is a perfect example of the type. He doesn’t even care if he knocks over prams when he’s cycling past, and all he looks for in a woman is a one night stand with no strings. There is a big twist at the end of the story so I can’t really say much more about the plot, but I can say that I enjoyed this short and neatly constructed story.

I thought that “Teen Love Science Club” by Terry Bisson was the most original story in this issue of F&SF. Bisson provides a mix of high school angst and black holes. The school’s science club decides to build a black hole, but then their teacher and other pupils begin disappearing. Most of the other stories in this issue could easily work as mainstream stories without a speculative element, while Bisson succeeds in combining science fiction, interesting characters (enough for a short story anyway), and a well constructed narrative with his usual dash of humour.

There’s some good writing in many of these stories. But are they fantasy, are they science fiction? I guess so, sort of, if that means a story is fantasy or science fiction if it has a ghost in it or something dropping out of the sky from space. I don’t want to get hung-up on the category thing, but if a magazine is to be a forum for the best in fantasy and science fiction writing, it does feel like the speculative element of many of these stories isn’t providing the main inspirational spark for their creators. The ideas are there for characters and situations, but the speculative element often seems tacked on, or to be used as a convenient plot device, rather than central to the story’s soul.