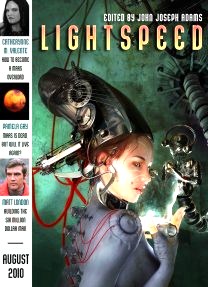

Lightspeed Magazine #3

August 2010

“Patient Zero” by Tananarive Due

“Arvies” by Adam-Troy Castro

Reviewed by Frank Dutkiewicz

“Patient Zero” by Tananarive Due is the tale of a ten-year-old boy named Jay. The lad is the survivor of a deadly virus that has claimed the lives of his family and every other living person who has contracted it. Jay is in the care of the CDC. For the last four years he has lived in a spacious plastic enclosure. The adults adore young Jay and do all they can to keep him sane and happy, even when the world outside is falling apart.

The story opens with a special moment for Jay, the moment being the first pages of a journal his teacher, Ms Manigat, convinces him to write, a request he finds odd. Jay is as happy as a child stuck in his predicament can be. He has become used to being poked and prodded. Saddled with an unstoppable disease, death has become a part of his life. He is cooperative and accepting with what his caretakers tell him, even when he knows it is a lie.

At first glance “Patient Zero” looks like another ‘boy-in-the-bubble’ tale. It is told from the pages of Jay’s journal, hardly a unique way to present such a piece. However, Ms. Due managed to turn a ‘been-there, read-that’ concept into an engaging work of art. The story is presented as if the reader finds an open journal in a strange place and uses it to decipher the clues of what has taken place.

Jay is shown as a boy who trusts the adults who care for him. They are protective of the boy, and appear to see him as their only hope, even when all hope is fading away. They shield him from news of the world outside, but can’t contain hints of civilization’s demise out of his tightly quarantined net. Jay is successfully portrayed as a child who has endured the worst of what any rational person can bear, even when it’s clear to the reader that he has been spared the worst.

As brilliantly as Ms. Due’s main character is written, the adults in the story are her true piece-de-résistance. They come across like stressed parents who still smile for their children even when life is crumbling around them. Jay’s perceptions and fears are shaped by their carefully guarded reactions. It is clear they are doing all they can to hold things together for their prisoner’s benefit.

As the dates of Jay’s journal progress, recollections of past incidents in the earlier days of his confinement surface. It becomes increasingly clear to the pampered and cared-for child that all is not right, but he reacts as any child would who has been told it will all be okay, by doing his best to ignore the clues of devastation. Masterfully done.

“Patient Zero” is an end-of-the-world tale told from a small island of tranquility whose shores are eroding from the rising tide of disaster. It may not be the best story I’ve read this year, but it is damn close.

“Arvies” by Adam-Troy Castro is a story of not one, but two people. Molly June is legally dead. A young woman of 15, she has been declared ready as a vessel, or arvies, for a passenger. Jennifer Axioma-Singh is the passenger. She is a first tri-mester fetus, and has been that way for 70 years. She has lived a full life and lived inside a variety of arvies hosts. Molly is her latest. Each arvies provides a unique experience, but with Molly, Jennifer wants to do something no ‘living’ person has ever considered. Give birth.

Adam-Troy Castro turns the term ‘Right to Life’ on his head with “Arvies.” He creates a future in which fetuses are symbiotic puppet masters who live inside genetically manipulated impregnated adults with hardwired and specially constructed wombs. Anyone born is declared dead and only the unborn fetuses are considered alive. When passengers like Jennifer become implanted inside an arvies womb, they assume control. The unborn use their impregnated hosts like expensive toys, switching between hosts when they tire of them. The ‘living’ treat their arvies as the wealthy of our age do luxury cars.

“Arvies” is an inventive idea. The story is a fresh take on symbiotic relationships, despite its air of familiarity (Dax of DS9 comes immediately to mind). Each ‘dead’ person is engineered to fit potential passengers. Imagine being inside a body-builder for a span of your life then switching into an elegant gymnast. Unborn fetuses like Jennifer live a very long ‘life’, while arvies like Molly are nothing more than vehicles that are destined for the scrap heap when used up. It was unclear to me how sentient ‘dead’ people are possible, but it is obvious that they are more than unfeeling cyborg machines. An intriguing concept, one that left me wondering how such a society could come about.

While I liked Mr Castro’s idea, I did not like the way he chose to tell it. “Arvies” was compiled into something that resembled a medical journal article but with a bedtime story narrative. Perhaps the author thought it would be best with the two very separate perspectives, but the experience left me disconnected and I had little sympathies for any of the characters because of it.

“Arvies” is good SF wasted on a dry narrative. It left me unsatisfied, but I was still glad to have read it.