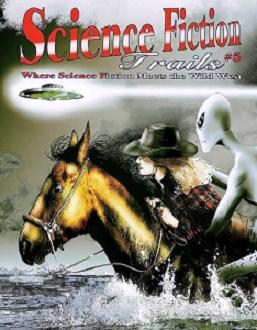

Science Fiction Trails #5--2010

(annual)

“A Djinn for General Houston” by Lou Antonelli

“The Gunslinger’s Code” by David M. Fitzpatrick

“Wildness” by John M. Whalen

“Grasshoppers” by John Howard

“A Sackful of Morgans” by C. J. Killmer

“Cowboy Jake and the Moon Men” by Jennifer Campbell-Hicks

“High Noon of the Living Dead” by Sam Kepfield

“A Thousand Deaths” by Jack London

Reviewed by Steve Fahnestalk

It must be hard to find SF Westerns, as two of the eight stories in this volume are reprints; the first from 2006 (“A Djinn for General Houston”), and the other from 1889 (“A Thousand Deaths”), although there’s a good fantasy Western in issue #18 of Orson Scott Card’s Intergalactic Medicine Show.

The first reprint, by Lou Antonelli, is arguably the best story in the issue, but we don’t review reprints, so I’ll just say this concerns a “magic lamp” from the future, General Santa Anna, and a decidedly different “djinn” from the usual. (It’s really science, not magic, but remember Clarke’s Law: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”)

The next one, “The Gunslinger’s Code” by David M. Fitzpatrick, is about a bounty hunter who’s hired to kill a notorious outlaw for a higher price than the bounty that’s already on the outlaw’s head. Mr. Wilmington is the gunslinger who’s been hired by a Mr. Varley to shoot Two-Face McAllister, because the latter killed Varley’s son. Seems McAllister was robbing a train, and Varley the younger tried to be a hero.

So far just sounds like a Western, right? And a clichéd one at that, but Fitzpatrick has a surprise in store; Wilmington finds out that McAllister is a human from another planet. Because of his “code of honor,” McAllister doesn’t kill Wilmington, instead taking him on as an apprentice, teaching him all he knows, and even granting him nano-augmentation. So it’s a bit less clichéd than it sounds, but in another way it falls a little flat, because there’s too many ideas packed into a short story, in my opinion.

Fitzpatrick can write, there’s no doubt, but I’m not sure the SF Western is his milieu—and while it sounds like I’m damning the story with faint praise, I actually enjoyed it, even sure as I am that it probably won’t make any best-of-year anthologies. Recommended with reservations.

“Wildness” by John M. Whalen, on the other hand, is not good from the very first sentence, which begins “LX-47 slid the Personal Transport Unit (PTU) in for a smooth landing…”—which would have been clunky and clumsy even for a straight SF story. I’m not sure even Lionel Fanthorpe would have used this opening. Unfortunately for the reader, it gets worse.

Alex Forty-seven, as he comes to be called, has a “laser gun” which “spacks” red rays and either explodes things or burns or slices them up, depending on how the author feels, I guess—and Alex allows himself to be disarmed by a man holding a revolver. I don’t know about you, but I think I’d probably be able to “spack” the hell out of a guy holding a revolver if I had a working laser gun. Even if that man was Wyatt Earp. Yep, we meet the Earps, Doc Holliday and even Ike Clanton.

Unfortunately for this story and the reader, it’s amateurish in every way. The old idea of giving aliens alphanumerical designations went out in the forties, I think—and why would they use our alphabet or numerical system? And no surprise that the alien that LX-47 is hunting turns out to be Doc Holliday, or that LX violates his “prime directive” a la James Tiberius Kirk. Avoid this story.

“Grasshoppers” by John Howard is a “politically correct” story, but there’s nothing wrong with it for all that. Amos is a Buffalo Soldier—since there’s no real time-frame given in this story, we can assume it was after 1866, when most African-American regiments were called that. He’s the sergeant in charge of a detachment of troops (their officer rode off fearing for his life) who are assisting a Berkeley (California) professor who has invented a self-guiding (“grasshopper”) artillery shell under the auspices of the War Department.

Professor Burnham has as little regard for the soldiers as they have for him; he had assumed the missing Captain was the owner of these men, not being familiar with Army protocol. We soon learn he has as little regard for the nearby peaceful Piutes as he had for the African-American soldiers, and in short order the professor gets his comeuppance. Short, wry and pithy.

“A Sackful of Morgans” by C. J. Killmer concerns one “Lefty” Bolingbroke, late a soldier of the Confederacy, who is approached one night by a Whitaker Myers and asked to take part in a field test of a new invention. Myers is pretty sure that this invention will, with Bolingbroke’s endorsement, make his reputation as an inventor—and he offers him a sackful of brand-new-minted Morgan dollars as incentive. (The Morgan dollar is named after its designer, and features the head of Liberty on one side and a bald eagle on the other.)

He also offers Bolingbroke thirty percent of the profit, and has an idea of how to test his new invention, which just happens to be a brain-powered artificial arm, to replace the right arm Bolingbroke lost in The War: Bolingbroke will practice with this new arm and then pick a fight in a poker game. Bolingbroke duly practices with the new arm and becomes proficient in drawing and shooting in a relatively short time.

But what promises to be a profitable walk in the park turns out to be a thorny road in some ways, and both Bolingbroke and Myers are in for a couple of surprises. Well researched, cleverly written, and engaging. You’ll probably enjoy this quite a bit.

“Cowboy Jake and the Moon Men” by Jennifer Campbell-Hicks is the first story to feature the well-known “grays”—the familiar alien with the almond eyes and the big bald head. They’re called Moon Men and they mostly talk only to the buffalo and occasionally to the Indians.

Jake Longstreet lives in Colorado and loves being your stereotypical Western guy who drinks in the saloon, rides a horse on cattle drives, and has a gal named Shyann. Well, she’s not really “his” gal, but of all the men who patronize the saloon, she likes Jake the best, because he doesn’t “treat her like a whore.”

One fine afternoon, Jake comes into the saloon looking to get drunk and spend his cattle drive pay at the poker table, when he gets (through no intention of his own) involved in a fight between Shyann and Benjamin Davis, a buffalo hunter who wants Shyann for his very own. Again, without meaning to, Jake gets called out for a gunfight by Davis, who considers himself a bit of a badman.

What happens to Jake, Davis and Shyann, and how the Moon Men come into this story you’ll have to pick up the magazine to read. Not as much period information as in Killmer’s story, but a fun read.

“High Noon of the Living Dead” by Sam Kepfield is an odd story to find in an SF/Western magazine, because it’s got zombies in it. You’d think zombies would have more to do with black magic than SF, but Kepfield manages to bring in a sort of scientific justification for their presence in Dodge City in 1875.

Elijah Stewart, a teacher of biology and chemistry at Kansas State Agricultural College is doing field research with his assistant, one Kathleen Halloran; they head into Dodge just in time to meet what used to be Joe Floyd and his cattle drovers, who had unwisely taken Junius, a large black man from the Caribbean on as cook.

As opposed to almost everyone in the Resident Evil movies, Stewart and Halloran quickly learn that to put one of the Undead down, you gotta shoot ‘em in the head. It turns out that Junius is in the employ of one Jean-Louis Henri Lefebvre, ex-Confederate general, who plans to set up his own secessionist South by feeding the populace treated beef that will sap their wills and leave them subject only to his.

In the process of solving this, we meet Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday; these ones, though, are more convincing than the ones we met briefly in the Whalen story. Another fine blend of SF and Western, with an interesting and satisfying conclusion.

Finally, the Jack London reprint, “A Thousand Deaths,” is an oddity about a long-suffering son with a scientifically-minded father who doesn’t mind if his son perishes in the course of an experiment. Or many times, for that matter. I’m not sure it really works, but hey—it’s Jack London!

Trying to meld SF and traditional Westerns can result in either a Frankenstein’s monster of a story, where all the stitches show, or a smooth melding of both genres—entirely dependent upon the skill of the writer. As this magazine shows, you can get both; and since the SF Western is not that common a beast, sometimes the editor and reader have to settle for both.