Asimov’s, November/December 2021

Asimov’s, November/December 2021

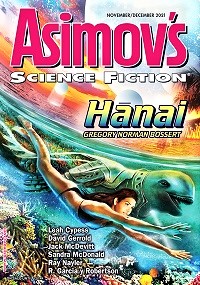

“Hānai” by Gregory Norman Bossert

“Muallim” by Ray Nayler

“And the Raucous Depths Abide” by Sam Schreiber

“Dream Interpretation” by Jack Skillingstead

“The Gem of Newfoundland” by Sandra McDonald

“Striding the Blast” by Gregory Feeley

“Czerny at Midnight” by Sheila Finch

“From the Fire” by Leah Cypess

“Bread and Circuits” by Misha Lenau

“Daydream Believer” by R. Garcia y Robertson

“The Ones Who Walk Away from the Ones Who Walk Away” by David Gerrold

“Tau Ceti Said What?” by Jack McDevitt

“La Terrienne” by John Richard Trtek

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

Thirteen new stories take readers to various places on Earth, real and imaginary, as well as the depths of interplanetary and interstellar space.

“Hānai” by Gregory Norman Bossert is set in the independent nation of Hawaii at a time in the future when several aliens have contacted Earth. The protagonist is an anthropologist, disgraced when she performed what she believed to be a moral duty while examining an extraterrestrial fresco. The last surviving member of an alien species comes to Earth in order to perform a final dance with her, blending its own traditions with those of hula. Their collaboration draws the cryptic, and possibly hostile, attention of other aliens, as well as that of human organizations. The performance leads to a strange transformation.

The author manages to create a complex background that is never confusing. The characters, human or alien, are richly developed. Hawaiian culture is depicted in a vivid and convincing manner. The presence of alien starships with unknown motivations adds a true sense of wonder.

We travel halfway around the world to a mountain village in Azerbaijan in “Muallim” by Ray Nayler. The title character is a robot teacher, sent to the remote community by the government in an effort to improve education. The project is less than effective, due to the very small number of children in school, as well as a lack of technical support. Some of the villagers are hostile to the machine, going so far as to attack it. The robot seems doomed to failure and destruction, but there are other ways it can be useful.

The author is obviously quite familiar with the setting and its inhabitants, making the story seem very real. Without being overly anthropomorphized, the robot becomes a sympathetic character. The upbeat conclusion is both plausible and unexpected.

We turn from land to the deepest part of the ocean in “And the Raucous Depths Abide” by Sam Schreiber. In the remote past, an alien probe is sent to Venus in order to observe life on Earth from a distance. Due to a malfunction, the vessel lands in Earth’s ocean instead. The ship’s artificial intelligence is split into two parts. After an immense length of time, the two AI’s contact each other, with different ideas about how to conceal their presence from Earthlings. Their conflict has profound implications for humanity.

This story is written in the style of a nonfiction essay, giving it a dry, distancing effect. (The plot is based on the so-called Bloop, the loudest underwater sound ever recorded, which remained a mystery for several years.) Although the premise is interesting, many readers are likely to find it more intellectually appealing than emotionally involving.

In “Dream Interpretation” by Jack Skillingstead, a psychiatrist’s patient claims that an alien artifact has altered probability, and that what seem to be only dreams are actually perceptions , a version of the real universe. The psychiatrist dreams of another life, leading him to suspect that her story is true. An apocalyptic event confirms this bizarre notion, and changes the psychiatrist’s life.

The plot changes mood often, from introspective to world-shaking, and then back to intimate again. The story combines a “what is reality” theme, in the tradition of Philip K. Dick, with aliens, mass violence, and a love story. These disparate pieces do not always fit together well.

“The Gem of Newfoundland” by Sandra McDonald takes place in a version of the modern world in which mermaids are real. The narrator inherits her grandmother’s house, which happens to include an old, chain-smoking, cantankerous mermaid in a tank in the basement. An elderly man becomes obsessed with the creature, leading to a sudden change in the situation.

The author deserves credit for creating a mermaid who is unattractive and obnoxious, rather than the beautiful and alluring being from legend. Despite the fantasy content, the most important part of the plot is the narrator’s growing awareness of her drinking problem. This may seem jarring to many readers, given the quirky, tongue-in-cheek mood of the rest of the story.

We leave Earth for the planet Mercury (called Hermes in the story) in “Striding the Blast” by Gregory Feeley. In the far future, greatly enhanced human beings race across the surface of the planet, flying in the thin atmosphere that was artificially added to it. The protagonist is punished for a theft by being forced to join in this flying contest, with the expectation that she will crash and die. Instead, she is rescued by a strange group of underground beings, partly organic and partly mechanical, who were discarded when more advanced servants replaced them. With their help, she plans a way to ensure that their progeny will survive, as well as working on a scheme of her own.

If this synopsis is not completely accurate, that may be because the plot is difficult to follow. The author shows great imagination in creating an exotic setting, full of unfamiliar concepts. (Although the story is pure science fiction, it has the otherworldly feeling of sword-and-sorcery.) The ending comes very suddenly, leaving the reader unsatisfied.

We return to Hawaii in “Czerny at Midnight” by Sheila Finch, a sequel to a previous story about a scientist trying to communicate with octopi. In this tale, her gender-fluid, possibly autistic, young child is able to make a connection with an octopus through music, in a way that is not clear. An artificial intelligence offers insight into the situation.

The introductory blurb makes it clear that the author is working on another story in this series, which may explain why this tale does not seem complete. The observations made by the AI at the end are likely to strike many readers as overly mystical.

The narrator of “From the Fire” by Leah Cypess is an art expert who formerly went back in time to study the works of a Renaissance master. She has lost her position as a time traveler because she questions the standard belief that the past cannot be changed. A wealthy man contacts her, asking her to determine if a painting he owns is an authentic work, rescued from destruction during a trip back in time.

The author appears to be familiar with Venice at the time of Botticelli and Savonarola, and flashbacks to the narrator’s trips to this era are the highlight of the story. The logic of the premise is questionable. It seems to me that whether or not time travel changes the past would have been proved one way or the other long before the protagonist’s adventures.

In “Bread and Circuits” by Misha Lenau, household devices equipped with artificial intelligence sometimes acquire full sentience and are discarded by their owners. The narrator adopts these machines, caring for them as best as possible. A baking machine shows up, and the narrator develops a close relationship with the lonely appliance.

The whimsical premise may remind one of “The Brave Little Toaster” by Thomas M. Disch and the animated film adapted from it. The human and mechanical characters are likable, and the narrator’s struggle with fibromyalgia adds poignancy. The author walks a very thin line between honest emotion and sentimentality, and at times the story strikes one as a little too cute.

We leave Earth for the far reaches of the Solar System in “Daydream Believer” by R. Garcia y Robertson. A teenage girl works on a help line on a colony ship bound for Saturn. She becomes deeply involved in a space war, leading to adventures both in the real world and virtual reality.

This brief synopsis offers only a hint of the story’s complicated and somewhat confusing plot. The space war involves multiple factions, and it is not always clear who is fighting whom. The connections among dreams, virtual reality, and the real world are unclear as well. Certain events that seem to violate the rules of this universe are left unexplained, dismissed by the characters as magic. Readers may be swept away by this fast-moving space opera, which is likely to appeal best to young adults.

The title of “The Ones Who Walk Away from the Ones Who Walk Away” by David Gerrold makes it clear that the story is a direct response to Ursula K. LeGuin’s famous tale “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” Explorers reach the uninhabited ruins of a city much like the utopian one in LeGuin’s story, and learn of its fate.

The author questions the idea that walking away from a prosperous city that depends on the suffering of others (a single child in LeGuin’s version, an entire underclass of abused workers in Gerrold’s) is a sufficient response. The story offers much food for thought, even if it lacks the elegance of LeGuin’s moral parable.

In “Tau Ceti Said What?” by Jack McDevitt, an interstellar probe carrying an artificial intelligence discovers two planets with sentient inhabitants orbiting the star mentioned in the title. Some of the messages sent back from Tau Ceti are undecipherable. The solution to the mystery suggests what might happen to Earth in the future.

This brief cautionary tale is clever and written in a clear, engaging style. Some readers may find that it appeals to the mind more than the heart.

“La Terrienne” by John Richard Trtek is this issue’s only novella. The main character is the sole human being on a distant planet, working for one group of aliens who compete with others. He sees what seems to be a human woman. She turns out to be an alien who has been given false memories of her life on Earth. The protagonist soon encounters the real human woman who served as a model for the imitation and becomes involved in a web of deception.

As the introductory blurb suggests, this tale of adventure on an exotic alien world has the flavor of a story by Jack Vance. Vancean elements seen here are a roguish hero, whose duties include theft from competing aliens; plots and counterplots; detailed descriptions of alien cultures; and a calm, often decadent mood, even when violence is involved. The author’s worldbuilding is admirable; however, like many a story by Vance, the narrative style has a sardonic, cynical tone that not all readers may enjoy.

Victoria Silverwolf has not been to Hawaii.